Bengaluru: Midway through a coconut-harvesting project in 2011, Gokul NA, then an engineering student, understood one thing about robots — “they are dumb.” His BTech project was to design a machine that could select and pluck coconuts but it fumbled blindly. He had failed at building a “smart” autonomous robot.

Nearly 15 years later, the Bengaluru-based engineer-turned-entrepreneur has made it his business to solve this missing piece in automation. His start-up CynLr (short for Cybernetics Laboratory), co-founded by Nikhil Ramaswamy in 2019, is creating vision systems for robots to recognise and handle even unfamiliar objects. Not through programming but an ability to learn on the fly. To create these intuitive systems, the company has teamed up with neuroscientist SP Arun at the Centre for Neuroscience (CNS), IISc.

In September, they launched a research tie-up called Visual Neuroscience for Cybernetics. CynLr contributes the robots and real-world problems; Arun’s Vision Lab supplies the brain science. The partnership will also fund PhDs, set up training programmes, and give young researchers an avenue to enter applied robotics.

The goal is to combine brain science with robotics in ways that could revolutionise automation in everything from manufacturing to healthcare and maybe even harvesting coconuts.

On a factory floor, it means a robot that can grab a screw, a cap or a wire it’s never seen before and place it exactly where it belongs, with no custom training needed. One robot could perform multiple roles.

“Robots today suffer a lot to perform autonomously without prior training,” said Gokul, adding that robots do not have the “thinking capability” that they are supposed to have.

Apart from its Bengaluru office, CynLr has a design and research centre in Switzerland — Gokul calls the international expansion a response to India’s brain drain and “casting a net to catch them all”. The company has 60 employees today, expects to cross 100 soon, and is working toward its mission of building “one robot system per day”.

Last November, it raised US$10 million, and earlier this year, the World Economic Forum counted CynLr among its ‘Technology Pioneers’, a programme whose alumni include Google, Dropbox, and PayPal. WEF described CynLr as a company enabling manufacturers and logistics providers to build “fully automated” factories. Industry is paying attention too: CynLr’s first clients include Denso and General Motors.

For robots to use their vision and act on unknown objects is a large gap. And only when you fill that gap, what we call on-the-fly learning, can the system learn as it does the task

-Gokul NA, CynLr co-founder

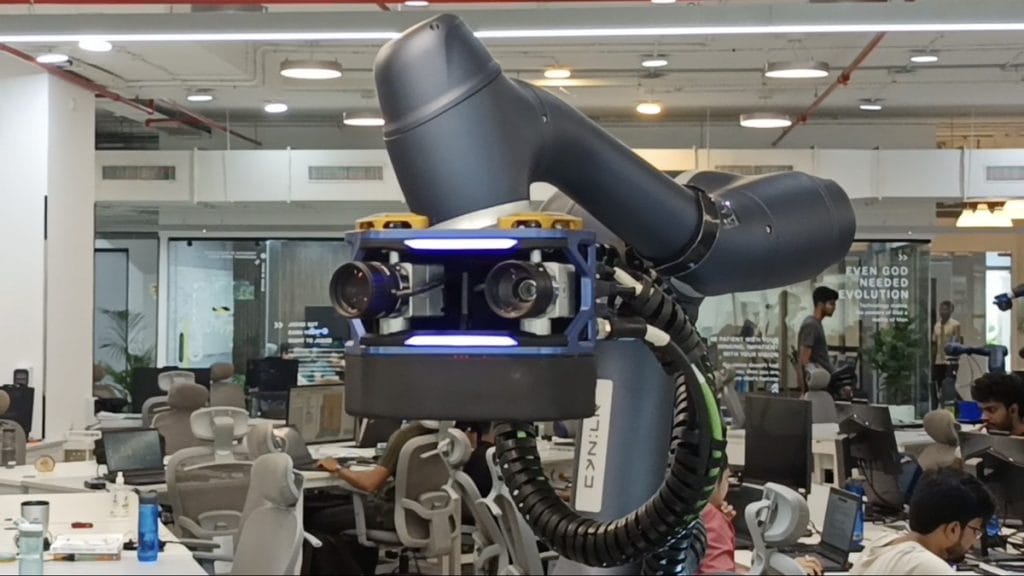

Their flagship creation is CyRo — a robot with two arms and a pair of eyes, designed to pick and drop objects it has never seen before. It was also presented at the United Nations AI for Good Summit. For Gokul, the accolades are only a push towards CynLr’s dream of making robots handle objects as effortlessly as humans do, especially with the IISc team now in the mix.

The tie-up began serendipitously. Arun had been exploring questions about vision beyond humans when a friend introduced him to Gokul. The two then decided to collaborate on computer vision—a branch of technology governed by AI models training computers to make them understand and collect data about images.

“(CynLr) wants to learn how the human brain solves vision tasks, and implement those learnings in robots. That’s how we got started discussing what we could do,” said Arun, who has an entire lab dedicated to vision at CNS-IISc.

It’s a steep curve. Labs that have tried to wire brain science into robotics have had only limited success.

In 2023, the EU wrapped up its Human Brain Project after 10 years, €600 million spent, and 500 scientists involved. It made progress in mapping the brain, but fell short of its goal of simulating one. One of its showcase robots was WhiskEye, fitted with whisker-like sensors to probe its surroundings and recognise simple objects. A breakthrough, but also a sign of the distance to be covered.

“Robots with a traditional computational architecture are still struggling with object manipulation, naturalistic movement and other tasks that would be intuitive for us,” said a Human Brain Project blog.

While neuro-inspired robots have surfaced in the news with blue-sky demos —like a robotic arm that ‘feels’ pain—getting such systems to actually work in industrial settings is an uphill task.

“In artificial intelligence as of today … there is nothing human-like about it.

Not even in the way it’s structured. And this new field called neuro AI is trying to bridge both — taking core principles from neuroscience of how the brain actually processes things, where both sides will benefit,” said Nikhil Prabhu, a cognitive neuroscientist in Bengaluru.

Also Read: Belagavi to Boeing. Karnataka aerospace hub is a shining postcard for Make in India

Fly on the wall

At each desk at CynLr’s office space, engineers are training CyRo. Near these machine-arms are computers that track how well the robots can comprehend objects placed in a tray, including bottles, clips, and keychains.

The challenge for CyRo is to go beyond its training set and handle objects it has never seen before. That learning curve determines how close it comes to behaving like an efficient machine.

It takes about ten seconds for CyRo to scan its surroundings with its dark, camera-like eyes. Then, with one huge arm, it picks up an object from the tray and drops it into a nearby basket. Behind their screens, engineers watch a visualisation of how the robot “sees” and interprets each shape.

A lot of the challenges of today’s neural networks is that they have ended up learning some weird things. And so when you come down to detecting a cup in the real world, just a simple change in the background colour can make a big difference to the ability of the network to detect a cup

-SP Arun, Professor & Chair, CNS-IISc

“Today, in spite of the progress we have made in machine learning, if I have not trained the robot on that picture of that object before, it cannot act on that. And the object looks different in different orientations which means it’s completely unfamiliar (to robots),” said Gokul.

For instance, in a factory, when robots are presented with millions of objects of different sizes and shapes, the chances are high they will baffle and behave maladaptively.

“So for robots to use their vision and act on unknown objects is a large gap. And only when you fill that gap, what we call on-the-fly learning, can the system learn as it does the task,” Gokul said.

Last year, CyRo was validated at the Robotics Summit & Expo in Boston, where it successfully handled unfamiliar objects in different lighting settings. Buoyed by that reception, CynLr now wants to prepare “paradigm-shifting” robots that can be deployed anywhere on the factory floor. The robots in the coming “CyNoid” series, Gokul said, will all look identical but can adapt to different needs simply by changing the software.

To help crack this futuristic vision, the lab is getting help from simians.

Monkeys and machines

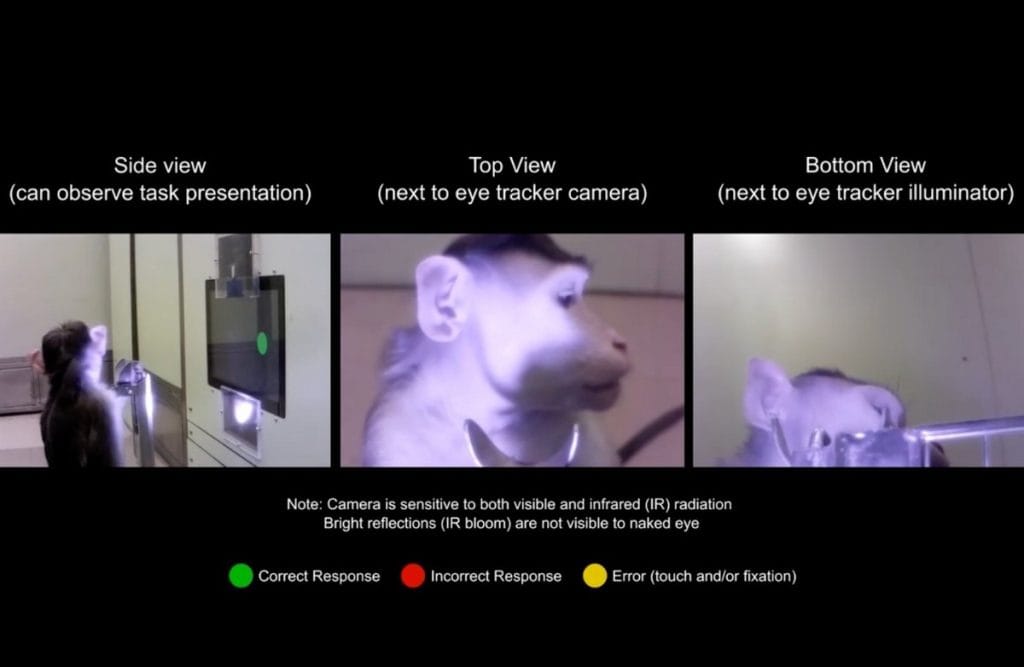

At Arun’s VisionLab, monkeys in large cages are presented with new objects and allowed to fiddle with them while their neural activity is recorded.

As in humans, their eyes can recognise an object even when it looks different from another angle. At the lab, the neural signals at each viewing stage are recorded and analysed.

The partnership between CynLr and VisionLab is currently focusing on how robots can pick up objects of arbitrary shape.

“We know from our investigations on the vision science side that when your eyes look at something, they naturally extract its shape. Perhaps we need to learn from how the visual system is representing and processing information—and by using those methods, you can have a robot that handles any shape,” said Arun.

What we want to do is… come up with a detailed process of what is happening from the initial stage to the end stage [of vision processing in the brain], and figure out how we can use this information to create algorithms for robots

-Sini Simon, PhD candidate at CNS-IISc

The team is combing through existing research on human visual processing as well. The aim is to answer questions such as: when animals interact with objects, how does the brain represent this information? How would this information be used in the brain?

“This would provide some insight that CynLr can integrate into their robotics research,” said Sini Simon, a PhD student at Arun’s lab.

As Simon pointed out, at present people who work in vision processing tend to study different aspects in silos.

Here, however, they’re working to map the entire process end to end — and then turn that map into code potentially for CynLr’s robots.

“What we want to do is to go through all this information and come up with a detailed process of what is happening from the initial stage to the end stage [of vision processing in the brain], and figure out how we can use this information to create algorithms for robots,” Simon added.

‘Dumb robots’ & new pipeline of researchers

Computers can crunch numbers at speeds humans will never match. Yet the human, or even monkey, brain and body still outperform them at tasks as simple as twisting a screw into a hole or putting a cap on a bottle.

What seems simple for us can be near-impossible for a robot unless it has been intensely trained on the exact same object.

Robots flounder in such tasks because of the way AI is conventionally trained, according to Arun.

For instance, a computer might treat a white cup with a blue background as a different object when it’s in a red background.

“A lot of the challenges of today’s neural networks is that they have ended up learning some weird things. And so when you come down to detecting a cup in the real world, just a simple change in the background colour can make a big difference to the ability of the network to detect a cup,” Arun explained.

Researchers have been trying various workarounds. A study in Frontiers in Robotics and AI five years ago, for instance, suggested that changes in brightness in training data could make object-recognition systems more robust.

However, the study emphasised that the method only works for small-scale computation and not complex tasks.

Even after years of research, recognising a “simple” object comes with “high demand for computing resources and increased computational costs with high dimensionality,” noted a 2024 paper in Neurocomputing.

With the new collaboration with IISc, CynLr is hoping to tackle these thorny questions in robotic vision by training next generation of researchers through PhD programmes and a coursework-based curriculum.

Such industry-academia fundamental research is largely absent so far, according to Gokul. The idea now is to build the missing bridge between lab findings and real machines.

“So, it matters that we focus and invest into the space, co-collaborate, and then build an academic partnership,” he said.

Also Read: India’s 1st commercial quantum computer has a task. Drug development

Factories and policy in need

Every year CynLr’s hiring team painstakingly sifts through 15,000 applications to pick just 15 skilled candidates across hardware and software roles.

But selection is just the start. New hires still need to undergo a year-long training programme before they are industry-ready, despite holding graduate degrees.

“You also have a problem of lack of global-grade MS and PhD programmes in India. Rarely are there institutions like IISc,” said Gokul. It is partly to find the right talent that CynLr has set up offices abroad at Prilly in Switzerland and Texas in the US.

At the company’s Bengaluru office, the boardroom often doubles as a training ground.

“The first biggest issue is that we are trying to build a car, but what’s available are cycle wheels,” said Gokul. While aspirations are high, the supply chain in India is basic and not suited to the robotics industry.

For now CynLr relies on an “extensive supply chain” of over 400 parts sourced across 14 countries, according to its website.

The science problem that we solve is not an unexplored problem. It’s an unsolved problem

-Gokul NA, CynLr co-founder

In India, there are challenges at various levels. Infrastructure, ecosystem, and policy all fall short, and deep-tech research like this receives indifference from both government and academia, according to Gokul.

“The know-how from a hardware point of view is yet to evolve in India. Lack of a competitor is also a challenge. If the competitor is actually there, there is an industry that is being created,” he said.

Robotics, he argues, is not treated like its own domain by the government, unlike, say, space, where the existing infrastructure runs like a well-oiled machine.

“That is not available for us. The science problem that we solve is not an unexplored problem. It’s an unsolved problem.”

Sitting in the training-cum-meeting room, Gokul recalled the buzz in 1960 about robotic arms as the next generation of factory workers in America. General Motors, the first company to install a robotic arm back then, is now a CynLr customer. Yet GM still struggles with the scale of modern vehicle assembly, where a platform must handle more than 20,000 parts, co-founder Ramaswamy said in an Economic Times article. He added that CynLr’s CyRo platform is being designed to meet such demands

The full automation dream is still unrealised, Gokul said, partly because of snail-paced government policies when it comes to carving out a deep-tech ecosystem.

Nonetheless, CynLr’s partnership with IISc offers some hope of opening doors in robotics. Maybe not to serve a Coke but to at least tighten a screw.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)