New Delhi: Artist Rameshwar Broota came of age alongside the Triveni Kala Sangam—they grew in tandem. He became one of India’s best known modernists, and Triveni became a hub— the nucleus of cultural education, art heritage and a distinct mood. One which flowed easily; seamlessly moving from painting to theatre to various classical dance forms—all congregated in an unbreakable middle.

It’s been 75 years since. The city has changed, but in many ways, Triveni hasn’t. But it is a landmark moment in its history to pause, reflect, and more importantly, memorialise. And in order to memorialise the institution that has created an unwavering community, founder Sundari K Shridharani’s son Amar and the Triveni team are building an archive that is going to be exhibited next year. There are architect Joseph Allen Stein’s early maps, which are currently undergoing restoration—blueprints of what was to come. Divided by category, there are sections on each classical art form performed at Triveni. There are old tickets of Manipuri ballets and documentation of early shows.

For example, in 1994, Shridharani wrote to a journalist at The Hindustan Times, requesting the paper’s dance critic to cover Nritya Rupam, a show choreographed by Bharatanatyam dancer Jayalakshmi Eshwar. Up until then, they had been mostly performing Manipuri ballets.

“Since Triveni imparts training in other styles of dance as well, which are conducted by eminent gurus, we have decided to periodically present their creative works also,” she wrote. It was the beginning of a new dawn.

Much of the repository stems from letters, reviews and newspaper articles which are being used to stitch the archive together. These vignettes are then going to be substantiated by audio-visual presentations, interviews with those who have had long associations with the cultural centre, as well as videos of past performances. So far, theatre director Feisal Alkazi, Broota and Odissi dancer Pratibha Jena Singh, who is the daughter of renowned Odissi dancer Surendra Nath Jena, have shared their oral histories.

In typical Triveni fashion, the archive will be open access. The exhibition will be on display at one of the centre’s four art galleries from February next year. A no-holds–barred collection of memories and art in all its forms, the archive is an ode to the culture that has been created and to its one-woman powerhouse, Sundari K Shridharani.

“A lot of it [the archive] is based on old connections, to go down memory lane. There are teachers and students who’ve been writing to us,” said Amar Shridharani. “We’re issuing open calls through our newsletter and Instagram.”

Dibakar Banerjee’s Khosla ka Ghosla was filmed at the Triveni Kala Sangam. In a scene critical to the plot, where one character tells another that she is leaving New Delhi for New York, they are sitting around a table at the canteen. In 1976, parts of HK Verma’s Kadambai, which stars Shabana Azmi, were also filmed at locations across the centre—the amphitheatre and the glass door at the entrance. For those who’ve spent time—taking classes or chatting at the cafe—it’s easy to stumble upon a snapshot of the Sangam. At one point, it was a truism: cultural policies were ironed out over cups of tea at the cafe. Shyamsundar, the security guard, has manned the halls for three decades. There’s a potent mix of memory, history, and culture at every step.

A mixture of materials, the archive stems from many sources. Students and teachers who’ve been there for decades, as well as those who’ve had fleeting interactions—perhaps they’ve watched the occasional play or sipped cups of tea at the Triveni Terrace Cafe. Disparate forms—photographs, newspaper articles, posters, brochures and tickets, and interviews—will be placed in unison to shape the archive.

Despite being located in the thick of Mandi House, where all of Delhi’s historic and epoch-shaping cultural institutions continue to exist, Triveni Kala Sangam occupies a special place in the cityscape. It focuses equally on teaching, nurturing the next generation of artists while providing a space for cultural confluence. This governing ethos is palpable—part of a sensory experience available to all those who enter the building on Tan Sen Marg.

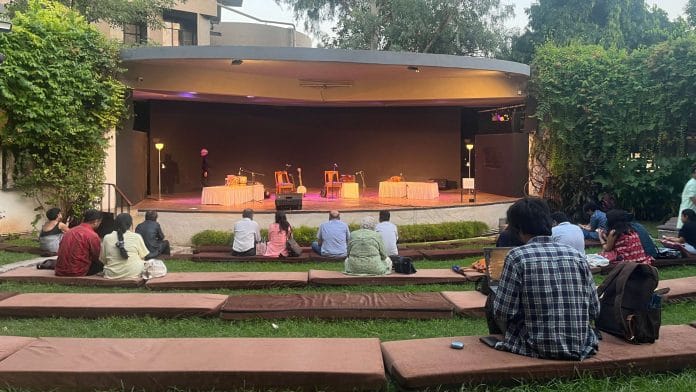

The thunk of a payal slips into the gallery and conversations at the cafe. The amphitheatre is being set up, instruments falling into line one after another on stage. This dynamism of sound and mixture of rhythms has long shaped life at Triveni.

“It’s always been very inspiring. You saw the best of artists and dancers,” said artist and Bharatanatyam dancer Shruti Gupta Chandra, who joined art classes at Triveni Kala Sangam on the insistence of her grandmother in 1972, at the age of 11. “When you walked in, on the right, you heard Manpuri dancers and the beats of their drums. The canteen was buzzing. The art gallery was right there,” Chandra added.

She recalled the kind of accidental access Triveni Kala Sangam provided at the time, like MF Husain walking into a show and witnessing “the best dances and artists.”

Broota also mentioned being surrounded by the best in the business when he was finding his footing as a young artist. He’d meet sculptor Dhanraj Bhagat and modernist painter and printmaker Kanwal Krishna regularly.

It all started with two rooms

Hoardings at the front lawns advertise a diversity of events and exhibitions currently taking place. At Gallerie Nvya, artist Krishen Khanna’s hundred–year centenary is being celebrated. The amphitheatre is preparing to witness a performance by Chaar Yaar. This mingling of forms is what was envisaged by Sundari K. Shridharini, who started Triveni Kala Sangam in two rooms of Connaught Place.

In a room on the first floor, there are boxes filled with documents and photographs that are spilling out of their folders. This included an old ticket for Manipuri Dance Ballet from 1994, a mere slip of paper, as well as a newspaper clipping with a black-and-white photograph of a young Sundari Shridharani, standing outside the amphitheatre, flipping the pages of a book. Tangible evidence of Triveni’s history has also, in large part, been preserved by Shridharini. She passed away in 2022 at the age of 92 and was meticulous in filing away any clipping that had even the slightest mention of Triveni Kala Sangam.

This practice extended far and wide. If she saw any of ‘guru-jis’ mentioned in the newspaper, she’d promptly cut out the article, keeping one copy with herself and sending another to them.

By the end of her stint in Connaught Place, Shridharani had students and teachers spilling out of their two rooms. She needed more space and eventually found her way to Mandi House. Initially, government land had been allotted to her and her students. It was also her place of residence. After requesting architect Habib Rahman, it was Joseph Allen Stein who ultimately secured the job. It was inaugurated by Sarvapali Ramakrishnan in 1963. Shridharani wanted a physical rendering of her imagination, the kind of space she envisaged.

The building’s open-air exteriors and boundaries flow into each other, mirroring the essence of what’s inside.

Many of Mandi House’s cultural institutes came up within the same decade. Rabindra Bhavan, which houses the three akademis, was Nehru’s vision, an act of nation-building. Meanwhile, Shridharani’s was entirely her own—born out of one woman’s moxy who, at the time, was unable to fund her imagination.

“When Mrs Shridharini approached the architect, Mr Joseph Allen Stein, for assistance in designing a home for the Sangam, she mentioned the small amount that she could find but said she wished to have a fine building,” reads a newspaper article, a profile of female art directors from the late 70s. “The architect expressed his amusement because the specifications she indicated needed many times the sum she had.”

However, as the story goes, she was persistent to the point that Stein agreed to design the building in accordance with her specifications. This became yet another testament to Shridharani’s single–mindedness and the fervour needed for institution-building. Literally.

“The recognition which the Sangam has achieved, the high standards which the courses provided at the institution maintain and the popularity of the Manipuri dance troupe are a tribute to the abilities of a woman in developing and running at the Triveni Kala Sangam,” read the article, which profiles women from around the world.

For Amar Shridharani, the archive is a way to take his mother’s legacy forward, to memorialise what she created against all odds.

“She had an eye, you know, to see and attract the best. Even though some [of her teachers] were very young. She somehow sensed a promise in terms of quality,” said Rachit Jain, an artist working on the archive. “For example, Mr Broota was very young when he joined.”

While he was a student at the Delhi College of Arts, Broota chanced upon Triveni Kala Sangam as an adda, a place where he could chat with fellow artists. But almost immediately, he was hooked. At the time, his aspirations were limited. He envisioned a future as a school art teacher. But soon enough, he received a call, and Triveni became the fulcrum of his life as both teacher and practitioner.

“The whole environment was very artistic. The music institutions, the theatre, and the school of drama. Everything was connected with art,” he said. “I’d listen to classical music in the evening, and spend the night watching theatre. It was such a beautiful experience. Receiving a call to join was a godsend.”

Broota has been attached to the Vadehra Art Gallery for decades now. But his exhibitions still open at Triveni, where he secured a teaching position which he has now held for close to 50 years.

The corridor outside Broota’s room is lined with canvases. One is covered with overlapping figures in colours of black, white and brown. Crossing the pottery room is a necessity, where women are chatting while deftly manoeuvring bits of clay.

His room at the centre is stacked with canvases of various sizes, which look to be in varying degrees of completion.

Also read: The shifting phases of Delhi’s Mandi House—Institution, Memory, Resistance

Architecture and the importance of the space

There’s a black and white photograph of Shridharini on site with the acclaimed Joseph Stein, but it’s almost as if she’s the real major domo of the operation. The building contains many of his signatures—an abundance of jaali-work and pale, unobtrusive stone. Stein’s signatures are peppered across Central Delhi, including the IIC and the India Habitat Centre. Lodi Estate was once popular as ‘Steinabad’.

Engagement with art, no matter how serendipitous it may seem to a viewer, is also an architectural element. To reach the cafe, one must cross three art galleries and encounter the amphitheatre. The archive will attest this too, as it contains several of Stein’s early drawings.

“My only agenda is that whatever mom did shouldn’t go down. We’re the last generation that knows the beginning of Triveni,” Amar said, adding that his mother studied under dancer Uday Shankar at his centre in Almora, where she met a “cross-section of people.” Her life grew rich and filled with luminaries like Zohra Sehgal, Pandit Ravishankar and Guru Dutt. Influenced by the greats, she was itching to create an institution of her own.

“But there were no shortcuts. Art isn’t necessarily a priority for a newly independent country,” he said.

At Triveni, the past converges with the present. Zuleikha Chaudhuri, theatre maker and director of the ‘Alkazi Theatre Archives’, continues to present the archival exhibitions at Art Heritage, which is located in the basement of the main building. While Art Heritage is the Alkazi Foundation’s sister organisation, it’s the space itself that propels her forward in this day and age of swanky gallery spaces.

“The point of an exhibition is that it’s publicly accessible. At Triveni, you’re getting a public that you wouldn’t necessarily get otherwise,” she said, referring to the centre as a “porous space.” “It’s not just an art audience, you’re getting a range of people who are interested in different things. Theatre archives can’t be locked in a building that’s difficult to access,” Chaudhuri said.

The sheer weight of Triveni lies in its chameleon-like ability to mould itself to all kinds of art forms and conversations. It’s in the lack of posturing, the absence of feigned gravitas attached to today’s institutions.

“There’s no rigidity here. It’s a different world,” said Broota.

(Edited by Saptak Datta)