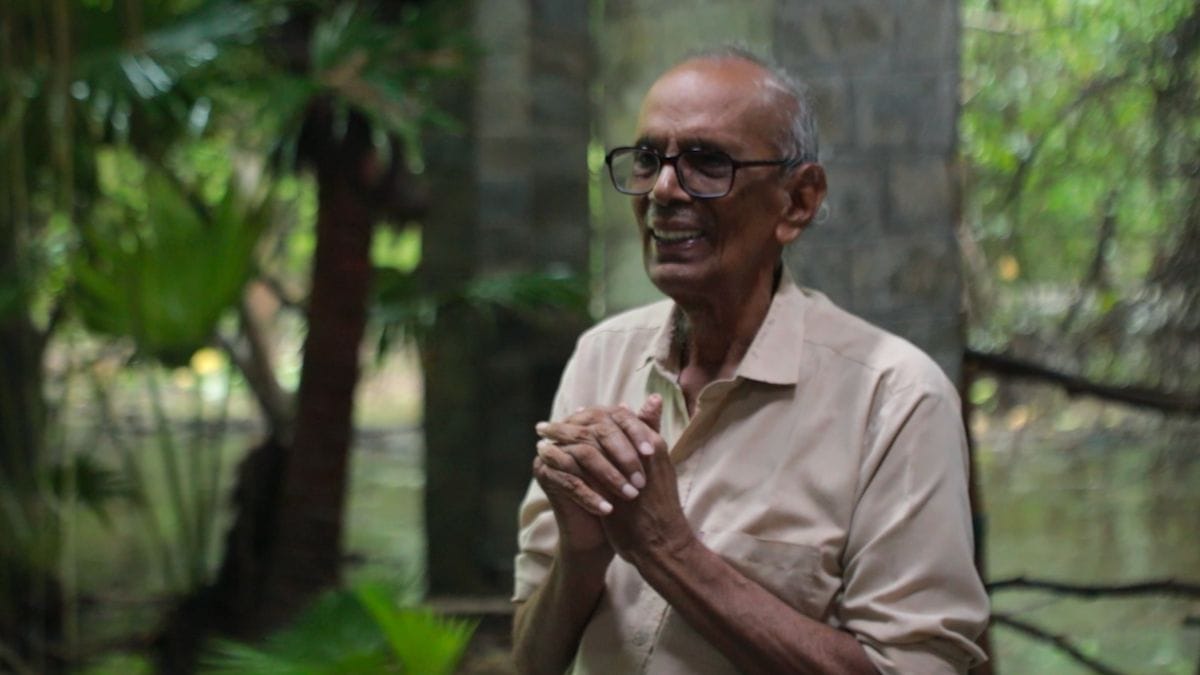

New Delhi: Eighty-five-year-old CR Babu knows exactly where each tree in the 457-acre Yamuna Biodiversity Park is planted. After all, he is the tree man of Delhi’s enviable green cover. His intimate knowledge of trees and passion are the fuel that drove Delhi’s successful biodiversity park revolution.

Nearly 25 years ago, this once-degraded piece of land on the banks of the River Yamuna was overgrown with weeds, dried bushes, and packs of dogs feasting on waste strewn by nearby villagers. Today, the park is teeming with over 900 varieties of trees, a growing wildlife population, a one-of-a-kind butterfly park and an herbal garden.

Delhi’s seven biodiversity parks—Aravalli, Neela Hauz, Northern Ridge, Tilpath Valley, Tughlakabad, and Kalindi—have become an unprecedented template for successful urban forestry projects in India. It has provided the much-needed lungs to a city otherwise infamous for toxic air pollution, garbage mountains and clogged roads. And it is an unlikely combo of DDA and Delhi University that has pulled this off.

“When I got this project, this piece of land was barren. The underground water was so saline that for nearly a year, every seed that we planted here died,” said Babu.

But Babu, a former Delhi University pro-vice chancellor and the head of the Centre for Environment Management of Degraded Ecosystems (CMEDE), and his team did not give up. They have turned this barren land into a lush urban forest—a “fully-functional ecosystem”, as he calls it.

The city’s first biodiversity park in Wazirabad is now the only thriving section of the otherwise dead Yamuna River in Delhi. It is home to a range of wildlife, including the civet cats, wild boars, various types of snakes, birds, and even a family of leopards.

Following its success, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA)—the land-owning agency in charge of the upkeep and maintenance of these parks—initiated the process of developing six additional parks.

Not just in Delhi, these parks were also replicated in Noida and Gurugram. And these urban forests have become a vibrant space for communities of walkers, joggers and cyclists and have stood as bulwarks against concretisation and sprawl.

An official at Gurugram’s Aravalli biodiversity park, which was leased out to Hero Motocorp by the municipality in 2020 to improve its upkeep, said that this man-made forest right at the heart of the city has not only managed to keep the pollution levels in the area under control, but has also revived soil health and improved groundwater levels.

“There are two AQI (air quality index) monitors in this area. On peak pollution days, when the monitor outside maxes out, the levels inside the park gates remain in the 100-150 range,” the official. “These are the only surviving green lungs of Delhi-NCR.”

When I got this project, this piece of land was barren. The underground water was so saline that for nearly a year, every seed that we planted here died

– CR Babu, the man behind Delhi’s biodiversity park project

Barren lands turned to forests

Standing on the viewing deck of Gurugram’s Aravalli Biodiversity Park, Prabhat Singh Yadav, one of the park’s caretakers since its inception in 2012, looks down at the greenery from one of the viewing decks.

It looks like a carpet, encompassing all shades of green.

But till less than a decade ago, this 400-acre piece of land was a haven for illegal stone mining.

“The entire park used to look like a beaten shade of brown. The illegal miners had dug up the entire place,” Yadav said.

Today, the park is a major attraction among families, school students and couples who want to spend time away from the crowds and chaos of the city. Even on days when the ‘Millennium City’ was inundated, visitors were lining up in the park to enjoy the rain amid nature.

Durgesh Singh, a 22-year-old student, visited the park with his friends in the first week of September when torrential rains hit Delhi-NCR.

The trio rode their motorcycles and spent nearly an hour clicking pictures and teasing each other, all while getting drenched in the rain.

Outside the park gates, the roads are knee-deep in water. But inside, the greens are happily gulping down the silver raindrops. The soil is moist, with a faint petrichor, and tiny streams in the forest are slowly guiding the water deeper. All like a well-oiled machine.

There was a time when the underground water level of the park was over 90 metres. Today, it is at just 34 metres, proving its groundwater recharge abilities.

Its counterparts in NCR have also been resurrected from the dead.

Delhi’s Yamuna Biodiversity Park was once a barren wasteland on the banks of the thinly flowing Yamuna. The saline levels of the soil were so high that it killed anything that tried to lay roots. The Aravalli Biodiversity Park in south Delhi—the other side of the Aravalli belt—was also an abandoned stone mine where illegal operations ran for decades, and the Neela Hauz biodiversity park was a drain.

A senior official from the DDA said that till the 1990s, illegal mining was rampant in Delhi-NCR. Large swaths of government land along the Aravallis used to be exploited by the mafia. These government lands were reclaimed after multiple court orders directed agencies to crack down on mining in the capital. By the early 2000s, when they were reclaimed, they were as good as dead.

“How do you think all these posh colonies of Gurugram were built? The original terrain of that part is rocky. The stones, mostly illegally mined from the Aravallis, were used by builders to resurface the land, over which these posh localities now stand,” the official said.

On peak pollution days, when the monitor outside maxes out, the levels inside the park gates remain in the 100-150 range

– An official at Gurugram’s Aravalli biodiversity park

A collaborative effort

In Delhi, the biodiversity parks project was initiated by then-Lieutenant Governor Vijai Kapoor. He envisioned that such spaces would be crucial to fighting the growing air pollution in the city.

He brought Delhi University’s CMEDE on board. DDA would provide the land and the resources to revive these lands, and the scientists from CMEDE would bring their expertise.

The project started with the Yamuna Biodiversity Park, which was opened in 2004, soon followed by Delhi’s Aravalli Biodiversity Park in 2005.

According to the DDA website, the goal of the parks was “conservation and preservation of ecosystems of the two major landforms of Delhi, the river Yamuna and the Aravalli hills.”

Babu, who was already a pioneer in reviving degraded ecosystems in the Himalayas, became the obvious choice to head the project. He said that the biodiversity project has always had the support of every L-G since Kapoor, irrespective of their political leanings.

“Initially, we got about 156 acres of land for this park (Yamuna Biodiversity Park). Now it is about 457 acres. The beauty of these parks lies in the fact that each one employs a different restoration technique. That is primarily because each park has a completely different terrain, ecology,” Babu said.

Babu’s team of nearly 20 scientists from the Delhi University are currently leading the charge. This involves tasks such as plantation, data logging, and setting up new ecosystems in these parks.

While Babu, despite his age, remains very much involved in the day-to-day operations of the parks, he has chosen a worthy second-in-command.

Faiyaz Khudsar, a renowned conservation biologist and senior scientist from Delhi University, is actively taking care of the project.

Since the project began, the understanding was that DDA would provide the land, be responsible for the parks’ maintenance, and provide all the financial backing for its upkeep. Delhi University would bring in its scientific expertise for the development of the parks.

All seven parks today collectively have over 150 employees—educators, gardeners, security guards—taking care of it.

Encroachments and legal battles

These parks are Delhi’s success story, even after over two decades, but authorities are fighting to maintain them. Some, against encroachments, others against legal disputes and visitors without civic sense.

Nearly all of these parks are located around densely populated human settlements. This means that the boundary walls of the parks are also often broken down by vandals, and the dense forests are used by criminals to carry out illegal activities.

“When the boundary of the park was marked, some villages around it claimed ownership and moved the court. Every now and then, they break down the walls. Many of these villagers also continue to use the parks to graze their cattle. All of it is illegal, but how much can we control it?” Yadav said.

These parks are also paying the price of popularity. As more visitors come in, they also bring plastic wrappers, bottles, and other trash that are often carelessly strewn around in the forests.

A security guard at the Delhi Aravalli Biodiversity Park, who did not wish to reveal his identity, said that plastic bottles and packets of chips and snacks are not allowed in the park, but it is difficult to scan every visitor.

Since the entry to these parks is free to the public, with limited manpower, it becomes all the more difficult. Hooligans misbehaving and roughing up the security staff, refusing to leave the park during closing hours or insisting on damaging trees and other property have become part of their routine. CCTV cameras are present only at entrances and viewing points, not deep in the parks.

“There are only two guards in the main entrances. How many people will we check?” he said.

But the biggest challenge facing all these parks is encroachment. From religious structures to unauthorised shops and slum clusters— it’s all eating up the designated parklands.

“DDA conducts anti-encroachment drives, but some of the cases have reached the court, and till the matter remains sub-judice, we cannot do anything to remove them,” the DDA official said.

A part of the community

It is 7 pm on a Wednesday, and Babu is at his office in the Yamuna Biodiversity Park, preparing his presentation for a group of students who are due to visit the park. He has spent the last week sending newspaper clips and archival photos to his team to include in their nature walks.

His nature walks never follow a routine. It is always different, specially prepared keeping in mind the backgrounds and ages of people attending it.

“He (Babu) is very particular. If we have a group of college students from an arts college, we will have our talks in a way that they can understand and connect it to their experiences,” an educator at the park said.

The aim is to get the people of Delhi, especially the younger generations, excited about nature. And to achieve that, the park has experimented with a host of interactive activities such as quizzes, photography sessions and games.

One attraction is its butterfly park, where the team hosts observation and photography sessions for students to track the developmental cycle of butterflies. They also have an indoor museum detailing a list of flora, Ailanthus, Butea and Bauhinia, etc, fauna, leopard, nilgai, civet cats, and wetlands that are part of the park now.

With these thriving parks in the heart of the most polluted capital city in the world, nature has proved that it has the power to heal itself—if humans give it a chance, say experts.

“Reviving degraded ecosystems has never been about just planting trees. It is much more than that. It happens when every part of the ecosystem—plants, animals, soil and even insects—comes together. And we have managed to build that ecosystem here in Delhi,” Babu said.

And right at that moment, a family of wild boar—who had disappeared from Delhi’s landscape till a decade ago—peeps into his office, proving his success.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)