Belagavi: An airplane’s parts travel around the world even before the aircraft itself is made. That’s how fragmented aircraft manufacturing is. But Hubli boy Aravind Melligeri had a dream in 2007. He wanted to build aircraft components, such as doors and engine spinners, in a single place, from raw material to finished parts.

Within 500 metres, to be precise, instead of the typical 5,000 kilometres.

He did consider tier-one cities for the venture, but his heart anchored the entrepreneurial dream to Belagavi, near his hometown Hubli. Today, his aerospace hub is a shining postcard for the Make in India mission. From doorstops to engine spinners, his company Aequs now manufactures components for aviation behemoths like Airbus and Boeing, making Belagavi India’s first notified aerospace precision manufacturing Special Economic Zone.

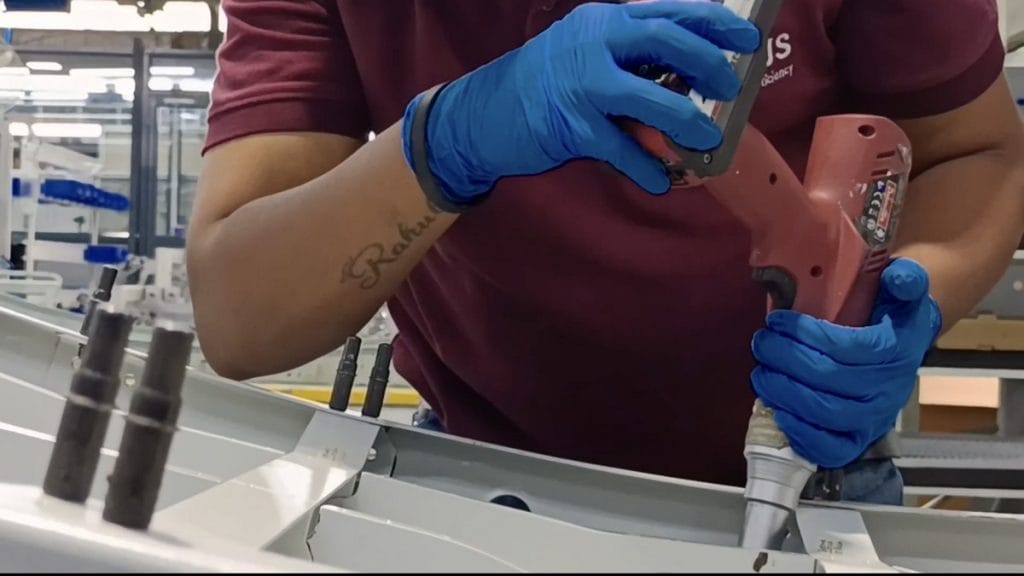

With workers, engineers, and imported machines, Aequs runs almost round the clock. In one large space, a single operator controls a batch of machines with just a few button presses.

“Bringing it all together in such a short period of time in a small area reduces the carbon footprint and speeds up the whole process. We can do everything (end-to-end manufacturing) in 24 hours and ship parts to customers,” said Aravind Melligeri, chairman & CEO of Aequs, in his Belagavi office. It’s built on land, he recalled, that was barren less than two decades ago.

Globally, the aerospace industry is inching towards a Mayday. As seasoned engineers retire, companies report production delays and quality concerns.

In 2023, 75 per cent of European manufacturers gave an SOS call regarding the aging crisis in the industry.

Asian countries, and India in particular, see an opportunity in this demographic panic in the West. India’s edge in the manufacturing industry is its army of potential workers, with about 15 lakh engineering graduates every year. In sheer numbers, this gives India an edge over both the United States and an ageing China.

“What we did initially was decapitalisation,” Melligeri added—investing less in capital, and more in labour, as long as “the same quality” could be delivered.

But a large number of people with degrees alone don’t solve the problem. Of the 15 lakh engineers graduating each year, only about 2.5 lakh land jobs, underlining the need for more jobs as well as upskilling.

At the end of the day, with all the technology, you cannot scale if you don’t have the skilled people. That is where we invest more time

-Rajeev Kaul, managing director, Aequs

To meet this gap, Aequs is investing in upskilling a hefty talent pool to meet global demand. The Indian aerospace manufacturing industry, too, is expected to boom in coming years, with Karnataka and Hyderabad hosting the most companies, including Hindustan Aeronautics Limited, Tata Advanced Materials, Mahindra Aerospace, Dynamatic Technologies, Safran Aircraft Engines, and Azad Engineering.

“Our industry is very well integrated with the world. With India ordering so many planes from Boeing and Airbus, we have to take advantage of technology transfer and ensure that the component supply base comes here. This is the time to build that ecosystem,” said Gunjan Krishna, Commissioner of Industries and Commerce, Government of Karnataka, who has closely observed the capacity of Aequs alongside other manufacturing companies in the state.

Still, some experts argue India needs to rethink its education system to build a truly efficient manufacturing industry so that it doesn’t miss the flight when compared with Asian counterparts such as China.

Also Read: India’s 1st commercial quantum computer has a task. Drug development

A forging-to-flight hub

In a 40-feet-high building, a 16-feet hydraulic press crushes an aluminium block with a force of 10,000 tons. The hall absorbs the shock so completely that only a low hum fills the air.

This is where Aequs, through a joint venture with Aubert & Duval Engineering, forges material for doorstops, windows, and engine spinners for aircraft such as Airbus. The facility now achieves 100 per cent in-country value addition. From raw material to a shaped product ready for machining, everything happens in India.

Just a few years ago, an aircraft door, for instance, would have circled the globe—collecting raw material from one country, shaping in another, assembling it in a third. At Aequs, the forged block now travels just half a kilometre, across the road to the machining facility. Here, workers with around 70 machines fine-tune the parts.

“These machines are programmed to cut material into the shape and form you want. When a drawing comes from the customer, our engineering team looks at it and writes the process to achieve the final shape,” said Melligeri.

At times, one worker operates four machines, going through various stages such as loading material, monitoring the process, and retrieving the finished piece.

But this is just a slice of Aequs’ capability. A few hundred metres away, the company runs an automated facility launched in 2018—the pride of the company. Like a washing machine, material, such as a block of aluminium, is loaded once and left to the rows of machines that process it in multiple steps without any human involvement.

“Machines are sculptors here,” said Melligeri.

But precision alone is not enough. Aircraft parts must survive extreme changes in pressure, and weather up in the sky. Parts need a fitness test and treatment to withstand any atmospheric torture while in flight. That is the task of Arunkumar KS, operations head at Aerospace Processing India Pvt. Ltd. (API), a joint venture between Aequs and Magellan Aerospace.

Just opposite the machining facility, Arunkumar and his team work in shifts to put parts through a vigorous testing and coating process.

“We started in 2008. At that time, we were the first in India to have a surface treatment facility, and today we are India’s biggest,” Arunkumar said. His team examines parts repeatedly for defects at every stage, whether it’s after forging or machining. According to Arunkumar these tests are done without disturbing the parts, called non-destructive testing.

“If any defect is found, we identify it and throw it out,” said Arunkumar. In aerospace manufacturing, there is no room for even the slightest error.

With India ordering so many planes from Boeing and Airbus, we have to take advantage of technology transfer and ensure that the component supply base comes here. This is the time to build that ecosystem

-Gunjan Krishna, Karnataka Commissioner of Industries and Commerce

These stringent quality checks have earned Aequs the trust of companies such as Airbus and Boeing. Now the leadership is planning to scale production to compete with global companies. But the aerospace manufacturing supply chain is complicated, and India currently accounts for only 2 per cent of it, according to Melligeri.

“In the next fifteen years, we are going for a 10 per cent jump. Our goal is to get 10 per cent of the global supply chain into the country,” Melligeri said.

Earning trust, part by part

The mass production of an aircraft part is relatively simple when compared with procuring an order and winning a customer’s trust. It begins with dialogue between Aequs engineers and the client, while the leadership demonstrates the company’s capacity.

At this stage, the company presents drawings and materials to outline the costs and, if all goes well, secure a contract. After this, raw materials are procured and the first samples are produced.

This stage is the most challenging, according to Nagesh HR, vice president at Aequs. Engineers must verify the cutting tool path, optimise it, and also figure out the right technology.

“Suppose you have a cake and you have to cut it into a number of pieces. Obviously, you’ll look at it to find what is the minimum wastage you can do,” Nagesh said. “If you’re using the right tool, path, and strategy, only then will you have an optimum process. Otherwise, you can cut, but how many hours might you take?”

The inspection process is even more exacting. For instance, a single aircraft door may have more than 2,000 holes, each one inspected by engineers for precision. Every measurement and detail is recorded and stored: who made the part, where it was made, who inspected it. Each component has its own family tree.

Let alone inspection, each machine, worth thousands of dollars, needs a workforce trained specifically to operate it.

“At the end of the day, with all the technology, you cannot scale if you don’t have the skilled people. That is where we invest more time,” said Rajeev Kaul, managing director of Aequs.

Also Read: Indian scientists, entrepreneurs are trying to understand chronic pain. Finally

Banking on Indian youth

Six days a week, Sagar Bairewadi rides his motorbike 6 kilometres from his home in Belagavi to the Aequs plant, where he works as a technical assistant. He found his footing in aerospace manufacturing through the company’s training programme.

The B.Sc graduate from Rani Chennamma University in Belagavi has picked up brand-new skillsets— such as sand blasting—through rigorous hands-on training.

“The training (in Aequs) is different. It’s a very good environment inside. They have supported us and they trained us very well,” said Bairewadi, who has worked here for two years and is no longer a rookie in the aerospace manufacturing industry.

Most of the people who work at Aequs are from within 30 kilometres of the manufacturing hub. Melligeri’s mission was to tap local talent and open job opportunities around Belagavi.

“We had people who joined us very early on from the US and UK to help us and teach others,” Kaul said.

People-centric development for manufacturing in India is way behind. We have a university education system, but manufacturing is not taught the way it is taught in Taiwan, Korea, China

– Roy Mahapatra, professor of Aerospace Engineering, IISc

At first, the hired diploma graduates from Belagavi were given intense training on how to handle million-dollar machines. Aequs also teamed up with engineering colleges in other parts of Karnataka.

In 2018, it started an on-campus internship programme with Karnatak Lingayat Education Technological (KLE Tech) University in Hubli. Students from as far as 100 kilometres arrived to be trained on aircraft component manufacturing skills. They were also taught how to solve supply chain problems.

“About 50 to 60 per cent of the students got a placement in Aequs. The rest got into other industries because of the kind of training (they received at Aequs),” said BB Kotturshettar, dean of Mechanical Engineering, KLE Tech.

Across north Karnataka, Aequs has taken interns from institutions such as Gogte Institute of Technology, Jain College, and SG Balekundri Institute of Technology.

“Over the last two years we have taken 110 such interns who are typically in the last year of their BE course and need to complete specified months of internship,” the company confirmed in an email.

At the same time, Aequs hires apprentices from some 17 graduate colleges and polytechnics in and around Belagavi. Currently it has 160 apprentices on its rolls, most absorbed into the workforce after completing on-the-job training.

“We have a programme in the final year where they come (as an intern), and they work here, and they go back. In fact, we have a master’s in aerospace manufacturing in one of the institutes here in Belagavi,” Melligeri added.

Some unlearning is also part of the process. According to Kaul, with more machines coming into Aequs, the workforce will have to forget conventional ways of working and upskill to work alongside automation—rather than worrying about losing their jobs to machines.

In the next fifteen years… Our goal is to get 10 per cent of the global supply chain into the country

-Aravind Melligeri, Aequs CEO

But academics warn that to meet global standards, India must invest more in manufacturing education rather than simply adapting overseas learning models.

“People-centric development for manufacturing in India is way behind. We have a university education system, but manufacturing is not taught the way it is taught in Taiwan, Korea, China,” said D Roy Mahapatra, professor of Aerospace Engineering at the Indian Institute of Science (IISc).

Industries often have to spend months training new recruits despite their degrees, according to him. This, he added, explains why the manufacturing industry is keener to hire senior secondary-level diploma holders rather than engineering graduates.

Mahapatra said that in India’s universities, manufacturing is taught mainly as the use of imported machines. Domestically, “there is no focus on building manufacturing machines”.

To grow its share of GDP from manufacturing, India needs to export technology rather than just products.

“We as a country are lacking abilities to create machines,” said Mahapatra. The next frontier, he added, will be software-centric technologies for manufacturing, where AI will play a central role.

Aequs is already planning to integrate AI into its production lines to deliver products more efficiently, according to Kaul.

Mahapatra, Melligeri, and Kaul stressed alike that aerospace is a slow-growth industry that demands long-term strategy. That is why Melligeri launched Aequs with a thirty-year vision instead of pursuing quick returns on investment.

“There is no better platform in India today to come and experience all these capabilities. So we continue to invest because the people are available. We bring that on-the-job training. Only when you actually touch and feel you will actually do it,” Melligeri added.

Each day near sundown, a fleet of buses carries workers from the vast 250-acre facility back to their homes—men and women who spend long hours manufacturing doors and engine spinners for world-famous aircraft that may never touch down in their hometown.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

According to the honourable Leader of Opposition, Mr. Rahul Gandhi, and his lackeys – Jairam Ramesh and Mallikarjun Kharge, Make In India is a flop show. It is an absolute failure.

Maybe the reporter can cross check with them regarding this “story”.