New Delhi: The 4,000-year-old chariot would have been a showstopper at any history museum around the world. Not at the National Museum in New Delhi though.

Excavated in western Uttar Pradesh and hailed as a rare find that upended our way of scholarship about ancient India, the chariot was installed with little fanfare at the museum. No banners at the entrance or wayfinding signs to the big discovery. A poster above it had an uninspired title: “Ancient Indian Chariot”. The object that could have electrified the museum seemed dead on arrival.

In the Harappan gallery on the ground floor, the Sinauli chariot sits unassumingly behind a low barricade, the remains laid out in stainless steel cases with a couple of posters on the wall. Nothing suggested this was a paradigm-shifting discovery.

On 10 September, there were barely any visitors apart from a group of schoolchildren from Kanpur. They drifted past the chariot much as they did other artefacts, barely pausing to look. There have been no special guided tours to situate the big archaeological find in our current understanding.

And that is only one problem with the museum.

By and large, a crisis of imagination bedevils the National Museum. It is failing its own mandate “to disseminate knowledge about the significance of the objects” and to serve as a “cultural centre for enjoyment and interaction of the people”. Once Nehru’s vision of a “people’s museum” and an epitome of national identity, its treasures have often been overlooked because of how it fails to display, dramatise, and draw in the public.

The Modi government’s answer is Yuge Yugeen Bharat Museum in North and South Block, part of the Central Vista redevelopment. Developed with French expertise, it is pitched to be the world’s largest museum. If Nehru’s National Museum was meant for people, Modi’s is a civilisational showcase.

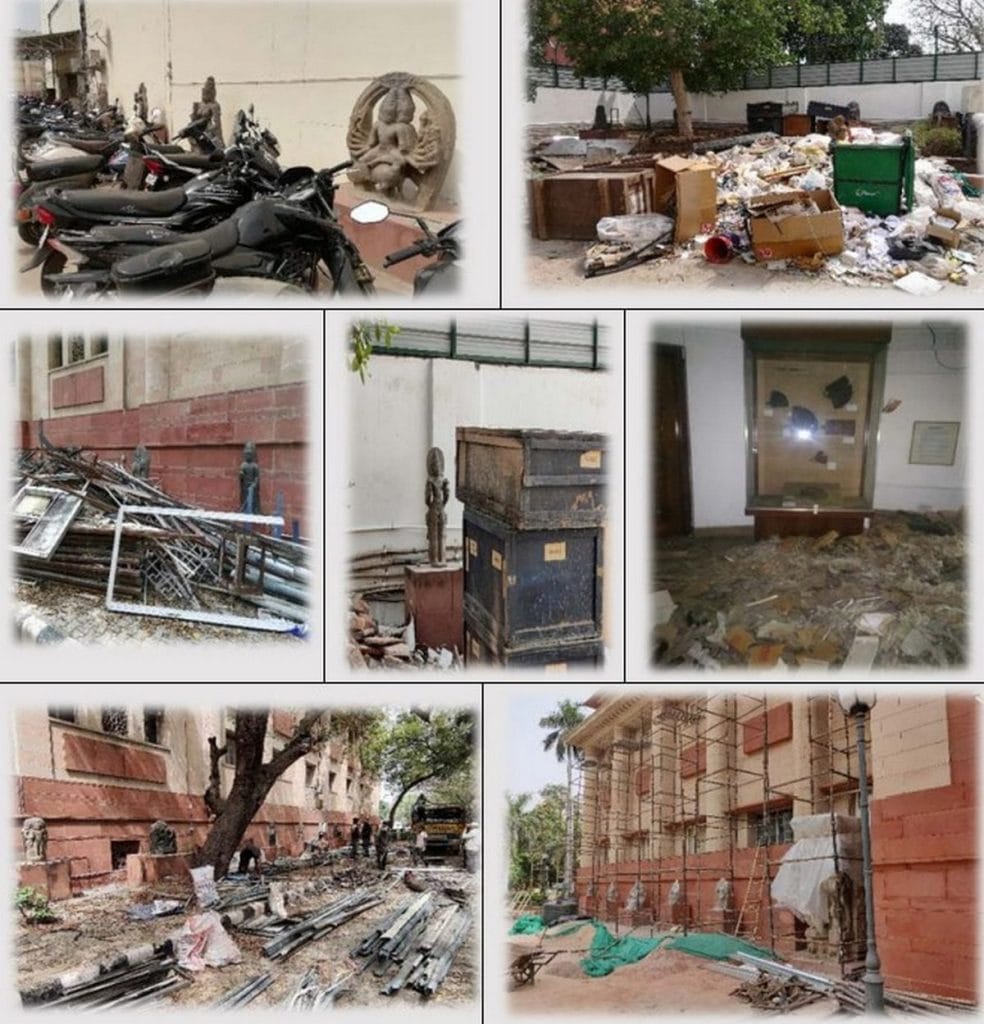

Yuge Yugeen has set off lamentations about the loss of the old National Museum. Yet the institution did not always do justice to its role as the custodian of India’s patrimony. For years, it has been marred by security lapses, bureaucratic sloth in ideas, inability to innovate, chronic delays in documentation and digitisation, poor curation, dull descriptions, complacence, and the closure of major galleries such as manuscripts and pre-history. There have been no concentrated efforts to fix this systemic decay. A shake-up was long overdue, whether or not one agrees with uprooting it to the Central Vista.

Indian museums are suffering from not having autonomy. Critical positions are vacant and run by poorly qualified people. Museums are vibrant cultural spaces which reinvent themselves to bring visitors. That’s no longer the case

-Venu Vasudevan, former director-general of the National Museum

A parliamentary standing committee on culture cited CAG reports from 2013 and 2022 that had noted physical verification of artefacts had not been done, making it more difficult to detect theft, and that digitisation was lagging. The 2023 report added that “over 90% of artefacts lay in the Reserve Collection without ever being on display.” Its advice to the Ministry of Culture to frequently rotate displays to “enhance the appeal of the museum” and ensure “artefacts are not forgotten or misplaced” went largely unheeded.

In 2023-2024, the National Museum got about 3.73 lakh visitors. By comparison, Kolkata’s Victoria Memorial drew over 36 lakh visitors that same year.

“The National Museum has been severely criticized for a long time and people never appreciated it,” said Naman Ahuja, art historian and professor at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). “It could not compete with other museums across the world. There were lapses and inadequacies such as inconsistency in presenting the chronology of the past, unattractive display, lack of specialist curation.”

India’s National Museum is a cherished and storied institution. But for the most part, the love is driven more by nostalgia than performance. As a premier institution, it failed to build a vibrant museum-going culture and community in India.

Also Read: Patna is now a city of museums. Making its history great again

A ‘museum nutcase’ and leadership in flux

For a brief spell in 2013, it seemed as if a metamorphosis was unfolding.

Closed galleries came back to life, a new garden café opened, LED bulbs were installed, the souvenir store was refurbished, and landmark exhibitions were mounted. It was all driven by the new director-general of the National Museum, 1990-batch IAS officer Venu Vasudevan. He proved a rare species — a civil servant with a passion for the arts, a self-professed “nutcase for museums”.

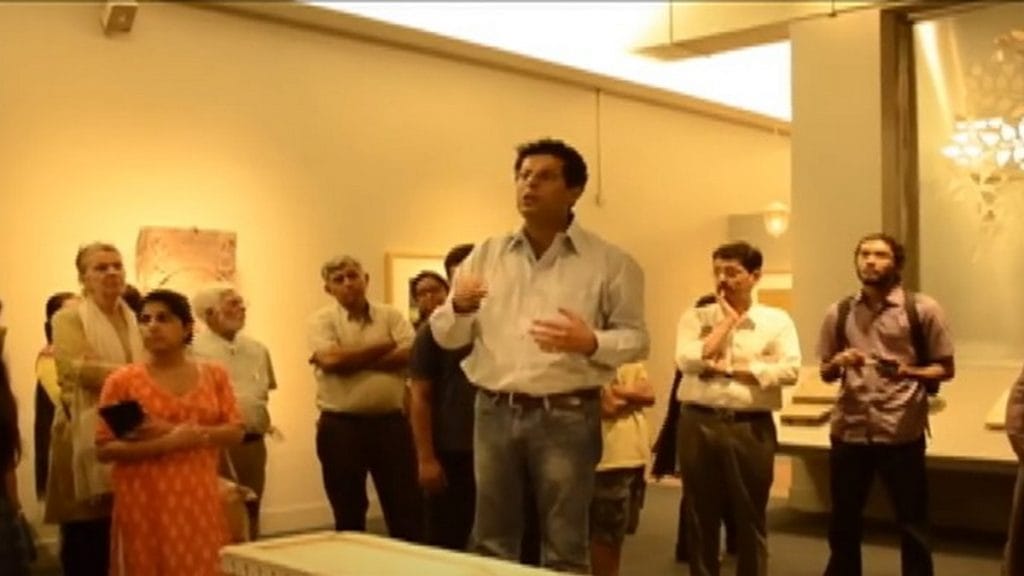

Among the high points were special exhibitions like Nauras, a visual telling of the ‘cosmopolitan world’ of the Deccani Sultanates, and The Body in Indian Art, curated by Naman Ahuja. The latter show, in 2014, brought together more than 200 works from 36 museums and private collections, spanning Chola bronzes from Tanjore, Mughal manuscripts and stone sculptures.

“I showcased the National Museum’s objects in a unique way, which had a different impact on the public,” recalled Ahuja. “That exhibition demonstrated that distinctive labelling and curation can be appealing.”

He claims around 1.5 lakh visitors came to see the exhibition and all the catalogues were sold out. “The current curation of the museum is not establishing the narrative of India’s past,” he added.

Earlier the best antiquities were sent to the National Museum collection. But now that has stopped. Purchase of artefacts also stopped for the last three decades

-Naman Ahuja, art historian

About midway through Vasudevan’s three-year term, he was abruptly transferred to the sports ministry. Upcoming exhibitions, including one on Parsi history, never materialised. The transfer triggered an online petition, with cultural figures including Ashok Vajpeyi, Romila Thapar, Gulzar and Girish Karnad opposing the move.

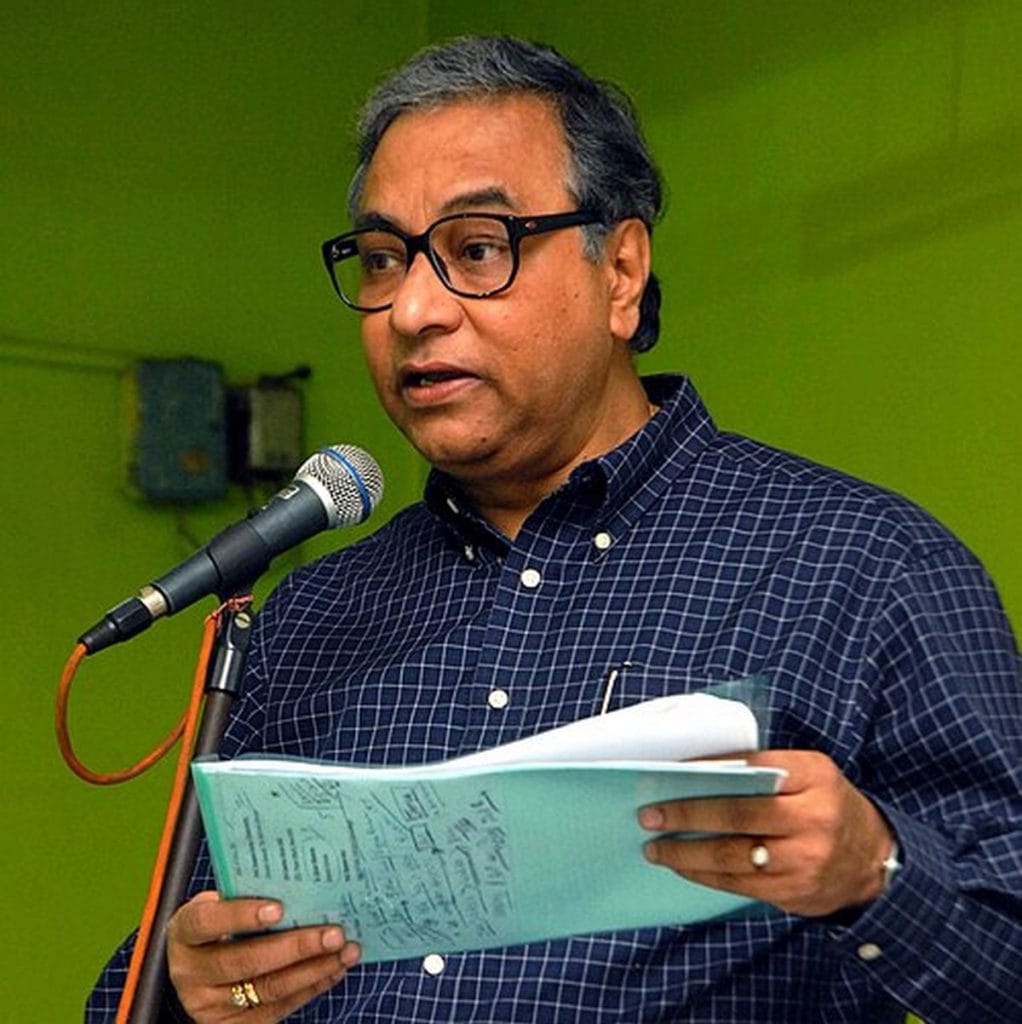

“Venu is perhaps the best DG that the National Museum has had after LP Sihare left some 25-30 years ago,” wrote former culture secretary Jawhar Sircar in 2015.

It was one of the most bemoaned moments in the museum’s chequered leadership. But since 1957, when its control shifted from the Director-General of Archaeology to the Ministry of Education and later to the Ministry of Culture, the National Museum has lived with instability at the top. And after Vasudevan’s exit, it became a veritable revolving door.

Archaeologist BR Mani succeeded Vasudevan in 2016, serving until 2019. After that, the Modi government abolished the DG’s post altogether, creating a new “Chief Executive Officer, Development of Museums and Cultural Spaces,” filled by a 1983-batch IAS officer.

Two years later, in 2021, the CEO role was scrapped and the DG restored. Since then, the charge has passed from Partha Sarthi Sen Sharma, an additional secretary in the Culture Ministry, to Mani again in 2023, then to IIS officer Ashish Goyal, before landing with joint secretary Gurmeet Singh Chawla in May this year. The post requires a master’s degree in museology, art history, or a related field but officials have had varying degrees of impact.

The café and shop, once symbols of Vasudevan’s revival, are today modest at best. Café Museo, tucked beside the Buddha Gallery, can seat only about 20 people. The shop nearby has half-empty shelves, with a few titles like Monuments of Assam and Mysteries of Love: Maratha Miniatures of the Rasamanjari along with merchandise such as tote bags.

On 26 September, UPSC aspirant Yogesh Kumar visited the National Museum for the first time.

“In my textbooks I have read about these artefacts, and I’m thrilled to see these things which define India’s past. But many things like the Rakhigarhi findings are still missing from them,” he said.

Special exhibitions are infrequent. Shunyata: Emptiness, curated by diplomat Abhay Kumar, ran in December 2024, followed by Pehchaan: Enduring Themes in Indian Textiles in January 2025 and Ambaran: The Historic Buddhist Citadel of J&K in April.

“There were good bureaucrats also and terrible ones also,” Sircar told ThePrint. What has been a common denominator across the decades is attempts at rejuvenation either marred by a truncated end or slow execution.

The outsider dream

It isn’t as if people failed to spot the problems. But the solutions evaded almost everyone.

Soon after he became culture secretary in late 2008, Jawhar Sircar drew up a 14-point agenda to shake up India’s museums. He wanted to modernise museum practices, set up international partnerships, and bring in talent from abroad. But red tape stalled everything despite some initial successes.

“I went around from museum to museum across India with experts and found what the pluses and minuses of museums were. We put together a 14-point agenda and it just became a ready reckoner. And so it remains today,” said Sircar, who was one of India’s longest serving culture secretaries, with his tenure ending in 2012.

Some initiatives got off to a promising start. Sircar forged the first formal cultural partnership between India and the UK. An agreement with the Art Institute of Chicago was signed to upgrade Indian museums and their human resources. Under it, Indian professionals went to Chicago for training, while seminars and workshops were held in Delhi. An advisory committee of the National Museum was also set up at the time under the noted art historian BN Goswami.

Despite salary hikes, [international museum professionals] refused to come because they said the rest of the team would not understand what they wanted. It was one of my greatest failures

-Jawhar Sircar, former culture secretary

But when it came to changing the National Museum’s leadership, Sircar’s efforts hit a wall. One of his most radical ideas was to open the DG’s post to foreign-trained scholars, even extending the age limit to make the position attractive. But the Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) refused, insisting the post could only go to an Indian official and rejecting any change to age limits. After three years of back-and-forth, the idea collapsed and the old system of bureaucrats remained in place.

“We fought with UPSC for years. They complained to PM Manmohan Singh that this secretary is not [following] our path,” he recounted.

Several experts abroad were contacted, but none were inspired enough to jump and come to a beleaguered institution.

“Despite salary hikes, they refused to come because they said the rest of the team would not understand what they wanted. It was one of my greatest failures,” said Sircar.

Venu Vasudevan tried to pick up the thread when he became DG of the National Museum.

“Sircar’s ideas were pathbreaking,” Vasudevan told ThePrint. “Within several constraints and challenges, I brought in expertise from outside in order to enrich the museum.”

That phase saw collaborations with foreign museums and experts, and a run of exhibitions that, as Vasudevan put it, “created an excitement about the National Museum.”

But the deeper malaise remained. A lack of room for innovation, initiative, and risk-taking.

“Good museums run on professional lines. Indian museums are suffering from not having autonomy. Also, museums don’t have the right resources to run. Critical positions are vacant and run by poorly qualified people. This is a recipe for disaster,” he said. “Museums are vibrant cultural spaces which reinvent themselves to bring visitors. That’s no longer the case.”

Ironically, the National Museum itself was founded on outside talent: its first director-general, Grace Morley, was an American.

‘A mirror to the national self’

The seeds of the National Museum were sown in an exhibition that flopped in London but triumphed in Delhi.

In the winter of 1947-48, the Royal Academy of Art staged The Arts of India and Pakistan, an exhibition with over 1,500 artefacts. For the first time, these were treated as fine art rather than curiosities from the East. But in the bitter aftermath of the Raj, the show failed to draw big crowds despite the huge inter-governmental effort. The art itself was dismissed by some critics.

“That the exhibition has been a failure has never been a surprise to me: it is a difficult art (in itself repugnant in many spheres to present-day tastes),” claimed the Victoria and Albert Museum director Leigh Ashton, comparing it unfavourably to Chinese and Persian art.

But as the noted late art historian Kavita Singh put it in her essay ‘The Museum is National’, this exhibition was “destined to have a far more significant afterlife in Delhi”.

Pandit Nehru was keen that there should be a museum that would be accessible to people from all walks of life

-Partha Mitter, art historian

When the objects returned to India, the Nehru government reinstalled them in the state rooms of the former Viceroy’s Palace—now Rashtrapati Bhavan—in 1949 and invited the public to the show, titled Masterpieces of Indian Art. On the throne platform where the viceroy once sat, the organisers placed a Gupta-era Buddha from Sarnath. The symbolism was unmissable.

“The exhibition in New Delhi was thronged with visitors. Its compression of five thousand years of Indian art was seen as a valuable mirror to the national self,” wrote Singh. “As the exhibition’s term drew to a close, even the prime minister felt that it would be a pity if the collection was dispersed. Accordingly, the Ministry of Education chose to retain this exhibition and make it the core of a new National Museum.”

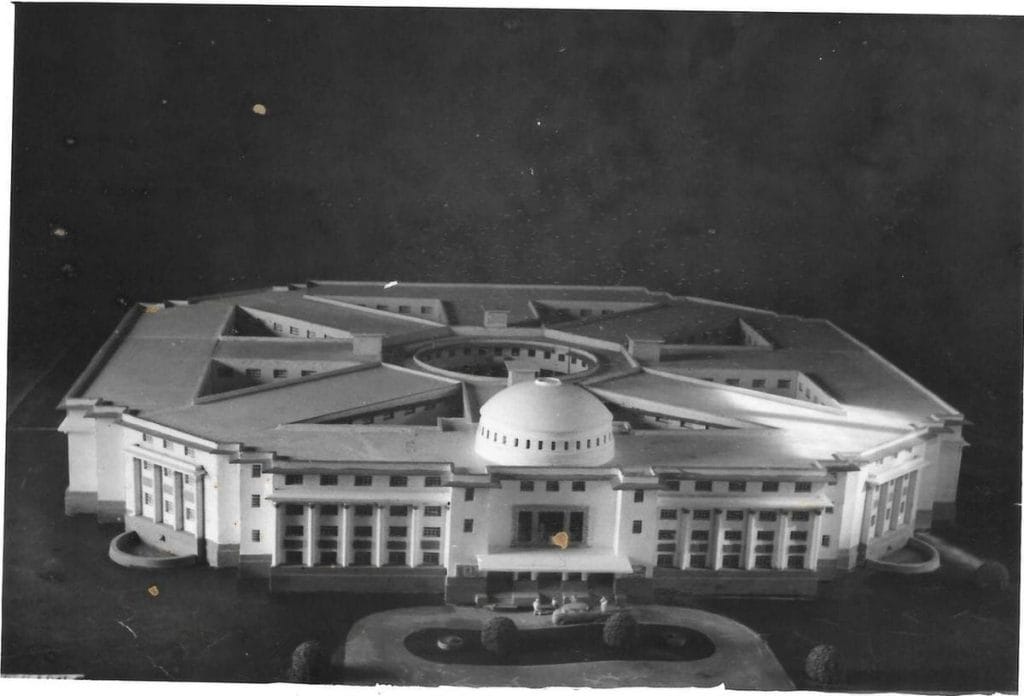

Thus conceived as a repository of Indian civilisation from prehistory to the present, the museum was established in Lutyens’ Delhi. Nehru laid its foundation stone in 1955 on the very spot where Edward Lutyens had once planned an Imperial Museum. The first phase opened in 1960, inaugurated by Vice President Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan.

The next step was to give it life. “Pandit Nehru was keen that there should be a museum that would be accessible to people from all walks of life,” said Partha Mitter, art historian and Emeritus Professor at the University of Sussex.

The pressing question was whether the museum should be run by an archaeologist, who knew the objects, or a museologist, who knew how to present them. Since no such professional existed in India, the government looked abroad. It found Grace Morley, the world-renowned American curator—the “foreign woman [who] set sail to make a national museum for India.”

The new building then consisted of an entrance hall, library, auditorium, and three floors of galleries. For the task ahead, Morley worked with a team that included Sanskrit and art scholar C Sivaramamurti, Smita Baxi as head of exhibitions, and Priyatosh Banerjee in charge of publications.

“My first task as the new director was to supervise the transfer of the material from the Rashtrapati Bhavan to the first unit of the new building and to arrange for its installation in the contemporary pattern of a museum intended for the instruction of the public as well as for its enjoyment,” Morley said in a 1982 interview. She’d just been awarded the Padma Bhushan, describing it not so much a personal honour as “a symbolic recognition of the museum profession and its importance in India today.”

A centre of learning

There was a grand mission in the air at the stately, sandstone National Museum in the 1960s, designed by the architect Ganesh Bikaji Deolalikar. Circulars went to schools and colleges, urging them to bring students. Daily gallery talks were launched. Morley was at the helm of it all.

“She shaped the National Museum as a centre of education. On her arrival in India she understood that the learning here was mostly bookish and the museums should make all efforts to provide the visual education to help all round development of the personality,” wrote Priyatosh Banerjee, former assistant superintendent, ASI who worked with Morley.

Her approach was unequivocal: a museum had to attract visitors. Banerjee noted that exhibits often came with “big descriptive labels, charts and diagrams” to help people understand the significance of what they were seeing. “She believed that a hospital and a museum should look like a mirror as they are important public institutions.”

In keeping with this vision, the National Museum Institute of History of Art, Conservation and Museology was established on the premises in 1989 to train a new generation of curators, conservators, and specialists. Over the years, it has produced several high-profile alumni, from Sonia Gandhi to noted theatre director Feisal Alkazi to Tina Ambani.

It’s very unfortunate that these days students are not interested in taking museum courses. Courses should be formulated in a way that matches the world standard of museology, including regular interaction with experts across the world

-Former vice-chancellor of the National Museum Institute

“The students from the institute became scholars and curators at various museums. It’s one of the prestigious institutes of the country,” said a senior faculty member.

Offering master’s and PhD programmes, along with short courses, it now operates from a new campus in Noida’s Sector 62, inaugurated in 2019 by then culture minister Mahesh Sharma. The facility includes an auditorium, laboratories, a library, classrooms, a seminar room, a hostel, and a guest house. In 2023-24, it added a Department of Palaeography, Epigraphy and Numismatics. However, only 10 students are enrolled in this department for the current academic year.

The 2022 CAG report noted poor enrolment in general at the National Museum Institute, with no PhD students admitted between 2013 and 2017. The government has since set up the Indian Institute of Heritage, meant to strengthen training and research in conservation.

“It’s very unfortunate that these days students are not interested in taking museum courses,” said a former vice-chancellor of the institute on condition of anonymity. “Courses should be formulated in a way that matches the world standard of museology, including regular interaction with experts across the world.”

Failure to evolve

Even as early as 1989, Om Prakash Agrawal, former head of conservation at the museum, warned that the institution was failing its mandate to educate and entertain. It simply did not speak to the wider public.

“Communication with the public has remained problematic,” he wrote. “People… may be more interested to know the story with which an art object is connected, or that it is depicting.”

These and other problems linger stubbornly. The National Museum struggles with everything from curation and staffing to infrastructure and visitor engagement.

“Earlier the best antiquities were sent to the National Museum collection. But now that too has stopped. Purchase of artefacts also stopped for the last three decades,” said Ahuja.

Former curator Tejpal Singh recalled how, until 1997, the museum would pitch a tent each February to buy antiquities. Art dealers and officials would haggle on site over prices.

“Since then, the art acquisition committee has been defunct and no antiquity has been purchased, ” Singh said. The museum’s collection has since grown only with gifts and repatriated objects returned to India since the Modi government came to power.

The stagnation has been flagged repeatedly — by the Vardarajan Committee in 2004, the Yechury Committee in 2011, and the CAG in its 2013 and 2022 audits.

Sending objects for the exhibitions is part of cultural diplomacy but in other countries museums don’t disturb the display gallery. But in India, we are removing objects from our display

-National Museum official

Meanwhile, the museum has not done much justice to the collection it already has. Out of more than 2.05 lakh artefacts, only 7,333, or 4 per cent, were on display in 2013, according to the CAG report, and no rotation policy was followed.

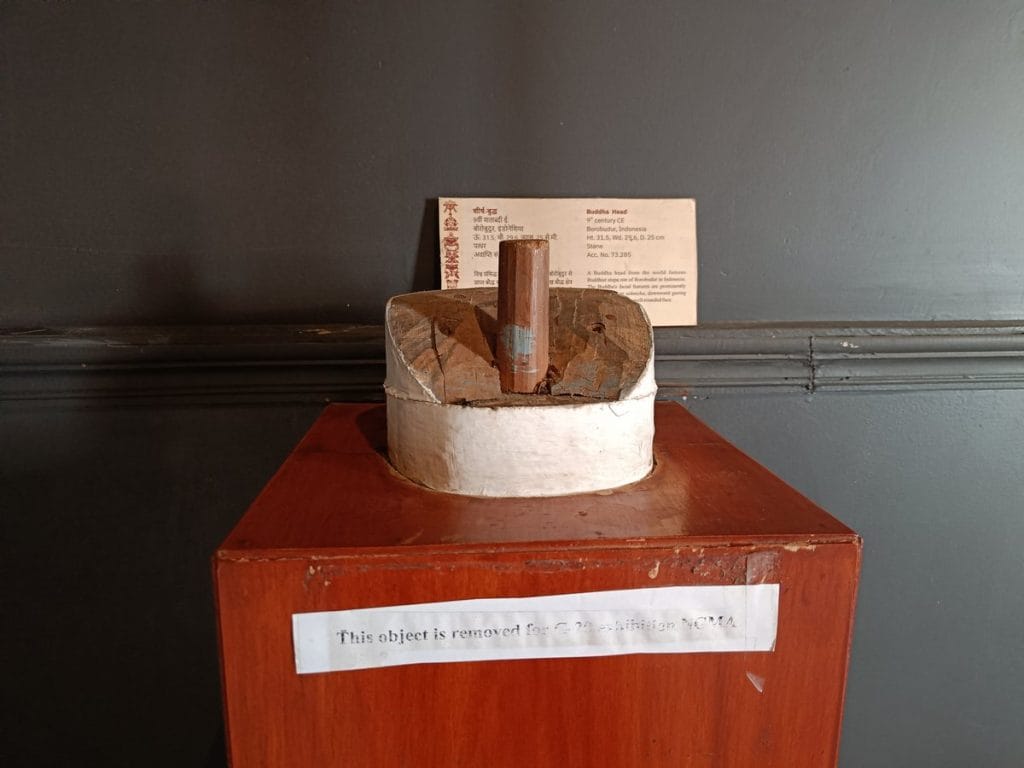

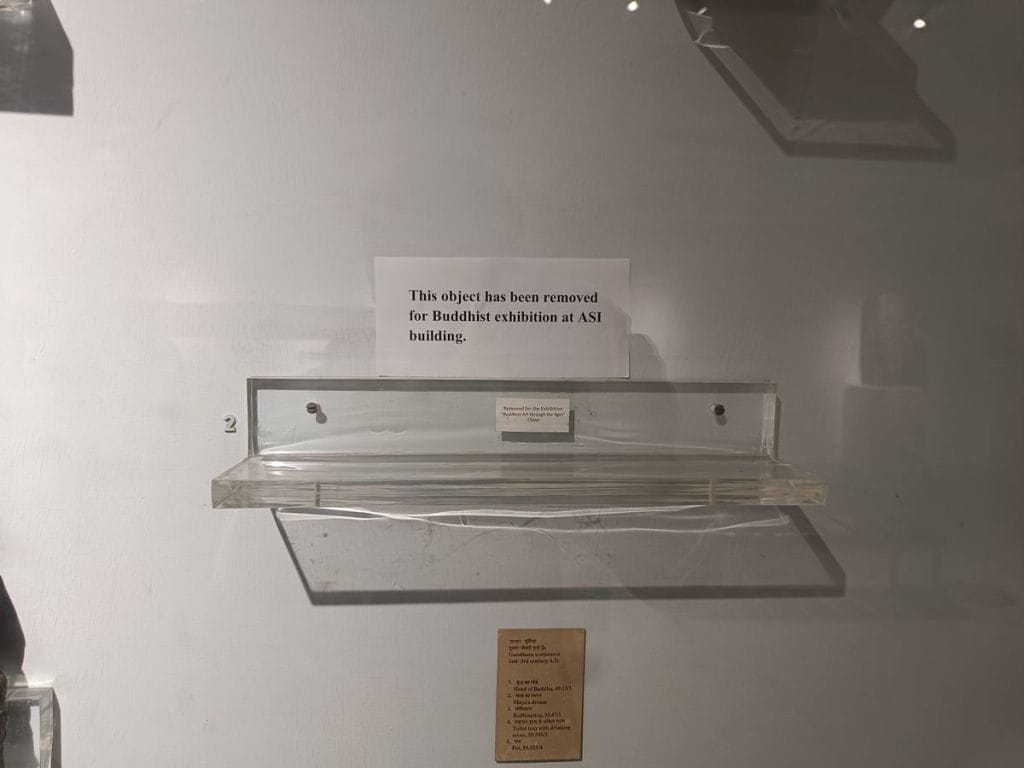

Worse, displayed objects were often removed for travelling exhibitions and not replaced for months.

At the Buddhist Gallery, for instance, a Gandhara sculpture, ‘Maya’s Dream’ (2nd-3rd century AD) was taken out for the show Buddhist Art through the Ages during the pandemic and has been in the ASI building ever since. A Buddha head from the 9th-10th century CE was sent out in 2023 and its place still lies vacant.

“Sending objects for the exhibitions is part of cultural diplomacy but in other countries museums don’t disturb the display gallery. But in India, we are removing objects from our display,” said an official of the National Museum.

Staff shortages compounded the neglect. The 2013 CAG audit found 122 of 276 sanctioned posts vacant. By 2022, the shortfall had improved but 36 positions were still unfilled.

“The National Museum is facing major functional challenges such as shortage of staff, specialists, and the need for expansion of the museum,” said former culture secretary Jawhar Sircar.

He argued that the institution was “top of the class” till about the 1990s, but then stagnated.

“What happened thereafter was, there was no technological upgradation other than say lighting and things like that. There was no expansion of the building,” he said. The Planning Commission had cleared expansion, but the neighbouring ASI office refused to shift. “There was no political will. The new buildings could not come up in the latest style of museum display.”

The museum could boast of grand artefacts, but did little to make them speak. Storytelling is largely missing. Text panels are often pasted like a book-on-the-wall. The galleries stand in silos and there is very little intersectional curation. Objects that were in storage largely remained there. Very rarely are the galleries reinforced with new artefacts and curations.

Temporary exhibitions are few and far between. There are four types: internally curated shows, collaborations within India, outgoing international exhibitions curated by foreigners, and incoming international exhibitions. An official of the National Museum said the institution manages only 5-10 such exhibitions annually.

“Posts were not being filled on time, and a lack of curators crunched the reputed institution. There is no justice with the collections,” said Sanjib Singh, a museologist who joined the National Museum in 1989 and worked there for more than two decades.

For instance, the Bronze Gallery was renovated in 2011 and the pieces were augmented with “Australian lights” and expanded captions. Yet the broader curatorial vision was still missing, with a jumbling of eras and regions, said Ahuja.

“In that case the gallery becomes the history of bronze. Similarly, there is no chronology in presenting the textiles,” he added.

Thefts, digitisation, and reforms

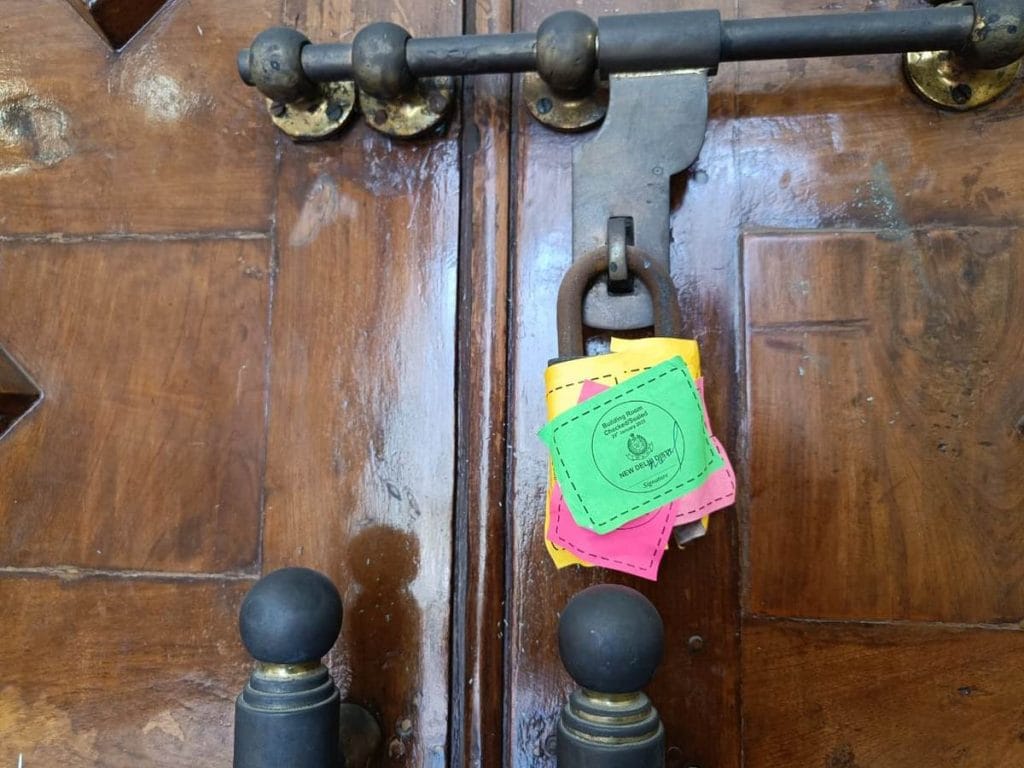

Without documentation and digitisation, even the most valuable collections are vulnerable. The National Museum has long faltered on this front.

The museum finally began systematic documentation in 2003, after 23 cases of theft were recorded in the previous two years. The job, though, is still unfinished despite some progress.

In 2014, the Ministry of Culture launched the Jatan digitisation project to create digital collections across Indian museums, including the National Museum.

According to the Jatan portal, about 1.05 lakh artefacts have been digitised so far, each with accession numbers, gallery names, material details and short descriptions.

One Harappan-period artefact, “Climbing Monkey,” carries this note: “This is the most realistic representation of a monkey who is shown climbing up a pole which he grips firmly with both hands and feet.”

But though such open-access catalogues were a much-needed reform, there’s much ground left to be covered.

The CAG’s 2022 report noted that the National Museum had digitised 1.73 lakh objects, but photography was complete for only 0.81 lakh of them as of January 2021. The Yechury Committee had also flagged the absence of physical verification, noting that some artefacts were missing or untraceable.

Theft has been a predictable consequence of this lackadaisical documentation.

The biggest heist came in 1968, when 125 pieces of antique jewellery and 32 rare gold coins disappeared.

“The total purchase value of the missing objects is about Rs 1,79,000. The theft was discovered on the morning of the 26th August, 1968,” Sher Singh, then minister of state in the education ministry, told Parliament.

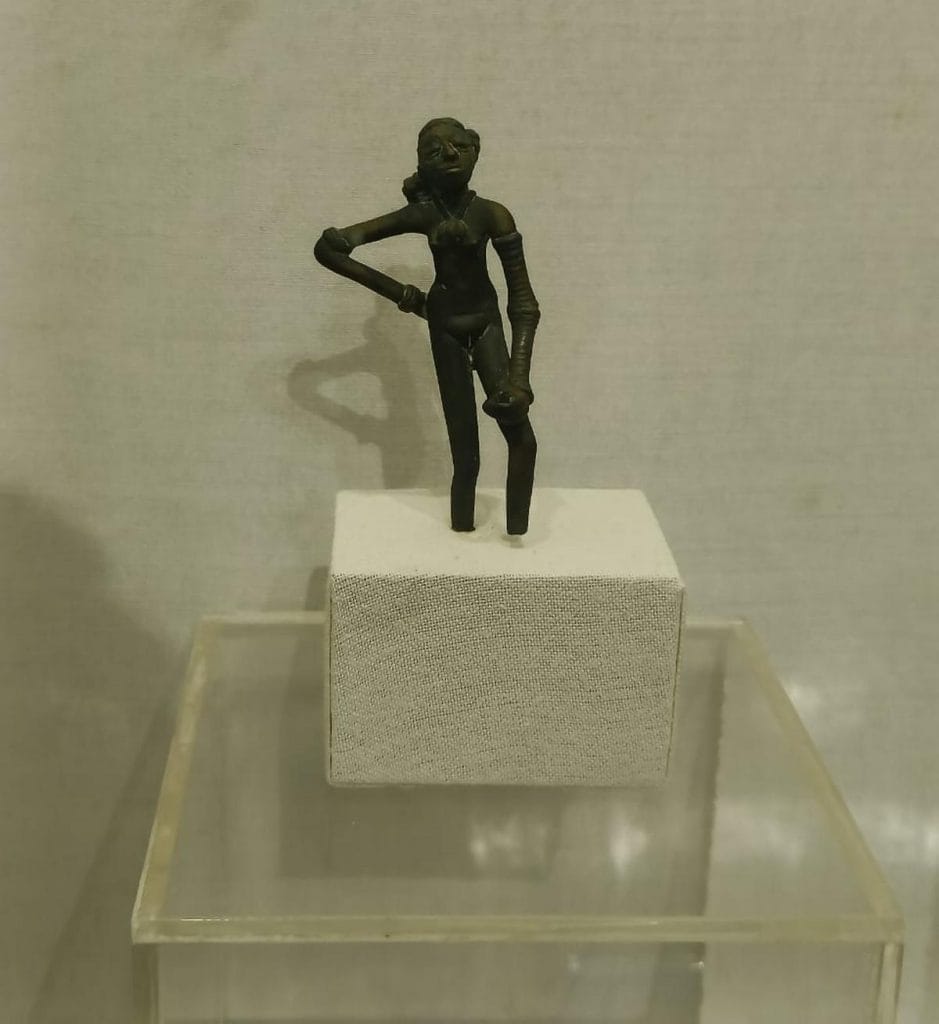

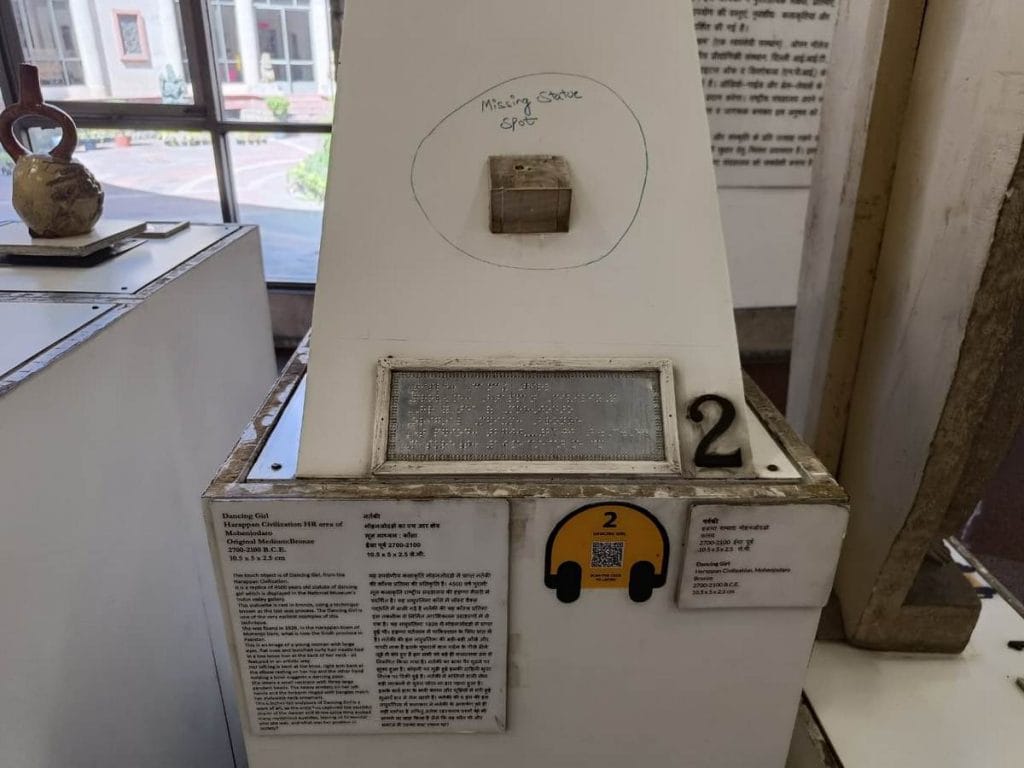

In 2018, the son of a retired Inspector General was caught on CCTV stealing an Olduvai handaxe; the object was later recovered. Most recently, the lifting of a replica of the Mohenjo Daro Dancing Girl—ostensibly by accident—once again underlined the fragility of security at the nation’s flagship museum.

At the Anubhav Gallery for disabled persons, where the replica was placed, there’s now a handwritten label: “missing statue spot.”

Different approaches

From the start, the National Museum has been shaped as much by its directors’ sensibilities as by its collections.

Grace Morley, its first head, approached it as a modernist project. For art historian Naman Ahuja, her tenure was about formal aesthetic pleasure: “Her focus was to present a beautiful exhibition. She didn’t want to get entangled with history, civilisation, and religion.”

Her successor, C. Sivaramamurti, brought a very different lens. With a “conspicuous vibhuti and tilak” on his forehead, he read Indian art through the country’s religious and literary traditions, framing civilisations in that context.

National Museum not only changed the nomenclature but also interpreted some artefacts in the gallery to establish that there was a Hindu theme in the beliefs and practices of the people of the Indus Valley civilization

-‘Musings on Museums’, IIC Quarterly (Summer 2010)

Then came the urbane LP Sihare, armed with a PhD at New York University. In his four tenures between 1984 and 1990, he expanded the collection through regular acquisition committee meetings and gave the galleries a modern new look.

“Sihare’s expertise and exposure gave international fame to the National Museum,” recalled Sanjib Singh. “But after him, the museum was mostly in an apathetic state.”

Meanwhile, the crosscurrents of religion and politics had their own impact on the museum.

Religion in the galleries

On a Friday afternoon in September, the Buddha Relics Gallery seemed less like a museum hall and more like a shrine. Visitors sat cross-legged on the floor before a monk, palms pressed together in prayer. Some bowed low, others fixed their gaze on the relics in glass cases.

While museums in the West generally function independently of religion, in India that boundary has often been porous.

Back in 1973, when he was director of the National Gallery of Modern Art, Sihare had noted this in a New York Times interview.

“Religion has always dominated art here. A traditional Indian does not react esthetically and say, ‘That’s a lovely piece of sculpture.’ He says, instead, ‘That’s the God Shiva or Krishna.’”

Sihare’s words foreshadowed the fate of his final tenure at the National Museum in 1990. He was dismissed for serving alcohol to Western dignitaries on museum premises. Staff and politicians alike claimed it violated religious sentiments because the galleries displayed Hindu deities.

As cultural historian Jyotindra Jain has noted, the museum has for long “one of the fora” for the “politically inspired, resurgent reconstruction of the Hindu nationalist and ethical ideology.”

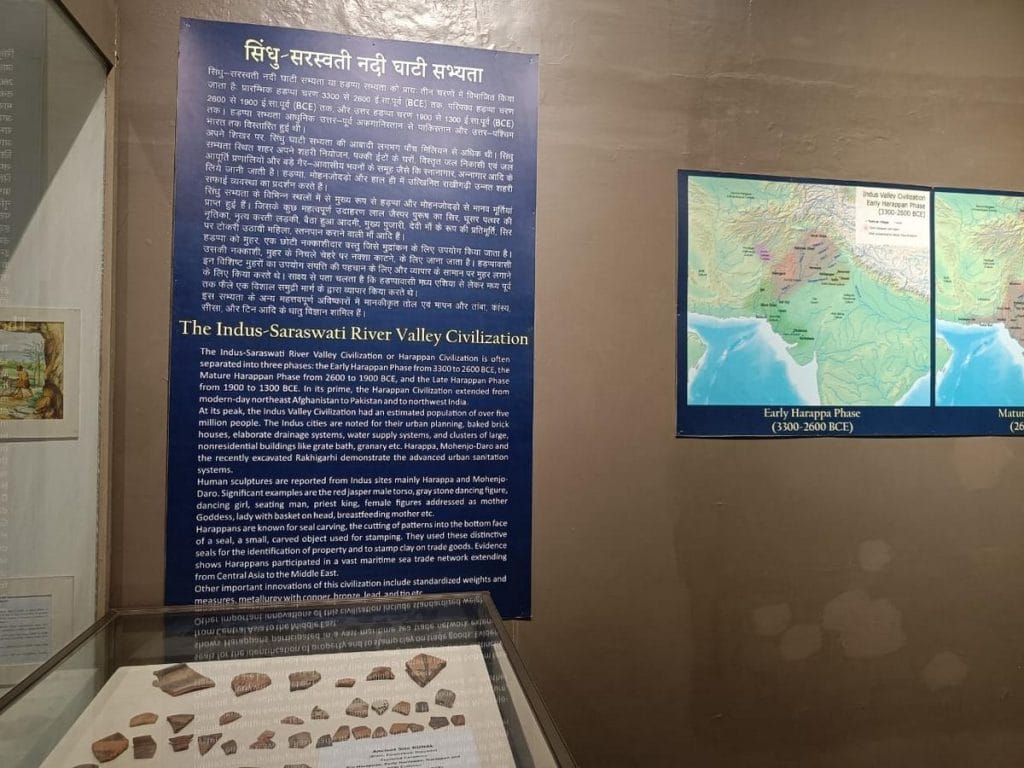

This became more pronounced in the early 2000s, when the Vajpayee government pushed to reimagine the Indus Valley Civilisation as the Sindhu-Saraswati Civilisation. In 2002, an expert panel headed by culture minister Jagmohan was set up to hunt for the ‘lost’ Saraswati. Captions in the Harappa Gallery were altered and banners of travelling exhibitions were changed overnight.

“Critics observed that the National Museum not only changed the nomenclature but also interpreted some artefacts in the gallery to establish that there was a Hindu theme in the beliefs and practices of the people of the Indus Valley civilization,” noted an article, ‘Musings on Museums’, in the Summer 2010 edition of the IIC Quarterly.

And in 2002, when the café began serving meat, right-wing groups burnt effigies of the director-general and demanded ritual purification of sacred objects in the museum.

Once the Congress came to power in 2004, the Saraswati hunt trickled to a halt until it was revived once again by the Modi government, with fresh digs launched to prove civilisational greatness.

Some text panels and charts in the National Museum captions in the Harappa Gallery now refer to the “Indus-Saraswati River Valley Civilization”.

And once again, food became the centre of a row. In 2020, the museum suddenly removed non-vegetarian food from the menu of a culinary event titled Historical Gastronomica: The Indus Dining Experience after two MPs complained. Archaeological evidence shows the Harappans had a robust appetite for pigs, cattle, and goats, but the revised menu replaced dishes like meat-fat soup and dried fish with khichri, khatti dal, and ragi laddoo.

Amid the uproar, then additional DG Subrata Nath admitted that certain unwritten museum traditions had to be followed.

“This museum has so many idols of gods and goddesses, and a relic of Lord Buddha. We have to consider these sensitivities here,” he said.

Now, the museum’s entire identity is due to be remade.

Also Read: Triveni Kala Sangam in Delhi is 75. Its family is building an archive

Reimagining history with Yuge Yugeen

At the International Museum Expo in 2023, PM Modi unveiled a walkthrough video of the Yuge Yugeen Bharat National Museum, billed as the world’s largest museum at 1.54 lakh square metres. Initially, the plan was to demolish the old National Museum, but government officials later said the proposal had been “put in abeyance” due to the challenges of storing the two lakh artefacts.

Meanwhile, India and France signed an MoU last year to develop Yuge Yugeen in the North and South Blocks of New Delhi through adaptive reuse.

“This project is aimed at showcasing India’s cultural heritage – a celebration of timeless and eternal India to explore our proud past, illuminate the present and imagine the bright future,” Union minister Gajendra Shekhawat said in Parliament this year.

The National Museum is languishing but not comatose. It needs someone like Jamvant to make Hanuman realise his powers

-Sanjib Singh, museologist

He added that unlike the old chronological format—Harappan to Gupta to medieval—the new museum will use concepts to narrate history. Vignettes rather than chapters, in essence.

“The new museum will show the history in a thematic manner such as the history of Indian crafts, the history of Indian architecture,” Shekhawat told ThePrint during the Gyan Bharatam Conference.

Sources in the culture ministry said Yuge Yugeen will cover 5,000 years of Indian civilisation, with artefacts such as Indus Valley terracotta hourglasses, Chola bronzes, and Gupta-era sculptures on display.

For some, the approach is a chance to light up the public imagination.

“The world changes and new situations demand new solutions,” said art historian and author Partha Mitter. “Yuge Yugeen Museum seems to be an ambitious project and is expected to contribute to Indian culture. The new museum will draw crowds to view Indian civilisation.”

However, the project has invited vociferous criticism as well. It is accused of prioritising glorification over history.

“It’s more about publicity and history deletion. History is not about glorification of the past, it’s about professional accounts,” said art historian Tapati Guha Thakurta.

With little known about the specifics of the new museum, many see political designs at play.

“No one knows how they are telling the story. It’s not about utility but about the immortality of a person. I objected from day one,” said Sircar.

In 2021, Kavita Singh also contended that the lack of transparency showed how little India’s current rulers cared about the museum’s public role.

Some long-time National Museum insiders, though, are more hopeful.

“The National Museum is languishing but not comatose,” said Sanjib Singh. “It needs someone like Jamvant to make Hanuman realise his powers.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)