Kashmir: Mohammed was cycling home from college when someone suddenly shouted, “Mirzayi aav” — the Mirzayi has come. Moments later, two sticks wrapped in barbed wire slammed into his back. He dropped his bicycle and ran.

His crime: being an Ahmadiyya, or Ahmadi.

“To reach my home, I had to pass through a neighbourhood where non-Ahmadis lived. After the attack, I didn’t attend college for two weeks, until we found a new route home,” said the 27-year-old. His voice still trembles when he speaks of the incident, which happened in 2016. Today, Mohammed is a professor at a college 40 km from his village. He lets everyone think he is a Sunni. It’s a question of safety.

Branded heretics by many Sunnis, Ahmadiyyas have become a shorthand for Muslim-on-Muslim persecution. In Pakistan, they can be jailed for calling themselves Muslim, or attacked for their ‘blasphemous’ belief that sect founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad was a prophet. In Bangladesh, their mosques have been torched, books banned, gatherings mobbed. In India, it’s more subtle. Officially, Ahmadiyyas are recognised as Muslims, but in Kashmir, they are boycotted and shunned.

Shops and schools turn them away. They’re mocked as “Mirzayi” or “Qadiani”—slurs derived from the name of sect founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, and his birthplace, Qadian in Gurdaspur, Punjab. In village mosques, maulvis openly demand they should ‘go back’. Community members say these calls grow louder during Friday sermons, especially in mixed neighbourhoods. At one sermon in the suburbs of Srinagar two years ago, loudspeakers blared: “Qadiani leave Kashmir. Go to your Punjab. Don’t infect our Muslims with your non-Islamic ideas. You are kafirs.”

Other Muslims treat us like untouchables—just like Dalits are treated in Hindu society. When we walk down the road, and if they catch a glimpse of us, they spit on the ground

-60-year-old head of an Ahmadiyya mosque

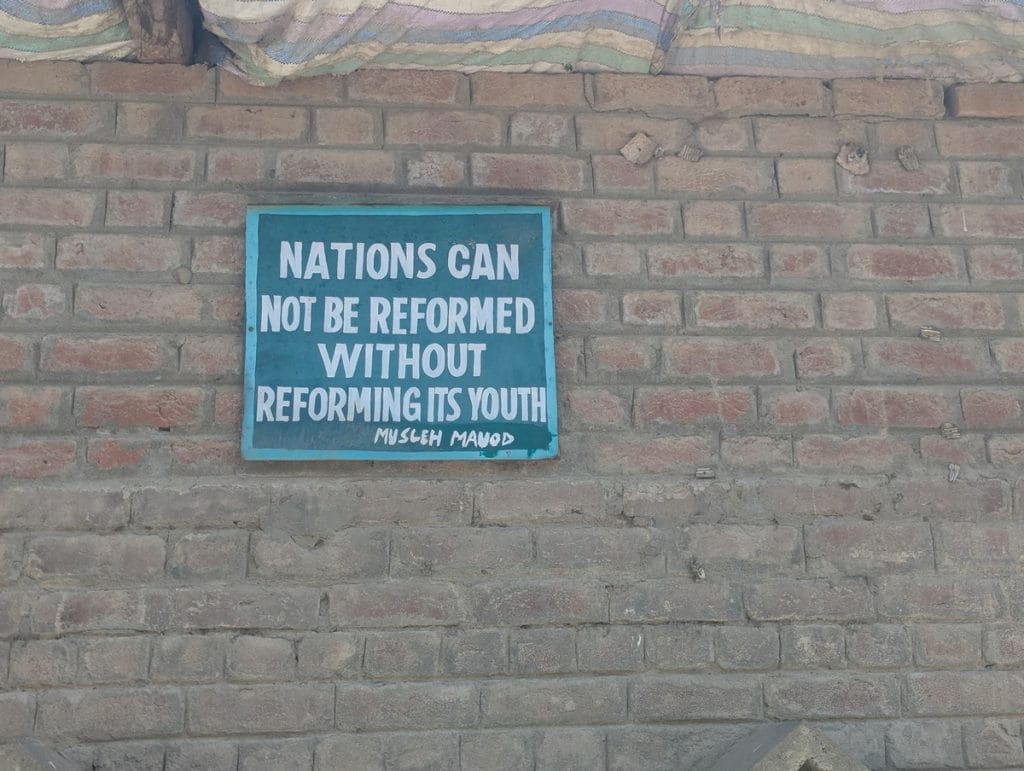

Ahmadiyya clerics estimate their population in the Valley at 15,000. Most live in small, isolated pockets. In mixed areas, many conceal their faith. Over the years, they’ve built their own parallel systems—schools, mosques, and shops. Their slogan, Love for all, hatred for none, is painted inside these buildings but never said outside. In universities and workplaces, they often try to pass off as Sunni. With their small numbers, they are not even a vote bank for Jammu and Kashmir’s political parties. They are voiceless, invisiblised, and ignored.

The level of hostility has fluctuated over the decades, deepening in the 1990s as militancy spread.

“Before the 1990s, Ahmadiyyas and non-Ahmadiyyas would even intermarry. Relationships were cordial. But everything changed when the Jamaat gained influence in Kashmir. They began to control the corridors of power. Political parties started appeasing them,” said an octogenarian Ahmadiyya cleric.

While the BJP coming to power at the Centre diluted the Jamaat-e-Islami’s influence and the outfit was banned in 2019, many Kashmiri Muslims still treat Ahmadiyyas with suspicion and disdain.

“It’s less violent but the boycott, discrimination, and hatred still remain,” the cleric added.

Ahmadiyyas in Kashmir are quick to stress their loyalty to India. They’ve never backed the Azadi movement, they say, and not one from the community joined the militancy, even at the peak of the insurgency.

Also Read: Kashmiri Sikhs ask how to stop losing daughters to Islam— ‘It’s a threat to demography’

Hiding in plain sight

Noor is 12, and her religion weighs on her. Her best friend is a Sunni Muslim, and she doesn’t want to lose that friendship. Even if it’s one where she can’t share who she really is.

“We’ve been friends for eight years. She thinks I’m a Sunni. And I don’t challenge her illusion,” she said, rubbing her fingers nervously.

It’s the second day of Eid-ul-Adha, and Noor has just got off a half-hour call with her best friend. She showed her new clothes on video call and giggled. Tomorrow, she will take a naat phol (piece of meat) for her. She wants to take the best, most succulent cut.

But a fear haunts her: “What if they find out who I really am and stop talking to me?”

The feeling of being different pinches her from the inside. Every day, Noor travels one and a half hours to reach her school in Srinagar. She can’t attend the schools nearby because everyone there knows she is an Ahmadiyya.

In the city, wearing her school shirt and skirt, she blends in. She never tells them. They never ask her.

She has learned from her elder brother’s mistake. In 2019, when he was studying at college in South Kashmir, he shared a rented accommodation with three friends. One evening, during a warm heart-to-heart, he told them he was an Ahmadi. By nightfall, they had packed their bags and left. Six years later, said Noor, her brother is yet to move past that humiliation. Her parents, both government employees, are careful never to mention their religion at work.

Elsewhere in Srinagar, Isfhaq had to withdraw his two sons—aged 11 and 15—from school last year after some friends saw them entering the Ahmadiyya mosque, located beside a police camp in central Srinagar.

“They started asking my children what they were doing at the kafir mosque. My children came back home, and I advised them to reveal their identity the next day. And they did.”

The news spread like wildfire across the school. Students and teachers alike started avoiding them. Their friends would no longer talk to them.

After the 1990s, some Islamic muftis began openly speaking against [Ahmadis], embedding them even deeper into a narrative of exclusion. They became a victim of the larger Islamisation discourse

-Aejaz Ahmad Rather, a Kashmiri PhD scholar from JNU

Now, the boys study in a school run by a non-Muslim.

“They’re doing fine there. The principal knows they are Ahmadiyyas but doesn’t discriminate,” Isfhaq said.

Back at Noor’s two-storey house, where the small garden is abloom with roses, her grandfather asks for all five grandchildren to gather. Wearing a grey pathan kurta, standing upright, he places his right hand over his chest.

“Hum Ahmadiyya hain. We are not criminals. We should not fear. Hide your identity, but if they find out, be patient. Listen to whatever bad they say. Patience is our only defence. Patience is what Allah teaches us,” he said in his rasping voice.

His audience, aged between 8 and 22, nods silently.

For the community, there is no other choice. Their past has taught them a bitter lesson: it’s easy to lose everything, even in places that once promised protection and belonging.

A piece of their history still haunts them: their key role in the movement leading to the formation of Pakistan, once imagined as a promised land. That same country has itself unleashed blatant attacks on their community.

Pro-Pakistan once, now loyal to India

Ahmadiyyas in Kashmir are quick to stress their loyalty to India. They’ve never backed the Azadi movement, they say, and not one from the community joined the militancy, even at the peak of the insurgency.

But a piece of their history still haunts them: their key role in the movement leading to the formation of Pakistan, once imagined as a promised land. That same country has itself unleashed blatant attacks on their community. It declared them non-Muslims in 1974, banned them from praying publicly, and criminalised their very identity.

Ahmadiyyas in Kashmir often try to distance themselves from their earlier allegiance to Pakistan. Some describe it as a compulsion born out of the acute communal tensions ahead of Partition in 1947.

Ironically, the hostility they are subjected to in Kashmir today also has a Pakistan link: cross-border militancy and the spread of hardline Islam.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, as militancy took root in Kashmir, the region’s religious landscape began to shift.

“Islam became more orthodox and radical,” said a senior scholar from Kashmir University, requesting anonymity.

Around this time, Kashmir’s Sufi traditions had started giving way to a more rigid Islam. Conservative clerics became more influential and young men began “adopting Arabic-sounding monikers”, wrote veteran journalist Tariq Mir in a Pulitzer Center paper, Kashmir: From Sufi to Salafi.

Mir added that by the early 2000s, the Indian state had used force and diplomatic pressure to bring down the insurgency. “But militant Islam took root in the cultural landscape.”

Among Muslims, the Ahmadiyya community became the first casualty as radical Islam became more entrenched. Like in Pakistan, they were labelled kafirs and erased from mainstream religious life.

“After the 1990s, some Islamic muftis began openly speaking against them, embedding them even deeper into a narrative of exclusion. They became a victim of the larger Islamisation discourse,” said Aejaz Ahmad Rather, a Kashmiri PhD scholar from JNU, who has done research on the community for his dissertation, Ahmadiyya: The Making of Identity in Colonial Punjab.

Their response has largely been to retreat inward.

“The Ahmadiyya community in Kashmir feels segregated from the mainstream and faces systemic discrimination. As a result, they remain closely connected with each other. Their community is tight-knit and organised,” he added. “Until now, they have faced repression silently and have not spoken out about these issues.”

Unlike the invectives often directed at them, Ahmadiyya Friday sermons promote interfaith respect. “It does not endorse hatred, violence, or have political elements,” said the octogenarian cleric.

Invisible walls

It’s Eid, yet outside Noor’s house, a row of cramped, forlorn shops sees only a trickle of customers. The grocery store, salon, and chemist’s shop here cater solely to the two dozen or so Ahmadiyya families that live in the neighbourhood.

Just beside the shops, a narrow lane leads to an Ahmadiyya mosque, their school, and about 30 homes. This is a mixed locality on the outskirts of Srinagar, where Ahmadiyyas live a life shadowed by quiet boycott. Within this shared space, they remain ghettoised and excluded.

This ghettoisation became more pronounced eight years ago, when a young boy from the community went to buy a packet of chips from a non-Ahmadiyya shop. He was kicked out and verbally abused. The next day, non-Ahmadiyyas approached government officials, demanding separate ration cards for the Ahmadiyyas. Soon after, the community set up its own shops.

“Other Muslims treat us like untouchables—just like Dalits are treated in Hindu society,” said the 60-year-old head of an Ahmadiyya mosque. “When we walk down the road, and if they catch a glimpse of us, they spit on the ground.”

This “untouchability” isn’t just rhetorical. Like with Savarna Hindus and Dalits, it’s tied to ideas of purity.

Two years ago, Mohammed’s brother entered a non-Ahmadiyya mosque in South Kashmir. After someone recognised him, he wasn’t just thrown out—the mosque was washed with detergent.

A sip of water, then fire

It was a non-Ahmadiyya wedding in 2012, and 26-year-old Iqbal had been invited. Though slightly nervous, he attended. He was the only Ahmadiyya there. About an hour into the function, after biting into a chilli, he rushed for water and drank from a tap attached to a black Sintex tank.

The next morning, that tank went viral. A group of village clerics and residents marched up to the tank, stuffed dry grass into its mouth, and set it on fire. One of the participants recorded the entire episode and shared it on YouTube.

“It was because an Ahmadiyya drank water from a Sintex tank that belonged to non-Ahmadiyyas,” Iqbal’s cousin said. “It was to teach the community a lesson.”

The video starts with a caption: “Sintex misused by Mirzai pasand (Qadiani) people was burned by Muslims in a village after Friday prayers in the premises of a Masjid.”

It was uploaded by one Shakeel Ahmad, who regularly shares videos of the cleric Mufti Manzoor Ahmad Qasmi. Several of these videos sternly advise women to adopt parda and urge Muslims to protect their deen (religion). Such new-age preachers, said an Ahmadiyya cleric at a mosque just outside Srinagar, are disconnected from Kashmir’s Sufi roots and have “intoxicated young minds with hate.”

This radical turn, said Mir in his paper, traces back to Saudi funding and the training of “hundreds of young men in the Islamist discourse…”

[Ahmadis in Pakistan] are not allowed to slaughter goats. Their mosques are burnt down. And they are killed in broad daylight with impunity as other Muslims support our bloodshed. Thank god, we are in Hindustan

Qazi, an Ahmadiyya resident of Kashmir

In 2014, local Sunni clerics declared all intermarriages between Ahmadis and non-Ahmadis null and void. According to Ahmadiyyas, the discrimination intensifies every time a radical maulvi visits a village for sermons.

In a video uploaded last year, a Friday prayer sermon by Mufti Mushtaq referred to Mirza Ghulam Ahmad—and by extension, Ahmadis— as “Dajjal” (false messiah).

“It was said there will be no Nabi after me [Prophet Muhammad]. But there will be a Dajjal who will claim prophethood. And the one who makes such a claim is a Dajjal, a liar. So it is established that the Mirzayi, the Qadianis—the Ahmadis—are against religion,” he declared.

Below the video, a commenter posting as “Beigh Bhai” wrote: “He is lying.” Someone replied: “Qadiani exposed. Dajjal.”

But unlike the invectives often directed at them, Ahmadiyya Friday sermons are tightly vetted and promote interfaith respect.

The speech is drafted in the UK, sent to the headquarters in Qadian, and from there forwarded to clerics in Jammu and Kashmir. They receive a printout and read it word for word.

“Few points are kept in mind before framing the speech. It does not endorse hatred against any community, violence, or have political elements. We have orders to stay away from politics,” said the octogenarian cleric.

Posts and prayers

Social media is the only place where Ahmadiyyas in Kashmir can speak freely, though even there they use pseudonyms.

Every day, 23-year-old Qazi replies to posts that call his community “lesser Muslims”, “kafirs”, or even “Hindus”.

“Please read religious literature before calling us Kafirs,” said one of Qazi’s replies. Another response read, “You are just misguided Muslims. I pity for you.”

Through Instagram, he stays connected with Ahmadiyyas across Jammu and Kashmir. Community elders also told ThePrint that they have married their daughters to Ahmadiyyas in Pakistan.

“Our community is very small. We don’t marry outside, or we won’t be able to sustain it. We’ve had our daughters marry educated Ahmadiyyas from Pakistan, but they don’t live there — they’re settled in the UK and Canada,” said an elderly man whose daughter was married into a Lahore-based Ahmadi family.

Ahmadis in J&K keep close tabs on the travails of their community in Pakistan.

“They are not allowed to slaughter goats. Their mosques are burnt down. And they are killed in broad daylight with impunity as other Muslims support our bloodshed. Thank God, we are in Hindustan,” Qazi said.

At the only Ahmadiyya mosque in Srinagar, adjacent to the police headquarters, congregants offered special Eid prayers for their community across the border.

Earlier this month, religious extremists, reportedly with the support of local authorities, prevented Ahmadis from offering Eid prayers and performing animal sacrifices in several Pakistani cities. In some places, forced conversions were also reported.

Quazi, too, prayed for them: “I asked Allah to protect them from the oppressors and the zulm (injustices) unleashed on them.”

The Ahmadiyya community has developed its own informal system of governance. In every village, there’s a council head and departments overseeing various aspects of daily life—from youth affairs to law and order.

‘Liberal, scientific, rational’

A male teacher is checking a notebook with a red pen when a 10-year-old student stops by the staff room. “Who are Ahmadiyyas?” he asks. Without a second thought, the teacher responds: “Liberal, scientific, and rational Muslims.” Then he tells the student to learn the meaning of those three words at home.

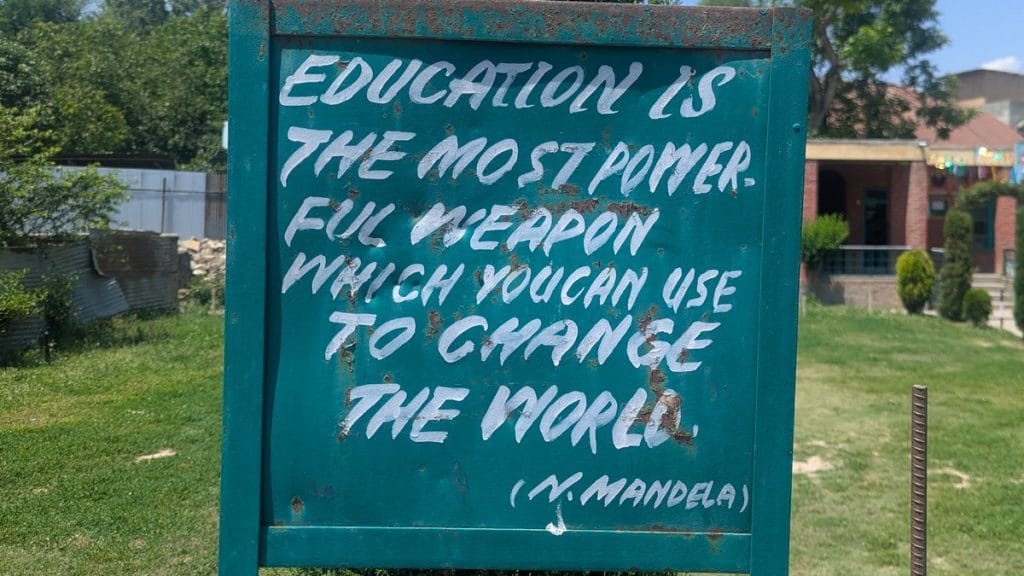

At this Ahmadiyya school on the outskirts of Srinagar, the red-brick walls are lined with posters of BR Ambedkar, Bhagat Singh, Kalpana Chawla, Shakespeare, the famed Kashmiri poet Mahjoor, and Pakistani theoretical physicist Abdus Salam—an Ahmadiyya who in 1979 became the first Muslim to win a science Nobel Prize.

At the entrance, a green iron board reads: “One child, one teacher, one pen and one book can change the world.” The plaque bearing the school’s name says “Government-recognized school”.

Only 80 students study here, but the school teaches a wide range of subjects, from skill development classes to Kashmiri, English, Urdu, and even Hindi, which is unusual for the Valley.

“Our students can go to other states and read Hindi, unlike many non-Ahmadiyya Muslim students. For us, Hindi is just a language that can help our youth assimilate into the wider society,” said a senior teacher who has taught here for over a decade.

To teach Hindi, the community hires Hindu teachers from the Jammu region, added the principal. Students are also encouraged to learn about other Muslim sects.

It’s not just schools. The Ahmadiyya community has developed its own informal system of governance. In every village, there’s a council head and departments overseeing various aspects of daily life—from youth affairs to law and order.

“These departments try solving issues on their own first, after getting council head in the loop. If the matter is precarious, we simply go to the police,” said the head of the Youth Department.

Community leaders maintain that education is the only tool to forge ahead. But not in Kashmir.

Shut doors and glass ceilings

Mohammed is a success story by most standards. He has two Master’s degrees, a PhD, cleared the National Eligibility Test, and is now teaching at a college. But when it comes to career advancement, he says, merit doesn’t matter.

“My sect comes in between,” he said with a bitter laugh.

Last year, he applied for an assistant professorship at a prestigious J&K university, but claims his application was rejected after someone in the administration flagged his Ahmadiyya identity during background checks.

On the second day of Eid, his house looks like any Kashmiri Muslim household. The remains of slaughtered goats are being chopped under a makeshift open tent in the garden. There are men in pathan kurtas, women in new bangles and Pakistani suits, and children running around with their eidis.

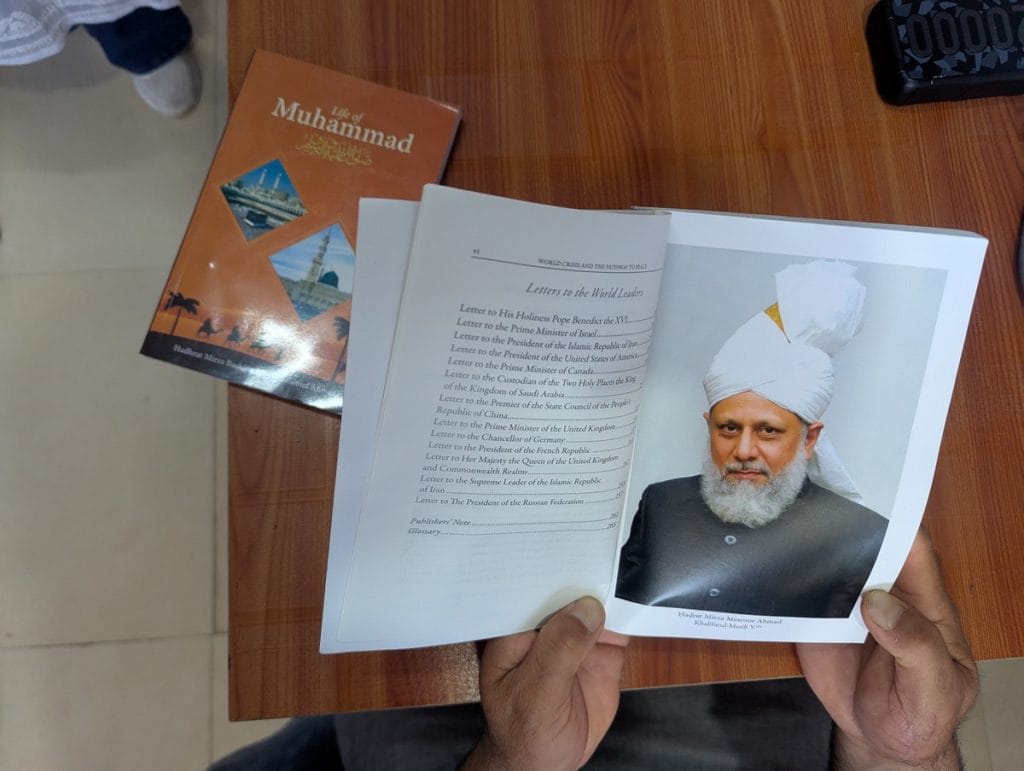

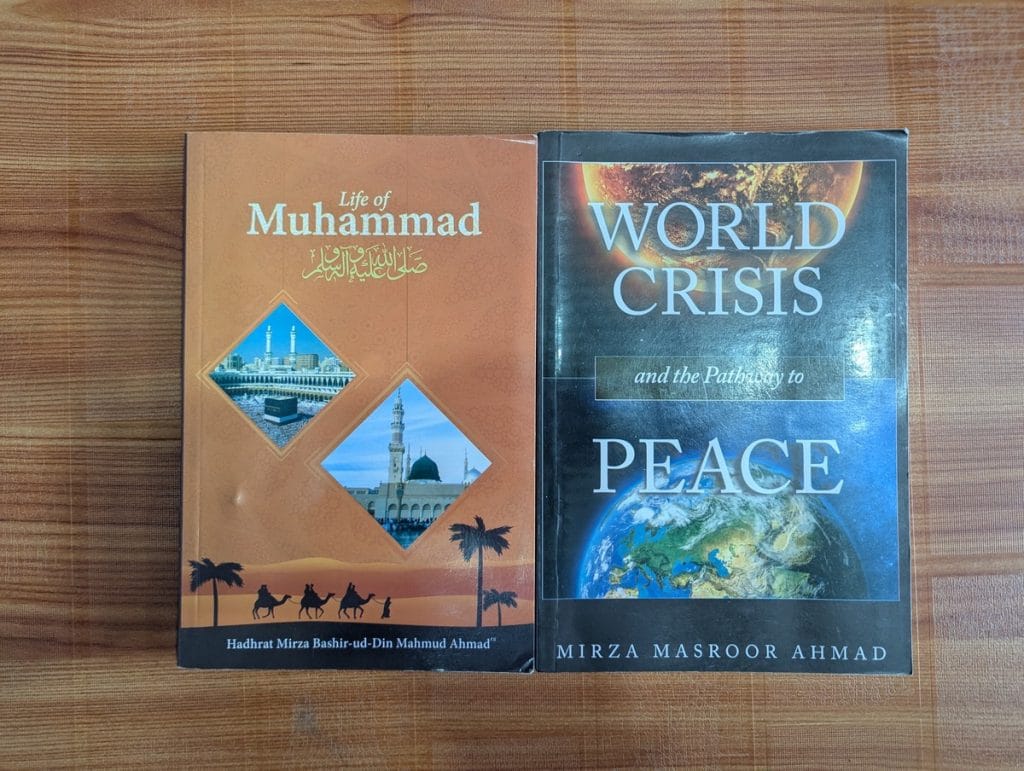

But in his room at the far end of the house, Mohammed sits alone, reading World Crisis and the Pathway to Peace by Mirza Masroor Ahmad, the spiritual head of the worldwide Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. Reading this 263-page book is his personal Eid ritual. He says it helps him “re-learn the teachings of Islam”.

He recites one of the passages aloud. It’s about how Ahmadis living in Great Britain are extremely loyal citizens “because of the teachings of our Prophet who instructed us that the love of one’s country is an integral part of one’s faith.”

Mohammed pointed out that this lesson holds true anywhere: “An Ahmadiyya living in Hindustan will protect his land. And despite atrocities committed on them, Ahmadiyyas in Pakistan will protect their country,” he said. “We have been told by our Prophet that if you are in a war you fight for your country and not identity.”

But that spirit isn’t always returned.

In 2014, when floods ravaged many parts of Kashmir, Ahmadiyya clerics received donations for relief work from the Gurdaspur headquarters. Mohammed and other youth volunteers were tasked with distributing the aid. But when they knocked on doors, they weren’t always welcomed.

“Hardly half a dozen families took the relief,” said Mohammed. “Others, despite being in a precarious situation, shut doors in our faces.”

Over the years, several Kashmiri Muslim scholars and historians have written against the discrimination faced by Ahmadiyyas, but it has done little to effect a larger change in Kashmiri society.

Also Read: Kashmiri Pandits are reviving old hometown temples. ‘It’s how we will return’

Praying under cover

In the narrow lanes of Khanyar in Srinagar district stands a small shrine with grey marble walls and wooden doors and windows. This is the Rozbal shrine, an understated but contentious site that has deepened the divide between Ahmadis and non-Ahmadis.

It is dedicated to a saint called Yuz Asaf, but for Ahmadis, it is the final resting place of Jesus Christ. In writings from 1899, sect founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad claimed that Jesus survived the crucifixion, travelled east, and died in Kashmir. The theory got wider traction with German author Holger Kersten’s 2001 book Jesus Lived in India.

For many other Muslims, however, the belief that Jesus is buried on earth is blasphemous.

“These Ahmadis have turned this shrine into a big deal. It’s just a way to make money,” said a 70-year-old Sunni Muslim.

For the Ahmadiyyas, the site holds deep religious significance. They are asked by their religious leaders to offer namaz there at least once a year. But according to the octogenarian Ahmadi cleric, they’re denied entry if they reveal their identity. So they visit posing as Sunnis, and quietly ask God to forgive them for their deception.

They have fed this narrative that we are different so deeply that even as a Muslim in their mosques, I feel alien and I am not able to pray properly

-Mohammed, member of the Ahmadiyya community

Religious practice is fraught in other ways too, including access to institutional support.

Until about five years ago, several Ahmadiyyas from Kashmir were denied the government Hajj quota, community members allege. According to them, the committees handling Hajj in Kashmir were heavily influenced by Jamaat-e-Islami clerics back then. The 2019 ban on the outfit brought some relief as it weakened the grip of hardliners.

“There have been instances where Ahmadiyyas faced discrimination because of their identity, such as the rejection of their documents for the government Hajj quota. It stems from reactionary elements within certain institutions, particularly in Kashmir, who harass them,” said PhD scholar Rather. “In India, Ahmadis are considered Muslims. The Indian Hajj Committee operates under Indian laws and regulations.”

Over the years, several Kashmiri Muslim scholars and historians have written against the discrimination faced by Ahmadiyyas, but it has done little to effect a larger change in Kashmiri society.

At the college where Mohammed teaches, there is no Ahmadiyya mosque nearby. So he prays in mosques of other sects. No one there knows who he is but he is acutely aware of his ‘outsider’ status.

“They have fed this narrative that we are different so deeply that even as a Muslim in their mosques, I feel alien and I am not able to pray properly,” Mohammed added.

Two years ago, his brother entered a non-Ahmadiyya mosque in South Kashmir. After someone recognised him, he wasn’t just thrown out — the mosque was washed with detergent.

“Thank god they can’t kill us. Because we’re in Hindustan,” Mohammed said dryly.

At the Ahmadiyya mosque in Srinagar, the elderly cleric rises from a bench to offer namaz. Before walking away, he gazes out the window and recites a line from the famed Kashmiri poet Mahjoor, claimed to be an Ahmadi by members of the community:

“Vanya Mehjoor dastaan-e-dil zarur, Vannuk ti chumm na var Madno”— Mehjoor would have whispered the tale of his aching heart. But, fate offers no mercy, O Beloved.

Names have been changed in this story to protect the identities of Ahmadiyya community members.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

It is a standard practice to state that the majority community oppresses the minority and seek things like reservation, affirmative action for the minority community to address the age old oppression. In Kashmir the majority is Sunni and Shia Muslim. How come they are not forced to mend their ways and give concessions to the minorities? Hindus or Ahmadiyaas or Christians?

Some of the most virulent supporters of the Pakistan movement including Zafarrulah Khan were Ahmadiyas. They lent the backroom support and financial heft to the hooligans who toppled of the unionist ministry of Khizar Hayat Tiwana. This was one of the most pivotal acts that rendered united Punjab (and by extension India) impossible. It was only after there were anti-Ahmadiya riots in 1950s in Pakistan and the ban of Ahmidiyas by Bhutto in 1970s that they turned “loyal to India”. History is never kind to betrayers.