New Delhi: Nearly 40 years ago, PK Nair bought his third-floor flat in DDA Yamuna Apartments, Alaknanda. Back then, climbing 48 steps was effortless for the young Army man. Today, at 84, those same stairs have become a battle, with every step slowed by weak bones, shortness of breath, and the absence of a lift he has been demanding since 2016.

“We are old now. If tomorrow one of us falls sick or worse, how will we go up and down? My wife can barely manage, and I find it very difficult too,” Nair said.

Delhi’s low-rise flats from the 1970s and 80s didn’t account for their inhabitants growing old. As residents age and become less mobile, lifts have become flashpoints for courtroom battles, neighbour disputes in RWA groups, and bureaucratic deadlock. Car parking was once the main conflict area. Now, the fight is over installing lifts. The DDA’s housing stock never anticipated today’s reality: a car in every home, ageing knees on every floor. Some buildings have basement parking, but only for scooters. And retrofitted lifts are a distant dream for most, even after policy finally made them possible.

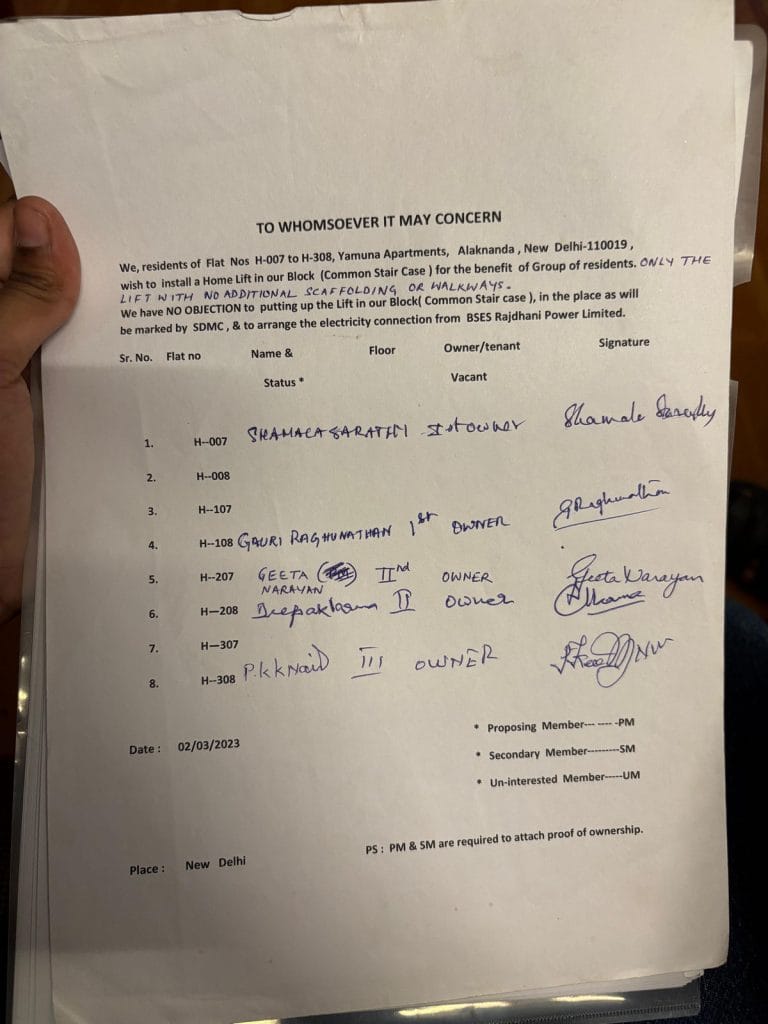

Ironically, the system had opened the door just as Nair knocked. In September 2015, the power to issue NOCs for lifts was shifted from the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) to local municipal bodies, with the South Corporation even launching a single-window system. Consent letters from just 50 per cent of residents using the common staircase were enough, officials said — the ground floor wasn’t counted. Detailed policy guidelines followed in February 2016.

Suppose somebody dies on an upper floor, how is the dead body to be brought down? Suppose somebody gets injured, somebody is pregnant, somebody is differently abled, how do those people come up and down? These are human rights issues

-Anil Dewan, retired dean (research), SPA

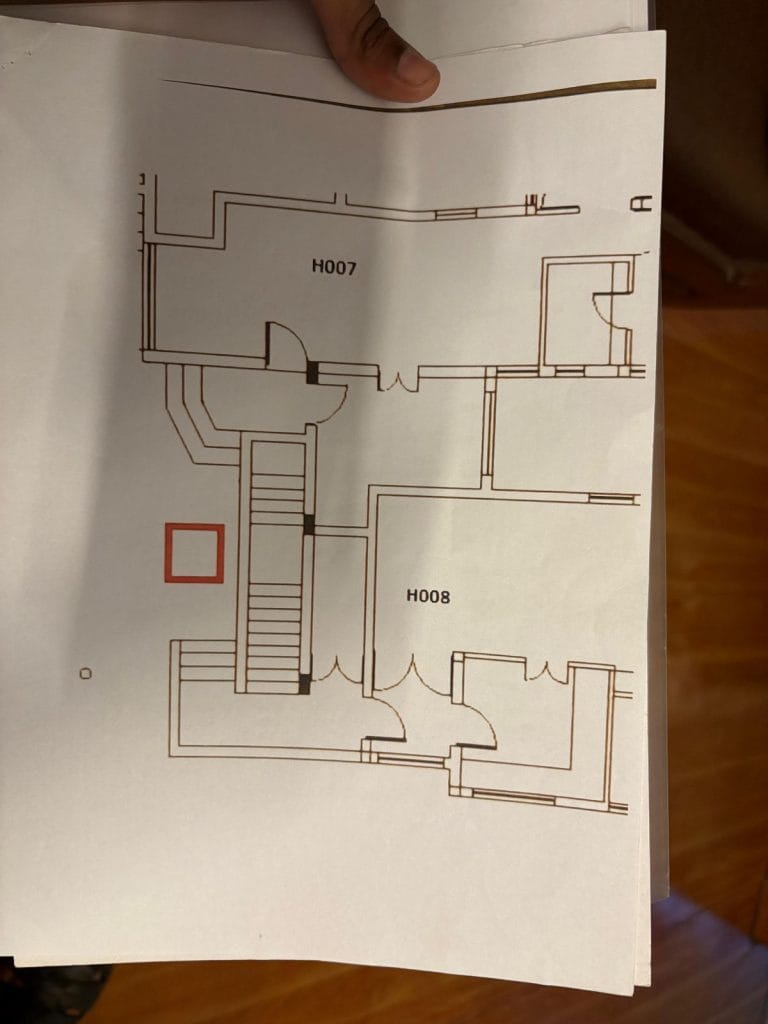

Nair wasted no time. Papers were filed, signatures collected, approvals secured. He got the NOC, and a pit was dug for construction. But then, residents on the ground floor objected. Work was abruptly halted and hasn’t moved since.

A similar battle is playing out across Delhi’s DDA and cooperative housing societies.

For many, the fight isn’t about luxury but survival: knees that buckle, breath that runs out halfway, and the indignity of waiting for reluctant neighbours to sign off. While some societies have managed to get lifts installed quickly, others have left their elderly and mobility-challenged residents stranded.

This, even though nearly a decade ago the MCD framed the ‘Detailed Policy for Installation of Lift and Connecting Bridge in Cooperative Group Housing Society (CGHS) Flats and DDA Built Flats (Low Rise Flats) in NCT of Delhi’ — approved by the Lieutenant Governor and based on the DDA’s earlier framework. It laid out procedures for permissions, NOCs, and structural safety, aiming to streamline what was already one of the capital’s most urgent housing challenges.

But executing the ‘lift policy’ has been far from simple. Ground-floor residents resist fiercely, citing fears of structural damage, loss of privacy, blocked sunlight and ventilation, and higher property values for flats above. Many disputes end up in court.

The Delhi High Court has repeatedly upheld the right to lifts, stressing that accessibility for the elderly and disabled outweighs objections over privacy or aesthetics. In multiple rulings, it has allowed installations that meet safety and statutory norms. But it hasn’t ended the uphill climb in many housing societies.

ThePrint contacted the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) for citywide data on how many residential societies, buildings, and DDA flats lack lifts, but the exact figures were unavailable. According to Mahendra Rustgi, a retired elevator executive who helped draft Delhi’s lift policy, there are roughly 500 Cooperative Group Housing Societies (CGHS) and about 45,000 DDA flats in the city. In 2018, only 8 of 75 group housing societies in East Delhi had reportedly secured lift approvals, while North Delhi had cleared just 10 of around 125.

Residents say the policy needs urgent reform, including stronger conflict-resolution mechanisms, firm timelines for objections, and better public awareness to reduce resistance. They also point to corruption and administrative gaps, alleging a nexus between MCD officials, architects, and lift operators who fast-track approvals for bribes.

Some even call it a human rights issue.

“Every policy must evolve continuously. Loopholes and obstacles should be identified and resolved. Residents on the ground or first floor should not have the power to block accessibility retrofits, because access to one’s home is a human right,” said Anil Dewan, retired dean (research) at the School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi. “Universal accessibility must be ensured for the elderly, pregnant, and differently-abled, no one can be denied entry to their own flat.”

Also Read: A DDA flat baithak brings intimacy back to Indian classical music. Beyond scale, spectacle

An apartment block divided

In Rohini’s Cosy Apartments, the lift meant to make life easier has ended up making it harder for Seema Garg and her 84-year-old mother, Santosh.

Seema’s out from 9 to 4, but with lift work ongoing, she’s constantly worried about her mother being home alone. Despite her clear objection, the lift was installed in the block. Her second-floor balcony now opens directly beside the shaft.

“First of all, there is no light. It’s dark. If someone comes, I can’t see if anyone is standing or not. The lift shaft has swallowed the open balcony and anyone can see into our house from the opening of the lift door — everything is visible,” she said, uneasy with the sudden loss of privacy.

To preserve some privacy, builders fixed a flimsy green fibre sheet, which later collapsed, damaging her tulsi and flower plants.

“Since that day, my mother’s medicines have increased. I am showing her to a psychiatrist. She is old, and this insecurity causes so much mental torture,” Seema said, looking at her mother who struggles with hearing.

The previous RWA had opposed installing lifts inside stairwells, according to Raman Tuli, the apartment’s former secretary.

“Lifts cannot be installed in the stairs at all. We proposed shared lifts in common areas with proper passages, but the new committee ignored this and began unauthorised installations,” he said.

For 40 years, we lived in harmony. Now, we are becoming enemies. Love and affection have been left in the middle of this fight

-Raman Tuli, resident of Cosy Apartments

Tuli added that people had built these homes with years of savings. Some paid a premium or took loans for ground-floor flats because they were more accessible for the elderly.

“Sunlight, ventilation, space—everything is being destroyed because of poor planning,” he complained. “If lifts are for senior citizens, why are they blocking the air and light of elders living on the ground floor?”

Others, however, wholeheartedly disagree with this view.

Ranjan Bargotra, a member of the managing committee of Cosy Apartments, began advocating for lift access in 2020 after his elderly mother became unable to climb the stairs. She died the following year.

“We were on the third floor. There was a time when we used to take four people to put her on a chair and take her to the third floor. It was quite an effort,” said Bargotra.

He added that his plea for lift installation was met with silence and resistance from the previous committee.

“I wrote the first letter in 2020. I had written at least a dozen letters. No response. So much so that some twenty to thirty residents waited outside the managing committee’s office to talk. We were not allowed to get in,” he said.

We’ve kept the message [about installing lifts] positive, focused on inclusivity—not confrontation—while strictly adhering to the law and due process

-Ranjan Bargotra, managing committee member of Cosy Apartments

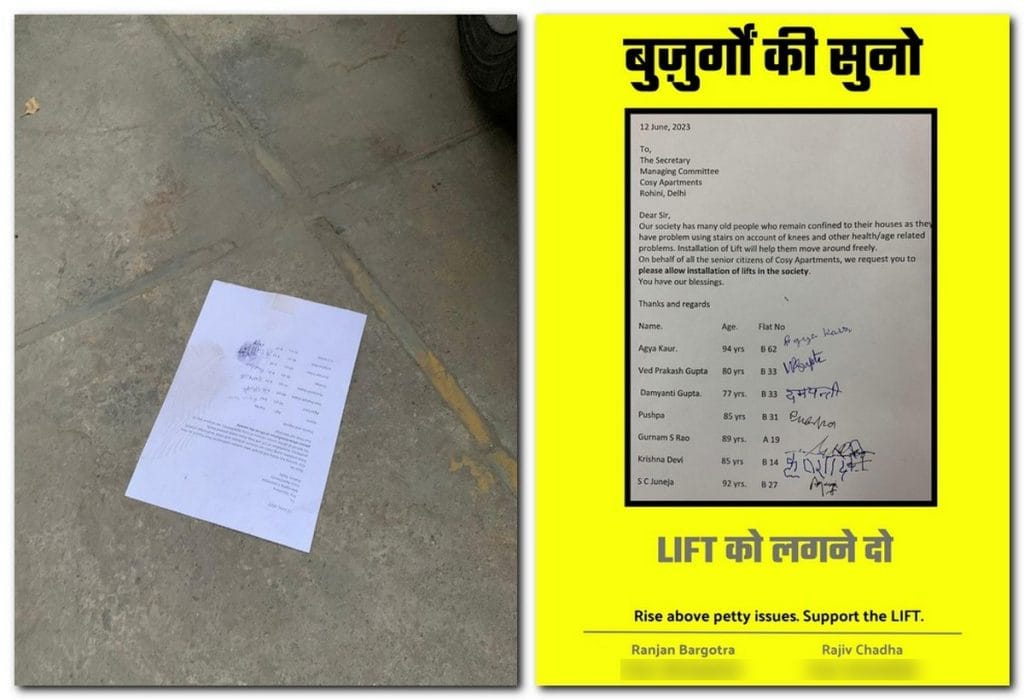

Bargotra claimed that appeals signed by elderly residents—including a 92-year-old woman—were torn and discarded next to his car. Posters he put up, with messages such as “Buzurgo ki Suno” (Listen to the elders), were torn down.

As a response, he mobilised fellow residents who were also struggling, contested the society elections, and formed a new committee, elected unopposed.

As part of the new managing committee, his top agenda has been to install lifts. “We’ve kept the message positive, focused on inclusivity—not confrontation—while strictly adhering to the law and due process,” he said.

But the community divisions are simmering unabated. “For 40 years, we lived in harmony. Now, we are becoming enemies. Love and affection have been left in the middle of this fight,” Tuli said.

In two neighbouring societies, lifts are already up. Saathi Apartments runs on a single lift serving all floors, while Bhagirath has block-wise lifts. Most are smaller than policy norms, barely spacious enough for three people to squeeze in. Yet residents there seem content. The lifts, they say, don’t intrude on open space or compromise privacy and ventilation — a trade-off they’re more than willing to accept.

The anti-lift lobby

Delhi has thousands of residential societies built in an era when lifts weren’t mandatory for low-rise buildings like four-storey (G+3) DDA flats and builder floors. A section of residents argue it should stay that way.

The process to get a lift is mired in paperwork, but the policy’s site inspection provisions are far less rigorous.

Under the policy, applicants must submit certified drawings, detailed plans, and engineering certificates to the MCD, which “shall scrutinise” them. However, the MCD “reserves the right” to conduct physical inspections. This means inspections are not mandatory but discretionary. This creates a loophole where approvals are often granted based on submitted documents alone, without thorough on-site checks.

[MCD officials] tell you to apply for lifts, give you operator contacts, and they handle the rest. They demand up to Rs 2.5 lakh to get permissions without inspections

-Resident of Cosy Apartments

Many residents argue that installing lifts retroactively in narrow stairwells not designed for them puts health, safety, and privacy at risk.

When Cosy Apartments resident Sumit Pant requested a site inspection from the Fire Department, officials agreed the proposed lift location was unviable. But because the building was under 15 metres, they said it fell outside their jurisdiction, leaving residents once again without recourse.

“The proposed lifts violate the Unified Building Bye Laws for Delhi 2016, and the minimum widths for stairways and emergency passages are being ignored. Safety concerns are paramount,” Pant said.

The lack of a democratic process to decide on lift installation adds to friction, according to him.

“Only three out of eight flats consented to the lifts — 37.5 per cent. Is it right to ignore the dissent of more than 60 per cent? How can fire safety, ventilation, and lighting concerns be dismissed so easily? If ease of access to residents of higher floors is so important, why not make lifts mandatory in the plans for new buildings of Ground Plus 3 floors. Why force lifts on old buildings now?” he said.

ThePrint tried to speak to Cosy Apartments residents who were in favour of the lift but they refused to discuss the matter.

Many are disgruntled with what they call the policy’s one-size-fits-all approach, which ignores differences in layout, space, sunlight, and ventilation.

The MCD has thousands of registered architects, and one is randomly assigned by the concerned officer. There’s no scope for any collusion or nexus in the process. Wherever an inspection is necessary, the MCD does carry it out and if that’s not happening, then it absolutely should

-Manoj Kumar, assistant engineer in the MCD’s Building Department

Tuli and other residents have repeatedly written to the Deputy Commissioner of MCD’s Rohini Zone, warning that passageways will be narrowed to barely 3.5 feet, jeopardising emergency access and firefighting efforts. They also flagged the proximity of the lift shaft to electricity lines as a hazard, but to little avail.

Attempts to arrive at a compromise also went nowhere.

Resident Yogesh Seth personally hired an architect for Rs 20,000 to draw up alternative lift plans, including three viable options along the blind wall, and on the backside of the building. The managing committee ignored them due to higher installation costs.

“We’re not against lift installation, but it should happen with mutual consent. The MCD isn’t overseeing anything. People are doing whatever they want. In some societies, parallel committees are forming to oppose managing committees, and it’s creating deep divisions. I fear the same will happen in ours,” said Rajesh Seth, a resident on the ground floor.

Lift proponent Bargotra, however, alleged that the alternative lift plans that Yogesh Seth gave were not practical and couldn’t be implemented due to structural concerns.

“Sure, the passage gets narrower,” he said. “But it’s still wide enough for a person, even a wheelchair, to pass through. I told the residents that I understand it may cause some inconvenience, but for the greater good, for those suffering upstairs, please allow it.”

Meanwhile, several residents alleged collusion among property brokers, managing committees, MCD officials, and lift contractors. Upper-floor residents are allegedly urged to apply for lifts and promised higher resale values once installed, with quick approvals available for a price.

“They tell you to apply for lifts, give you operator contacts, and they handle the rest. They (MCD officials) demand up to Rs 2.5 lakh to get permissions without inspections,” claimed a resident, asking not to be named.

Manoj Kumar, assistant engineer in the MCD’s Building Department, dismissed the allegations outright.

“These claims are completely unfounded,” he said. “The MCD has thousands of registered architects, and one is randomly assigned by the concerned officer. There’s no scope for any collusion or nexus in the process. Wherever an inspection is necessary, the MCD does carry it out and if that’s not happening, then it absolutely should.”

Stalled by ‘spite’?

PK Nair leads an active life — building a cabinet here, fixing a door there, always tinkering with something. An Army cap in place, he drives a WagonR and hums old Hindi tunes, quick to flash a warm smile. But when it comes to climbing up to his third-floor Alaknanda apartment, which he shares with his wife and son, it’s been a struggle that’s both physical and emotional.

With a weary sigh, he rose from his chair and pulled out a thick folder he’s been building since 2016 — lift policy documents, court judgments, committee minutes, and NOC proposals, all neatly filed.

“Six out of eight owners signed in favour of the lift, but the managing committee still refused. The ground-floor residents opposed it, worried the value of upper floors would rise if the lift got installed,” he said. “I’m 84 now, it’s exhausting to climb the stairs. I just want to live the rest of my life in peace.”

Rustgi agrees that the Delhi lift policy, which he helped draft, has yet to take off. After two decades at Otis Elevators, he now runs his own company installing lifts, mostly for elderly clients.

“Most of the SFS flats in Delhi were handed over between 1982 and 1990. These buildings were constructed as ground plus three floors, and at the time, there was neither a lift nor any provision—or even space—for lifts,” he said.

As residents began to age, several RWAs petitioned the Lieutenant Governor and the DDA for a policy allowing lift installations. The proposal envisioned separate shafts connected to the existing floors via short corridors.

That policy eventually took shape. And Rustgi was there when it did.

[Ground floor residents] have no real stake in the installation of lifts. Their opposition often stemmed from sheer spite, not reason

-Mahendra Rustgi, retired elevator executive who helped draft Delhi’s lift policy

“We formed a committee, and held multiple meetings with the then Lieutenant Governor and DDA officials. Eventually, we succeeded in persuading them to remove the requirement for ground floor residents’ consent — because they have no real stake in the installation of lifts. Their opposition often stemmed from sheer spite, not reason,” he said.

Cooperative housing societies have subsequently taken advantage of the process to stall projects, according to him.

The policy requires a managing committee’s approval if common services like water, sewer, or electricity lines need relocation. When that approval is not given—as is often the case—applications to the MCD are left pending.

This has created a deadlock where managing committees, particularly those invested in ground floors, can hold entire buildings hostage.

“It’s essential that the policy be revised to correct this anomaly,” Rustgi said. He noted that most cooperative society flats have been converted to freehold under the Apartment Ownership Act, giving residents proportional ownership of common areas.

“As a result, consent from managing committees should no longer be a major hurdle. Similar to DDA flats, the responsibility should lie with applicants to manage the relocation of civil utilities in coordination with the RWA or managing committee.”

He added that once this is clarified, the policy would finally work.

But the MCD’s Manoj Kumar argued those checks exist for good reason.

“If someone has genuine concerns about ventilation or sunlight being blocked, the policy clearly states that a lift cannot be installed in such cases,” Kumar said. “It’s always preferable to install lifts on blind walls, and that’s explicitly mentioned in the guidelines as well.”

The Alaknanda case is currently pending before the Delhi High Court. The proceedings have been stalled for nearly two years. Hearings typically begin with a brief representation before being repeatedly postponed. Frequently, on scheduled dates, neither judge nor lawyer is present, leading to further delays. The next hearing is now scheduled for later this month.

Desperate for resolution, Nair has tried everything within reach, including turning to elected representatives.

Earlier this year, he met BJP MP Bansuri Swaraj, who was born in the Alaknanda area, and explained his situation. He asked her to submit a representation to the DDA vice chairman and Lieutenant Governor, citing the Apartment Act that converted flats to freehold.

“Although she claimed to have sent a letter, she couldn’t produce a copy even after six months. Despite repeated promises, she hasn’t taken any action,” said Nair.

Now he’s pinning his hopes on more ageing residents becoming aware of the issue and raising their voices.

Also Read: Indian cities are a mess of overhead wires. Delhi will pay Rs 8 cr to clear just 5 km

Unsafe by design

At Gharonda Apartments in Shreshtha Vihar, a lift that was approved in 2022 is now in limbo after a single objection.

Everything seemed to be going smoothly when resident SS Chouhan, then 75, and other elderly neighbours set about getting a lift installed under the Delhi policy. They agreed on a site, filed the paperwork, and got their NOC. Then a ground-floor neighbour filed an objection about light, access, and ventilation—and the work was frozen. A revised NOC followed in August 2022 for a location the initial petitioners found unacceptable.

Advocate Gaurav Bhardwaj, representing Chouhan, took the matter to the Delhi High Court. He argued that the policy says ground-floor consent is “advisable” but not mandatory, and that the revised location undermined the original lawful permission. Last December, the court said that the rights affected— light, air, and access—were valid concerns under the policy but passed the case to the Appellate Tribunal for the MCD, where it is still pending.

With modern times, the policy should come where these apartments are completely demolished, within a defined time frame, and reconstructed as high-rises. That way, we create more space and better accessibility for everyone

-Prof Anil Dewan

Amid these debates about whether or not to install a lift is another question—what kind of lift?

Architect Anil Dewan said most retrofitted lifts suffer from “poor levelling, unsafe standards, and low-quality installations”, with local manufacturers ignoring safety protocols.

He advocates stricter rules for certified lift manufacturers, long-term warranties, and five-year maintenance contracts.

“There are hydraulic lifts now… very good new technology. Some don’t even make noise. Some can generate electricity while coming down,” he said. “Suppose somebody dies on an upper floor, how is the dead body to be brought down? Suppose somebody gets injured, somebody is pregnant, somebody is differently abled, how do those people come up and down? These are human rights issues.”

Bhardwaj added that for the elderly, the absence of reliable lift access isn’t just inconvenient, it isolates them physically and socially.

“They should have the accessibility to go to the park, go to the market, have the freedom to go out without any strain or thought process,” he said.

While retrofitting may offer short-term relief, Bhardwaj contended that the real answer lies in rebuilding.

“With modern times, the policy should come where these apartments are completely demolished, within a defined time frame, and reconstructed as high-rises. Instead of two buildings with four floors each, we should have one tower of eight. That way, we create more space and better accessibility for everyone.”

Still, he acknowledged the complex political and economic realities of such an ambitious transformation—and the quagmire of consensus it would entail.

A lift that never came

Renu Tomar wanted a lift for her 76-year-old mother-in-law, who was struggling to climb the stairs of their DDA apartment in Vasant Kunj. Tomar hoped a shared lift would make the final years of her life a little easier. But what followed was a five-year legal battle that outlived the woman it was meant to help.

“She never got to use the lift,” Tomar said. “She passed away last year, waiting.”

The lift was built, but not by consensus. Tomar’s neighbour, Vikram Singh, installed it unilaterally in what she alleges was a shared common area meant to serve multiple flats.

“There was an understanding that the lift would be for everyone, and costs would be discussed,” said Tomar. “But he never consulted us, never shared any details. He just built it for himself, extending it illegally up to the fourth floor.”

According to policy, lifts in DDA flats can only go up to the third floor. In this case, the lift stopped at both the third and fourth floors, but Tomar was denied access — the doors opened only on her neighbour’s side. Though their flats are in the same block, they’re reached by different staircases.

The MCD backed her claim. After investigating, it revoked Singh’s permission, declared the structure unauthorised, and issued demolition and sealing orders under the DMC Act. Tomar, who had first filed a civil suit, later withdrew it and approached the Delhi High Court to ensure the MCD’s orders were enforced.

The court ruled in her favour. The MCD scheduled demolition for 25 November 2024, pending police assistance and lifting of restrictions under GRAP. Singh, however, has challenged the ruling in the Supreme Court, maintaining was never served the demolition order and that “nothing about the lift is illegal”. The lift’s still there, albeit unused.

For Tomar’s family — who’ve lived in Vasant Kunj since 2006 and run a water treatment plant — the case is about respect, fairness, and access.

“It’s been five years since that lift was installed,” she said. “It’s been sealed for three. We’re still fighting.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

A balanced piece. The point is lift should be built in blind sight and as far as accommodate those who live on ground floor. Light and ventilation is a real issue and not a flimsy one.

It should not be that might is right. The policy itself is flawed. The ground floor owner paid extra money for the apartment and why should he suffer.

I cannot believe a news site has done this… A media company is supposed to be unbiased but showing such a one sided story does not seem very unbiased media like. Where are the interviews from anyone suffering and in actual need of access. Where are the interviews from people on the third floor ..?