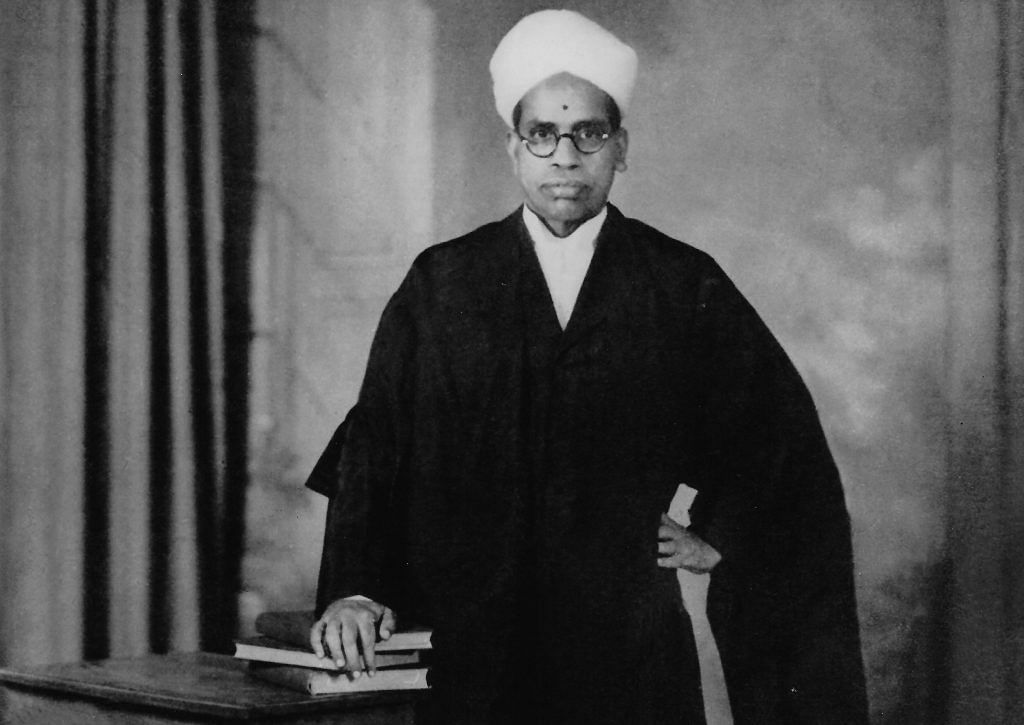

Ayyar, a member of Constituent Assembly, had an unparalleled knowledge of the world’s constitutions, said Ambedkar himself.

The architect of India’s Constitution is unequivocally remembered to be B.R. Ambedkar. In nearly every statue of him, Ambedkar grips the thick, hard-bound book he is said to have ‘fathered’.

Lesser known is that working steadfastly alongside him was Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar, a Madras (now Chennai) lawyer who, by Ambedkar’s own admission, had an unparalleled knowledge of the world’s constitutions and Indian law.

Rise to Constituent Assembly

Ayyar was born into an impoverished family on 14 May, 1883, in the village of Pudur — in pre-Independence India’s Madras but located today in Andhra Pradesh.

A small and slight man, Ayyar’s presence in the courtroom and Constituent Assembly resembled nothing of his physical stature. When he spoke, it was with eloquence and command that, according to former Sahiya Akademi vice-president K.R. Srinivasa Iyengar, “radiates its influence in the High Court buildings and sheds its reflected glory on the horizon of law”.

Also read: The man who played a role in the politics of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh

His rise as an eminent lawyer, to later become Attorney General of Madras with an 18 year-long tenure, prompted Jawaharlal Nehru to personally invite Ayyar into the Constituent Assembly in 1946 — much before Ambedkar’s induction. Not to mention the quick succession of accolades preceding his time at the Assembly: In 1926 he was awarded the Kaider-i-Hind award for philanthropy. In 1930, he was given the Dewan Bahadur title for his contributions to the country. In 1932, he was knighted.

Speaking to ThePrint, Ayyar’s grandson Krishnaswami Alladi said his grandfather was “unmatched in the power and logic of his arguments, and unrivalled in his knowledge of case law and of constitutional law”.

Drafting committee

Ayyar’s reach in the Assembly reflected these words. He was a member of nine House committees, among them the drafting committee and the sub-committee on fundamental rights. His contributions to the Constitution had to do with some the most elemental parts of India’s existence as a nation-state, namely citizenship and adult franchise.

“Citizenship carries with it rights as well as obligations,” Ayyar declared while defending the Constitution’s fifth article, which continues to define Indian citizenship today.

“We cannot on any racial or religious or other grounds make a distinction between one kind of persons and another, or one sect of persons and another sect of persons, having regard to our commitments and the formulation of our policy on various occasions.”

Ayyar was also firm about the powers a president can wield during periods of Emergency. He agreed that not all fundamental rights be withdrawn, but also said, “Freedom of speech, right of assembly and other rights have to be secured in times of peace but if only the State exists and if the security of the State is guaranteed. Otherwise, all these rights cannot exist.”

As the last days of the Constituent Assembly approached, Ambedkar paid homage to Ayyar in his concluding speech in 1949, saying: “I came into the Constituent Assembly with no greater aspiration than to safeguard the interests of the Scheduled Castes. I had not the remotest idea that I would be called upon to undertake more responsible functions. I was therefore greatly surprised when the Assembly elected me to the Drafting Committee. I was more than surprised when the Drafting Committee elected me to be its Chairman. There were in the Drafting Committee men bigger, better and more competent than myself such as my friend Sir Alladi Krishnaswami Ayyar.”

Also read: This tribal leader who opposed prohibition also led India to first Olympic hockey gold

‘Acceptance of Constitution’

For Ayyar, the true test of the Constitution’s worth lay in the hands of India’s laymen. In his first lecture after the Constituent Assembly disbanded, he was pleased to note that voters thronged throughout the country.

“The recent elections based on universal suffrage in which a majority of the adult population of India, men and women, literate and illiterate, propertied and non-propertied, have taken part with enthusiasm and unexampled orderliness — a circumstance which has elicited the admiration of foreign observers and critics — have demonstrated, if any proof was necessary, the acceptance of the Constitution by the people of India as a whole.”

Ayyar’s involvement in the Constituent Assembly was an interlude in his profession as a lawyer, which he returned to after the Assembly dissolved. Despite his considerable fame, he continually refused opportunities that would elevate him to a Judge.

He died on 3 October, 1953, in Chennai, leaving behind the home he built in 1919, Ekrama Nivas, where generations after him continued to live.