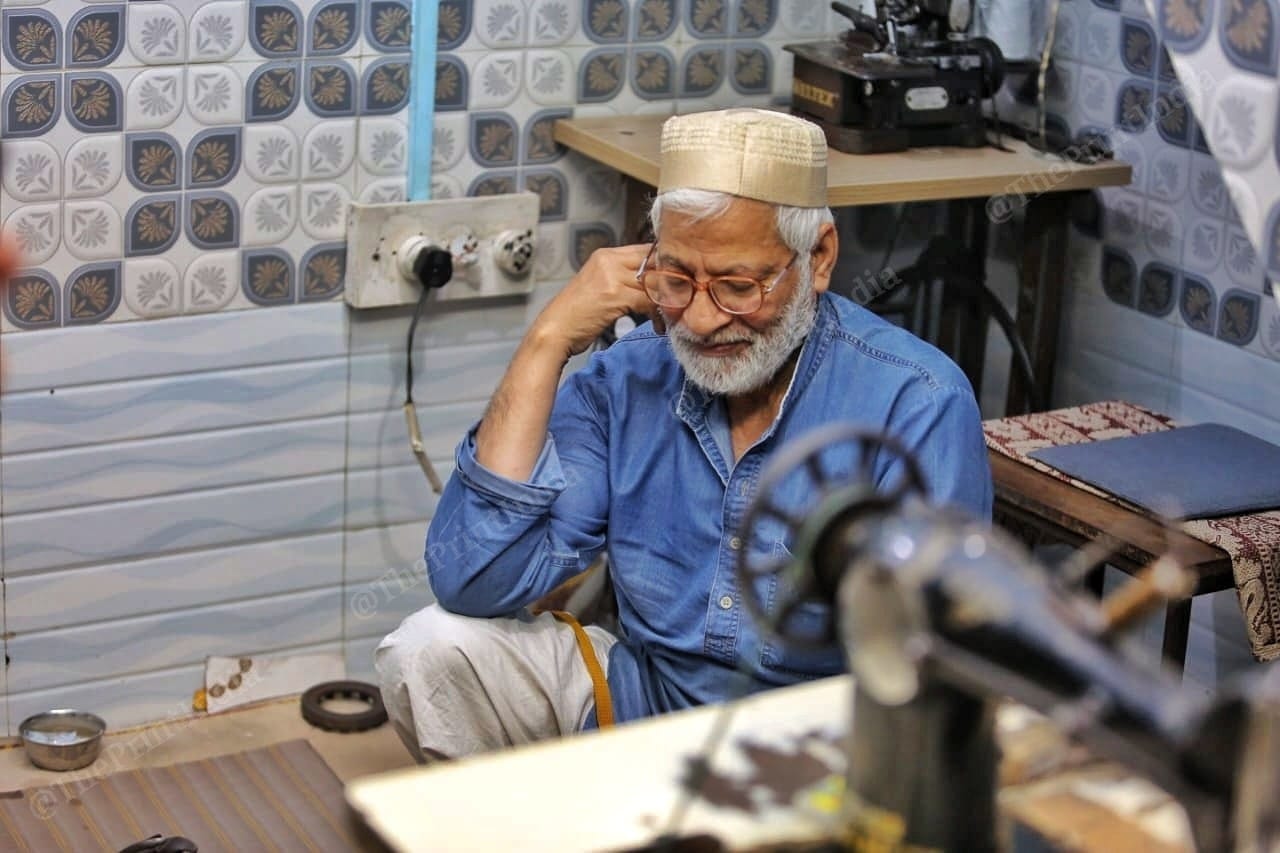

Maliana (Meerut): On the outskirts of Meerut, in one of the narrow lanes of Maliana village, a crowd has gathered outside the shop named “Ahmed Tailors.” Vakil Ahmed, 60, folds the cuff of his shirt and shows the bullet wound in his forearm. He then lifts his shirt and shows another wound in the back.

“This is the fourth time Ahmed has shown his wounds since the morning, but for what?” remarks one in the crowd.

Ahmed was the first prosecution witness in the 23 May 1987 massacre in which 68 Muslims were killed by a mob that allegedly included personnel from Uttar Pradesh Provincial Armed Constabulary (PAC).

After over 800 court hearings over three long decades, the residents of Maliana were heartbroken when the Meerut district court set free all 41 men accused in the massacre. In the judgment passed on 31 March, additional district and sessions judge Lakhvinder Singh Sood underlined the lack of “sufficient evidence…to convict the accused” as the reason.

Recounting one of the court hearings, Ahmed says that despite showing his physical injuries, the judge kept asking for proof.

“What other proof can I give? Are my bullet wounds and the injury report not enough to show what happened that day? Ahmed asks as he adjusts his shirt and unfolds his cuff.

“And now, they have set free the accused saying that there was no evidence. Who am I then?” he adds.

In the three decades, the massacre survivors have held on to a fledgling sliver of hope, court documents and the dates on the calendar. The conviction of 16 PAC personnel five years ago by the Delhi High Court in the Hashimpura massacre signalled the possibility of closure, even if belated. But the Meerut court’s ruling has refreshed their woes. Shoddy investigations and inquiry committees, political apathy and complicity had weakened their case at every stage.

Also read: What’s a life sentence when life is almost over: Hashimpura victims’ kin on court order

A common briefcase

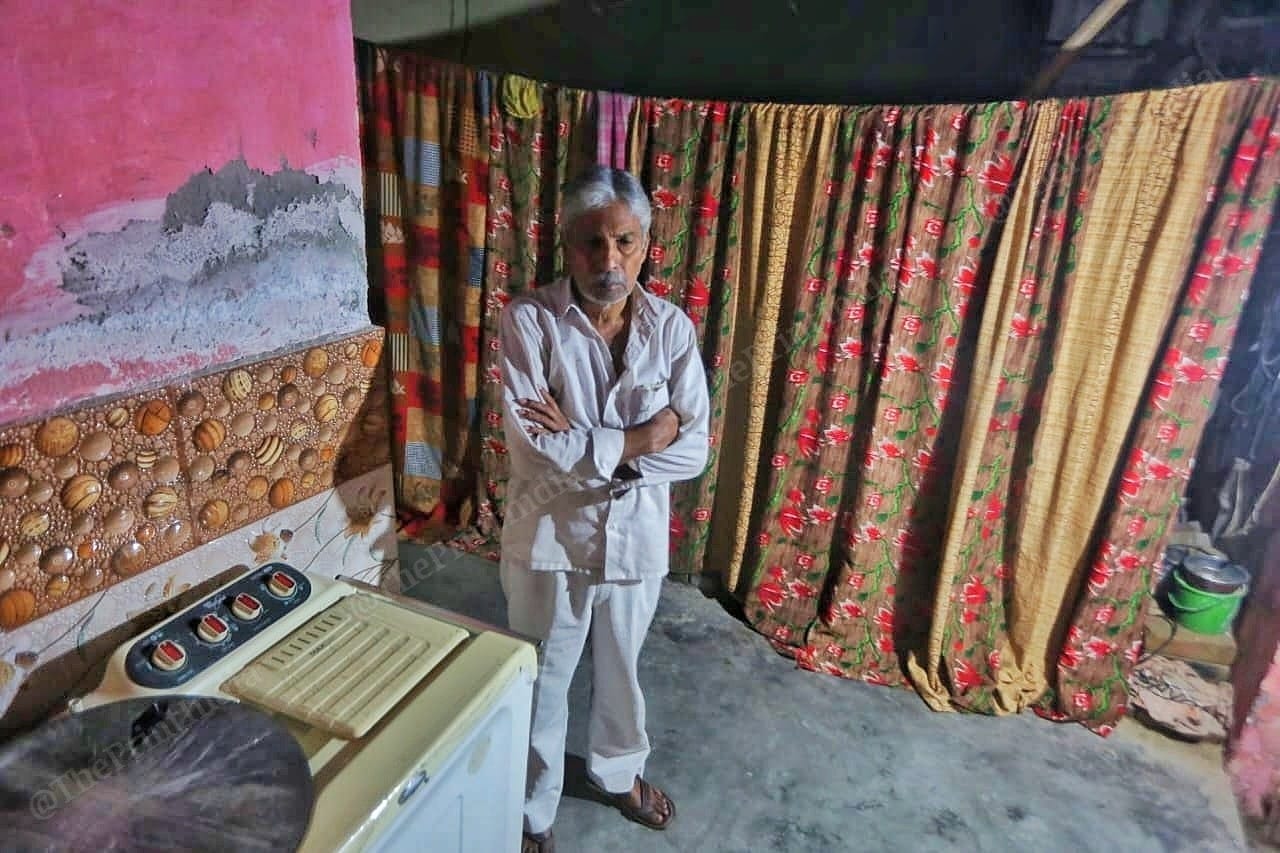

Ismail Khan, 63, was in Ghaziabad to distribute the wedding card of his younger brother Yunus when he learned about the killing of his family members. Khan’s brother was to get married three days later and the house was full of relatives and celebrations.

But then evil happened. Khan’s eleven family members including his parents, grandparents, siblings and a cousin were killed.

“An evening newspaper Dainik Hint announced the massacre and death of 11 people in a family. When I read the news, I learned that it was my family,” Khan recalls.

It took him a week to go back to his village because of the curfew; when he reached, it wasn’t the same anymore. There was an eerie silence, Khan recalls. No one greeted him but looked with dead eyes.

“My house was looted. I learnt from neighbours that my grandfather and parents were killed and thrown in the well.”

Soon after the incident, Khan shifted to Ghaziabad with his wife and two sons. He has never gone back since.

Khan opens a briefcase in which he has neatly kept the newspaper clippings and the death certificates of his family members. A briefcase with death certificates, documents and newspaper clippings is a common sight in the houses of Maliana’s victim families.

“This is all I am left with. These are the memories I keep dearly. A death certificate can sometimes be a stark reminder of a relationship,” Khan rubs his eyes.

“I wish I could see my mother one last time,” he closes the briefcase and cleans the surface with a cloth.

Khan is not the only one. Nawabuddin, who lived in the Sanjay Colony where most of the residents were Muslims and Dalits, also shifted to a nearby Muslim-majority locality. The incident had left behind a deep mistrust. It was no longer safe to live there anymore.

“We (Muslims) and Dalits used to live peacefully until that day,” Nawab says. A driver by profession, he lost his father to the bullets.

‘It feels like yesterday’

Yameen Malik was 25 when he lost both his parents to the violence. He was hiding with his sisters in a shop when a mob fired indiscriminately at the Muslim residents. When the violence waned in the evening and a curfew was imposed, Malik and his sisters made their way to their home. Malik remembers blood splattered on walls and corpses scattered in the streets like fruits from a tree that had been blown by the gusty winds.

“I asked my sisters to stay back as I went inside the house,” he says. Their house was now a pile of debris — and the charred bodies of his parents were lying there.

“That sight never leaves me. It feels like yesterday,” says Malik as his son Riyaz holds his hand tightly.

Malik claims that the bodies of his parents were taken away by the police for post-mortem but were never returned to him.

“I kept visiting the police station asking for the bodies for months but they kept giving excuses. I couldn’t even cremate them,” Malik fumbles.

He is joined by Irfan Siddiqui, who was 16 years old at the time. Irfan was playing with his friends when he heard the sound of bullets ringing in the air. They all ran to find a shelter somewhere.

“We went to the nearby house and kept crying. The windows and doors of all houses were shut and everyone was advised to stay quiet till the rioters leave. We were scared for our lives. My childhood died that day,” he says.

‘The younger generation’

Thirty-six years is a long time to remember the details but the eye witnesses of the Maliana massacre have not forgotten anything. The grieving has become a part of the folklore. Elders narrate the stories of violence and crime to the youngsters to keep the memory alive.

Riyaz, 30, son of Yameen Malik, was born six years after the bloody massacre but he knows everything word for word. When Malik fumbles, Riyaz intervenes to complete the sentence.

“Since I was a kid, my mother and father would narrate the story of a daaku (robber) who killed my grandparents and wiped the Hindu-Muslim unity from the region,” says Riyaz with a smile.

Riyaz has accompanied his father to each police station visit and court hearing. And he won’t give up.

“If we don’t get justice. I am well prepared to take the legal battle forward,” he adds.

At a kiosk in Maliana, a group of young men sit on the benches sipping tea while women are tethering goats to the trees outside their house. Meerut court’s judgment is the topic of discussion.

Abdul, 26, born ten years after the incident, points at the road where his uncle was shot dead.

“My father told me that Mamu was killed here.”

Abdul’s friend Shafi, who was born one year after the killings, tells him how his mother has not been able to sleep since the judgment.

“Last night, I gave her a sleeping pill.”

And suddenly everyone fell silent.

Also read: Hashimpura verdict exposes India’s criminal justice system

What the court judgment says

Judge Sood listed a series of ‘loopholes’ in the case before acquitting all 41 accused men.

“The accused named in the FIR filed by the police was done after getting the voter list. It has been noted that few of the accused in the case had passed away before the incident,” the judgment reads.

Among other observations, the judge noted “inconsistency” and “contradictions” in witness testimonies, highlighting that no coherent explanation was given for the “changes” in the statement given to the police and to the court.

The judge noted that the weapons, as mentioned by the witnesses, were not found in the possession of the accused.

During cross examination, as per the judgment, one of the prosecution witnesses told the court that he wrote the names of the accused from the voter list “under pressure” by the officers at the Transport Nagar police station and that he “does not know the accused.”

The judge also said there was no evidence regarding the “specific role of any accused.”

‘Dead are just statistics’

Inside his chamber in Meerut district court, Alauddin Siddiqui, the lawyer representing the victim families, is writing an appeal to be submitted at the Allahabad High Court. Visibly grim, Siddiqui is not greeting people and is engrossed in skimming through the files.

“I was shocked after hearing the judgment,” he says.

In 1987, the Uttar Pradesh government announced a judicial inquiry under the Commission of Enquiries Act 1952. The committee was headed by Justice GL Srivastava, a retired judge of the Allahabad High Court.

“The commission’s reports died a silent death because the documents were never presented before the legislature. No one knows what was in the report,” says Siddiqui.

In 2008, twenty years after the violence, the police framed the charges. The only FIR filed in the case, by Yaqub Ali who was beaten up by the police, was misplaced, Siddiqui claims, hindering the case for years.

“In the court, the defendant would always bring up how there was no FIR, so the case can’t follow. When asked about it, the police would say they have misplaced it. What can one do?” he asks.

Yaqub, a direct victim of the slow court battle in the last three decades, has resolved to fight back.

“I will file an appeal in the high court. If the high court disappoints us, I will go to the Supreme Court. Until I am alive, I will not leave the case,” Yaqub asserts.

Siddiqui calls the entire case a “travesty of justice” right from the moment the first FIR was filed.

“I lost my prime pursuing the case. Look at my grey hair. For them, the dead might be mere numbers but they were lives I gave my entire life to defend. I will fight back,” he says, and then breaks down to cry profusely as a fellow lawyer consoles him.

(Edited by Prashant)