New Delhi: Minutes before Indian astronaut Shubhanshu Shukla was set to lift off to space from Florida, the programmes team at Delhi’s Nehru Planetarium was frantically trying to connect the display screen in the sky theatre to the livestream of the launch. The schedule changes for the Axiom-4 launch left the planetarium staff in the lurch, having to arrange the screening at the last minute. But they were determined to continue the tradition.

“The last time an Indian had gone to space—Rakesh Sharma—we had screened his famous conversation with Indira Gandhi in this very planetarium,” said KS Balachandran, senior technician at the planetarium. “So obviously this time too we had to do the screening.”

However, unlike the previous screenings, such as Chandrayaan-III and Aditya-L1 in 2023, the Axiom launch one was quite muted. No banners and Indian flags, no full day of activities, just a quick announcement and a five-minute livestream before the pre-scheduled noon show. Once the core of Delhi’s science offerings, Nehru Planetarium today is a pale shadow of its grand, progressive past. Fewer and less varied shows, fewer astronomy research projects, and an almost dead amateur astronomers club indicate the dual crisis at the top—of imagination and of leadership. There hasn’t been a director since 2021.

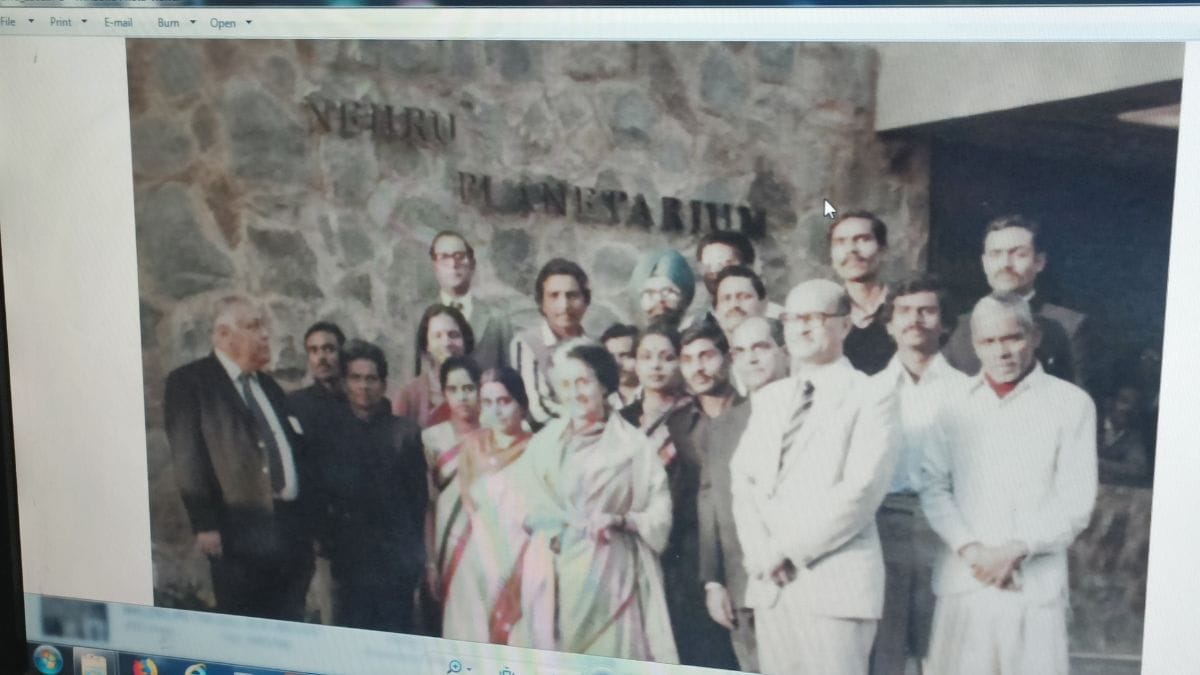

Inaugurated in 1984, the planetarium remains the only one in the capital, even as the city’s population has increased from around six million to 33 million in the same time. With two stellar past directors who hosted amateur astronomers’ clubs, telescope workshops, and field trips for Delhi schools, it boasts a rich history of fostering the city’s interest in the skies for the better part of four decades. It also created a group of astronomy enthusiasts in and around Delhi who link their origins to the planetarium. But after the last director, N Rathnasree, died in 2021 and no new director has been appointed since, the planetarium’s additional offerings have tapered off, and Delhi’s abode of stars is losing its shine.

“The reason Nehru Planetarium meant so much to all of us was because it was helmed by excellent directors who really wanted to propagate astronomy for the citizens,” said Ajay Talwar, vice president of the Amateur Astronomers Association Delhi (AAAD), which started in the planetarium in 1985.

Talwar was talking about astrophysicist Dr. Nirupama Raghavan, who was the director of the planetarium from 1985 to 1999, and Dr. N Rathnasree, who followed her from 1999 to 2021.

“You need someone special to build a community around it with offerings beyond the shows,” said AAAD member Sachin Bahmba.

The Nehru planetarium is by no means inactive; it still runs regular shows, school field trips, workshops and summer camps, and its science gallery is being renovated with interactive screens and virtual reality (VR) setups, set to open by August. But for its former patrons, the planetarium’s charm lay in the people who ran it, and that disappeared after 2021.

“A planetarium is essentially a show about stars and the sky – anyone can run it, but you need someone special to build a community around it with offerings beyond the shows,” said Sachin Bahmba, founder of Space group of companies, and a member of AAAD.

Astronomy pedagogy

“When Dr. Rathnasree was here, she would herself come up with new ideas, would invite colleagues, astronomers, physicists from across the world to give lectures and hold workshops,” said Prerna Chandra, programme director, Nehru Planetarium.

Prerna Chandra, the programme director at Nehru Planetarium, is always overbooked. She has to sometimes turn down requests from Delhi schools for private astronomy sessions, because the current two shows, monthly astronomy sessions and workshops, and lectures within the planetarium’s premises are more than enough for the staff to handle.

“The planetarium’s reputation for space outreach education in Delhi is unmatched. A field trip here is almost mandatory for every school student in the city,” said Chandra, sitting in her office inside the stone structure of the planetarium. “Students are our main audience, to whom our programmes are catered.”

The Nehru Planetarium is nestled inside the Teen Murti Bhawan in central Delhi, as a part of the Prime Ministers’ Museum and Library (PMML) compound. It has been an autonomous body under the Ministry of Culture since 2005.

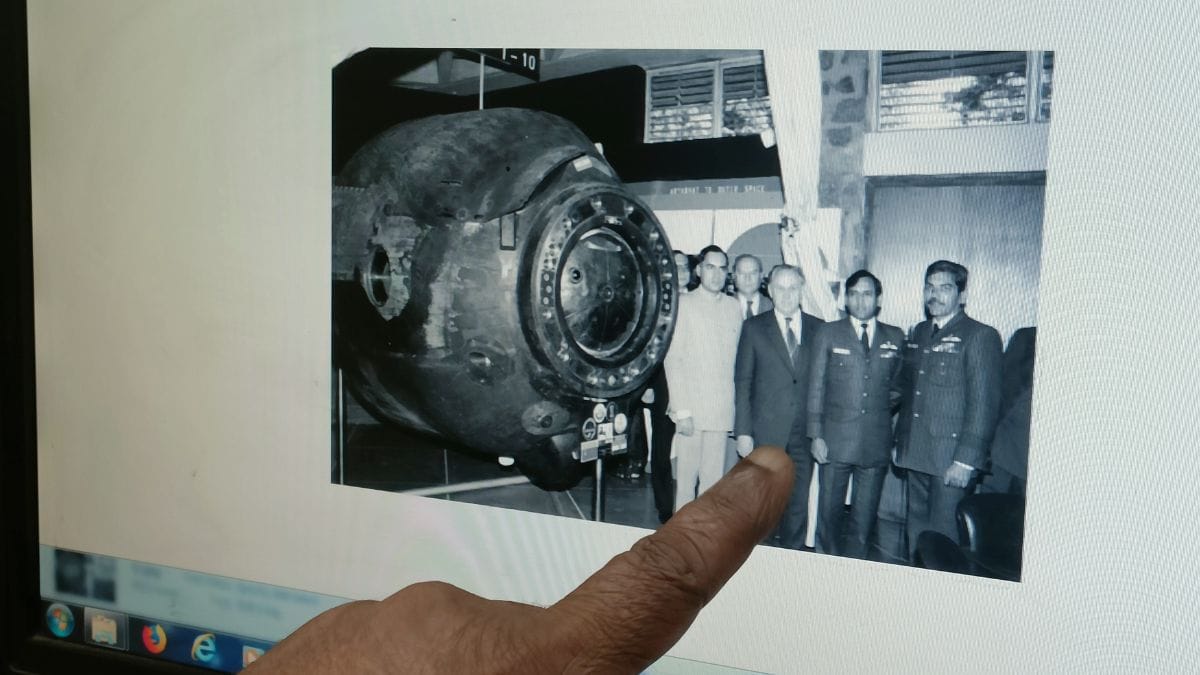

The planetarium is fitted with a sky theatre and a permanent gallery. The gallery exhibits some of the Planetarium’s most prized possessions – the original Soyuz T10 spacecraft that took Rakesh Sharma to space and was gifted by the USSR government to India, and the original spacesuit of Ravish Malhotra, who was the backup astronaut for Rakesh Sharma’s 1984 flight. Now, the gallery is being refurbished entirely with a total outlay of Rs 3 crore to fit it with interactive, touch-screen displays, activity corners for children, and VR sets.

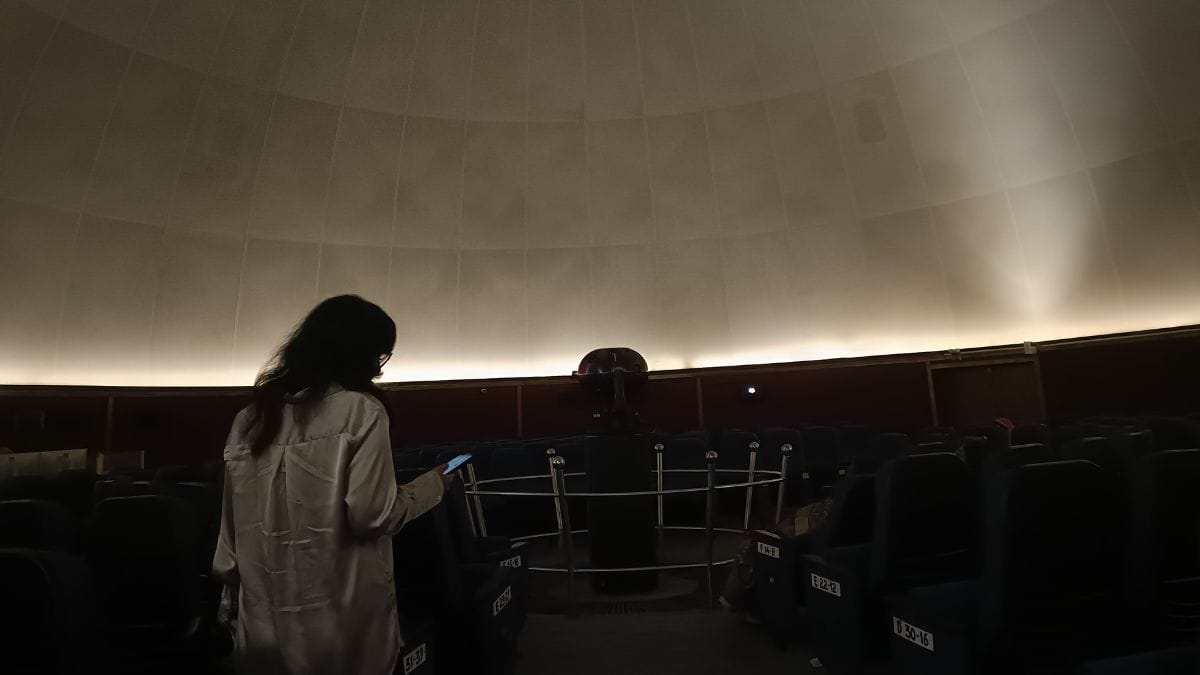

While the gallery has been under renovation since November 2024, the 250-seater dome-shaped sky theatre is the central attraction. That’s where the public shows are hosted. Since the all-new 3D system was installed in 2023, the theatre offers two shows—a 2D one called ‘Biography of the Universe’ and a 3D one called ‘Robot Explorer’. The tickets are priced at Rs 70 and Rs 100 respectively, with special discounts for school groups.

Keeping with the times, the planetarium has made its shows easy to book online on BookMyShow. It also has a Facebook page with some 5,000 followers where Chandra posts updates about shows, workshops, and summer camps.

However, the planetarium does not have an independent website, relying instead on a page on the PMML’s official website. This rudimentary page, too, is not updated with any information beyond show timings, with the ‘gallery’ and ‘student project’ pages remaining blank.

Right now, the planetarium also has no presence on Instagram or X, formerly Twitter. According to Chandra, though this has had no effect on the planetarium’s popularity.

“It is not just people from Delhi, but so many times I see people from Ambala, Bahadurgarh, Palwal, Jaipur also coming to visit the planetarium with their families,” said Chandra, who has been working there since 2019. “In summer, because most children have their vacations, we are quite full, and during school sessions, students visit from their schools.”

The average daily footfall is 2,000 people, according to the ticket managers. However, the official numbers vary from year to year. For example, in 2022-23, the planetarium only saw an annual footfall of 1.60 lakh because it was shut for three months due to renovations. In 2023-24, the number rose to 2.70 lakh, and in 2024-25, it was at 2.06 lakh people.

These are just the visitors for the shows, though. Almost since its inception, the Nehru Planetarium has had events beyond its regular shows. It hosts other public outreach programmes like night-sky observations, practical astronomy workshops for children, quizzes and lectures, as well as live screenings for events like Axiom-4 launch. Now, new private companies like Space India have emerged to provide some of these facilities for school children, but the planetarium continues to bear this mantle.

“In a way, it is good that there are new space companies now that offer space education to children in schools – the planetarium won’t be able to do everything after all,” said Chandra. “But none of them pose a competition to us because we still offer our programmes either free or for a nominal charge,” she added.

The initial idea of the Nehru Planetarium and its funding came from the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial Fund set up in 1964, in honour of India’s first Prime Minister. After 2005, the planetarium came under the administrative control of the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library (now PMML), which is managed and funded by the Union Ministry of Culture.

As seen in the public annual reports, the planetarium’s budget for maintenance and outreach programmes in the last five years has fluctuated quite a bit. While in 2019, 2020, and 2021 it was granted around Rs 2.5 crore yearly, in 2022-2023 the budget shot up to Rs 17 crore for the upgrade to a 3-D projection system, bought from the US-based Evans & Sutherland company.

But in 2023-2024, the budget slipped down to just Rs 54 lakh, while in 2024-25 it was Rs 80 lakh.

Also, within the main budget, it was the allocation for outreach programmes by the planetarium saw a dip after the renovation. Till 2022, it ranged between Rs 29-31 lakh, it went down to Rs 16 lakh in the year 2023-24, and then just Rs 11 lakh in 2024-25.

Under Dr Rathnasree in 2019, there were 14 different lectures and seminars, in addition to a two-month-long astronomy boot camp for college students, a Moon Carnival, and solar observation workshops held in 15 different cities. Given her own passion for these subjects, Dr. Rathnashree would helm many varied programmes not just in the planetarium but at Jantar Mantar too. In 2022-2023, the planetarium could only organise five lectures, a handful of workshops, and a few events to commemorate National Science Day and Space Week.

It was only after the pandemic and the renovations in 2023 that they found their footing again. In 2024, Chandra organised around 15 online and offline workshops and even managed to bring back the astronomy boot camp for college students. Eminent scientists such as Somak Raychaudhury and science communicators like Kshitij Pandey talked to students about black holes, neutrinos, and gravitational waves. This year, the focus is back on school children aged 8-15, whom the planetarium hosted for short weekend-long astronomy workshops in May and June.

“When Dr. Rathnasree was here, she would herself come up with new ideas, would invite colleagues, astronomers, physicists from across the world to give lectures and hold workshops,” said Chandra. “After her passing, the COVID pandemic brought some changes to programmes due to restrictions on public gatherings. But the quality of programmes and our offerings never wavered,” she added.

The height of the planetarium’s popularity though was under Dr. Rathnashree and Dr. Raghavan, according to Talwar. He recalled how in June 1997 when they were hosting a planetary observation night, 250 people turned up on Teen Murti Bhavan’s grounds for the event, and around 100 more people queued outside the gates to enter.

“Dr. Rathnashree finally went out the gates holding two telescopes, and made sure every person got a chance to see the sky,” said Talwar. “That dedication to the craft – it is unmatched.”

According to Chandra, the main function of the Nehru Planetarium, or any public planetarium, is to build an interest in space and conduct science outreach to the general public. For detailed studies in astronomy, there were other private companies in Delhi. But this wasn’t always the case.

Like Talwar, the erstwhile members of the Amateur Astronomers Association recounted how, under directors Raghavan and Rathnashree, the planetarium was the heart and soul of Delhi’s astronomy pedagogy.

History of the planetarium

It all began in 1985 when one day a large piece of glass broke inside the planetarium. OP Gupta, senior technician at the planetarium, recalled how, instead of throwing the pieces away, the director, Nirupama Raghavan, said they could use them to make a telescope.

“I don’t think many people who visit the planetarium would know how to make their own telescope – it is so easy, I think we should host a workshop,” Gupta recalled her saying.

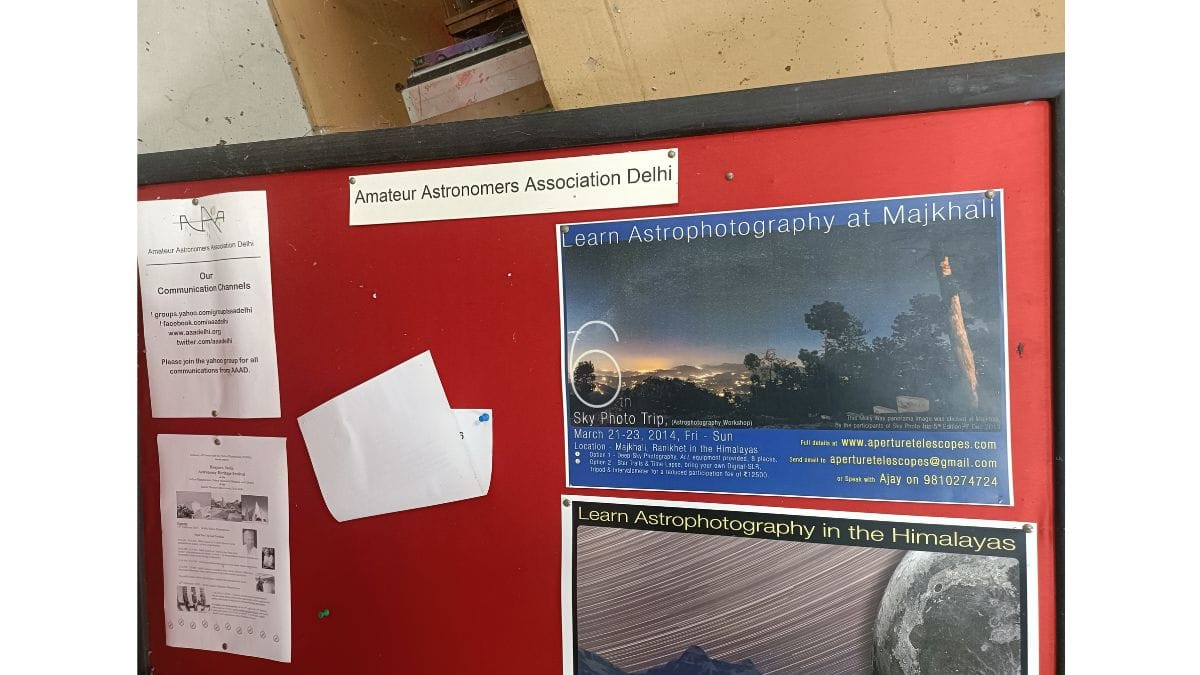

And so, a group of barely 40 people in a telescope-making workshop was the genesis of the AAAD. In its heyday, the AAAD had over 500 members who would gather for weekly meetings called ‘Sunday Noon at the Planetarium.’ From astrophotography to public stargazing sessions and calculating star occultations within PMML’s premises, the association’s various activities enhanced their interaction with the stars and the planetarium.

“Dr. Raghavan was the reason I got interested in astronomy in the first place,” said AAAD’s vice-president, Talwar. “The AAAD had a symbiotic relationship with the planetarium through her, since all our events were centred there.”

Virtually every astronomy enthusiast and astrophysicist from Delhi has a story that traces back to the Nehru Planetarium. Dr. Priyamvada Natarajan, a renowned astrophysicist at Yale University, said in a public interview that her journey in the field began when she was in school and Dr. Raghavan gave her an assignment to map Delhi’s skies.

Previous annual reports of PMML document how some PhD and Master’s students in astronomy also completed research projects in the planetarium. According to Chandra, though, since 2021, there haven’t been any research projects in the planetarium because there’s no scientist at the top to help mentor them.

The previous directors also took an avid interest in curating new, topical shows for the audiences with in-house production. Almost every year, recalled Gupta, there would be new shows on subjects like Mars, Supernovae and Pulsars, Venus Exploration created by the staff for limited displays in the sky theatre. From the optomechanical projectors in 1984, which needed to be hand-operated, to digital projectors in 2010, to now 3-D projectors, the technology of shows has changed with time.

Now, while there are no in-house shows made, the two ongoing planetarium shows are quite holistic in their content. ‘Biography of the Universe’ talks about the celestial world from the Big Bang to stars and planet formation. ‘Robot Explorer’ discusses important human strides in space exploration like the International Space Station, Voyager, and Mars Rovers, as well as ISRO’s missions. They are also rendered vividly with 8K resolution using an RGB laser projector, one of the only ones in the country.

“We also have a few other shows on Gaganyaan, Chandrayaan, asteroids other special topics but those are shows which are displayed on request by school groups,” said Chandra. “The general public may not always be interested in them.”

As for the topical events like Chandrayaan-III, they keep up with live screening events to generate a buzz and educate the public.

No more AAAD, but spirit lives on

“At the end of the day, we are still the Nehru Planetarium and our popularity is unmatched,” said Prerna Chandra

The COVID-19 pandemic, which was the reason for Dr. Rathnashree’s untimely death, was the last time the planetarium saw a full-time director. Now, Indranil Sanyal, who is an officer on special duty appointed to the PMML, is the director-in-charge of Nehru Planetarium, but the day-to-day is managed by Chandra and a 25-member staff.

The pandemic was also one of the last times the AAAD had their Sunday noon meetings, and over the last 5 years, the association has more or less faded into a WhatsApp group.

“We’re still interested in astronomy, but the connection with the planetarium has more or less disappeared,” said Talwar. “The reason for which we would congregate there—Dr. Raghavan and Dr. Rathnashree are no more.”

Its members still keep alive the passion for astronomy, through their own endeavours now. Ajay Talwar runs India’s own telescope manufacturing facility called Aperture Telescopes in Manesar. Sachin Bahmba, another member, founded the Space group of companies, to make space and astronomy education accessible to children.

In many ways though, the planetarium still claims its spot as the foremost institution for space education in the country’s capital and is actively striving to sustain it. In 2024, to celebrate Chandrayaan-III’s one-year anniversary, the planetarium hosted S Somanath, then Chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). This year, Chandra hopes to invite V Narayanan, the current head of ISRO.

“At the end of the day, we are still the Nehru Planetarium and our popularity is unmatched,” said Chandra. “To this day, I meet people at the planetarium who are learning about the night sky for the first time ever and are enthralled. Our main role is to serve the public’s scientific curiosity, and as long as we’re able to do that, I’ll consider our duty complete.”

As if right on cue, on a Wednesday afternoon, the sky theatre’s gates opened and a family of four walked out after their noon show of ‘The Robot Explorer.’ The two sons, aged 9 and 12, were chatting animatedly with their parents about what they saw inside.

“I can’t believe there is a space station up there where people live continuously – how cool to just float in space,” said the younger brother. “Do you think we can ever go there?”

“Arre haan didn’t you hear what the lady said inside?” chided the older brother. “Shubhanshu Shukla just went there!”

The article is part of a three-part series on state of planetariums in India. Read all articles here

(Edited by Ratan Priya)