On a warm June evening in Potsdam, an iconic European ballet met one of India’s most ancient classical dance forms — and something quietly remarkable happened.

Odissi dancers moved to 19th-century Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s strings. Baroque hand gestures folded into temple mudras. Indian percussion thrummed under a darkening summer sky.

The production, Indian Swan Lake, closed this year’s Musikfestspiele Potsdam Sanssouci — one of Europe’s leading classical music festivals, held at the UNESCO-listed Sanssouci Palace. Supported by the Embassy of India in Berlin, the Tagore Centre, Indian Council for Cultural Relations, and German partners, the performance wasn’t a typical cultural showcase. It was something riskier, deeper — a shared act of imagination.

Here, Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake met Odissi, the refined classical dance of Odisha, with a new narrative drawn from Nala and Damyanti, the ancient Indian epic of exile, devotion and reunion from the Mahabharata. The parallels between these two tales— a love tested by fate, jealousy, and demonic trickery – were subtle but striking. Like Odette, Damayanti is a figure of grace trapped by forces beyond her control. Like Siegfried, Nala must choose between illusion and truth.

That this mythological Indian story unfolded in the gardens of a Prussian palace, before an audience of nearly 2,000 Europeans, felt quietly radical. It wasn’t a tribute to Indian classical forms. It was a reclamation — a moment in which Indian storytelling took its place, confidently and equally, within the canon of European high culture.

Tchaikovsky meets Indian ragas

Onstage, Indian and European dancers performed side by side. A live chamber orchestra wove Tchaikovsky’s melodies into Indian ragas and rhythmic cycles. The result wasn’t fusion, it was conversation. One born from vulnerability, trust and genuine creative partnership.

India’s Ambassador to Germany, Ajit Gupte, said in his opening remarks that the performance was a shared act of creation — one that connects not by erasing difference, but by revealing common ground through expression.

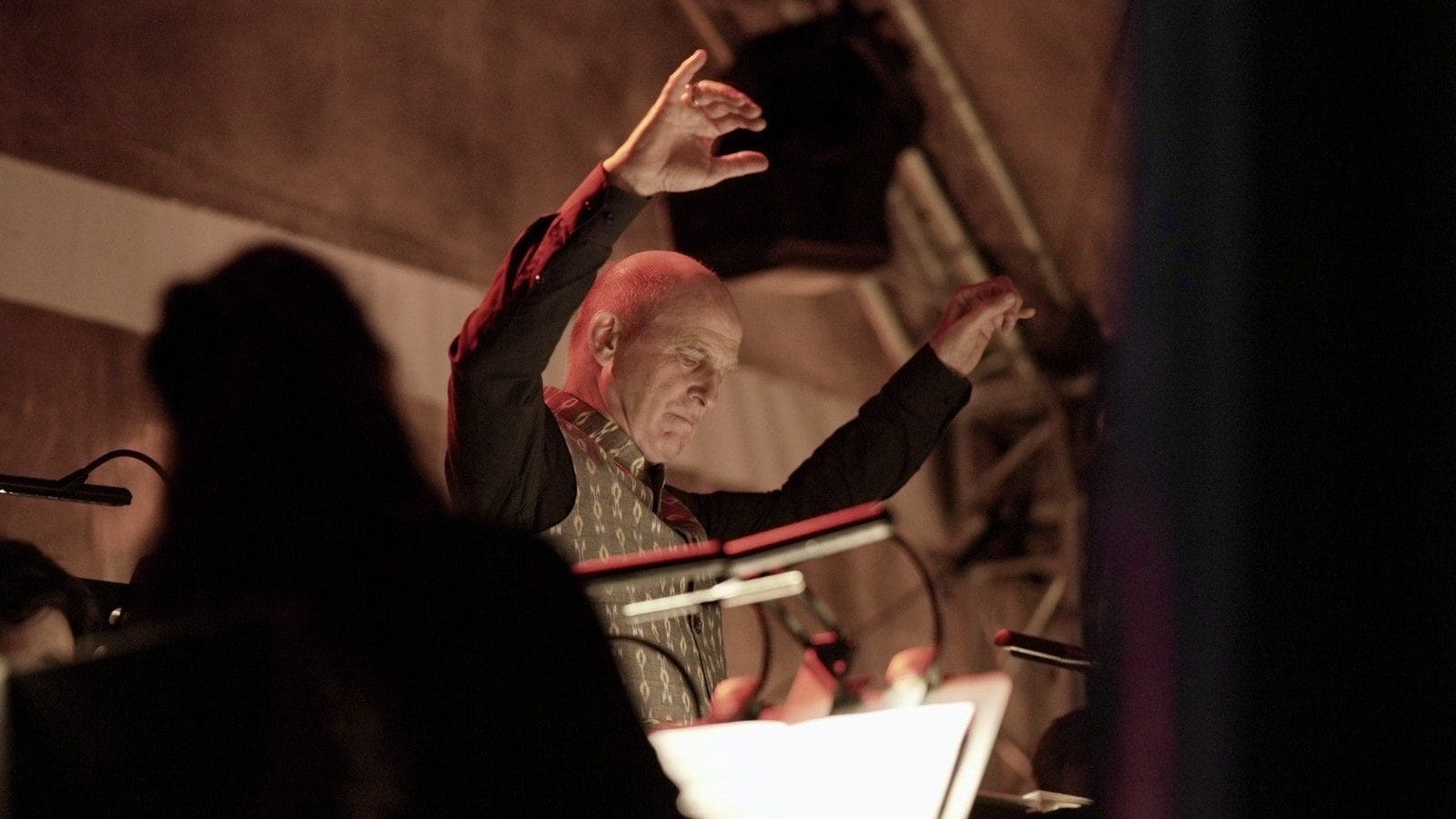

The idea for Indian Swan Lake began with an invitation — from German conductor Werner Ehrhardt, artistic director of the Orchestra l’arte del mondo, who had been imagining a project like this for nearly two decades.

India is often positioned in Europe as a jewel, and I’ve grown used to receiving proposals that celebrate Indian art as something rich, colourful, and exquisite but slightly apart. This felt different. Over weeks of conversation, it became clear that Ehrhardt and the Musikfestspiele team weren’t asking India to perform as a guest country. They were inviting us in as co-creators.

We accepted. None of us, I think, fully anticipated how difficult — and how transformative — that would be.

The production was choreographed by two extraordinary women: Italian baroque choreographer Deda Cristina Colonna and the Padmashree award-winning Odissi exponent Aruna Mohanty, who brought with her a team of dancers from the Orissa Dance Academy. Their task wasn’t to translate between styles, but to seek a shared emotional logic. “Tradition is not fixed,” Aruna told me during rehearsals. “Even sacred stories have always been reinterpreted, paraphrased, retold.”

That openness shaped everything — including the music. Indian and Italian composers developed the original score together. Rehearsals stretched from Bhubaneswar to Berlin, often complicated by time zones and translation — not just of language, but of aesthetic and rhythm. In the West, rhythm tends to be linear. In India, it’s cyclical. Even the concept of tempo had to be negotiated. As Ehrhardt put it, they were inventing a shared language from scratch.

And in the end, it worked.

Also read:

Swan Lake in a new accent

Over three performances in Germany — in Aschaffenburg, Leverkusen, and finally Potsdam — Indian Swan Lake played to packed houses and standing ovations. At the final show, the audience needed no programme notes to understand what was unfolding. They heard Swan Lake in a new accent — and leaned in to listen.

For us at the Tagore Centre and the Embassy of India, this was never just about visibility. It was about shifting the paradigm of how India presents its culture abroad. Too often, classical Indian arts are framed as heritage — precious, beautiful, and firmly in the past. Indian Swan Lake proved otherwise: these are living languages, capable of innovation, dialogue, and global resonance.

In the world of cultural diplomacy, we often speak of “soft power.” But this went further. It required creative risk, institutional trust, and a willingness to let go of control. It asked everyone involved — artists, funders, institutions — to show up not as hosts or guests, but as true partners.

That, I think, was the real achievement of Indian Swan Lake. Not only what was seen on stage, but how it was made — through months of rehearsal, negotiation, generosity, and persistence. And through the willingness of funders and institutions – from the Indian Council of Cultural Relations and the Ministry of Culture and Science North Rhine Westphalia to Bayer Kultur and the Musikfestspiele Potsdam Sanssouci – to bet on something untested.

The production is expected to tour across Europe and India over the next five years. But its real impact may be broader. It points toward a new model for cultural diplomacy – one that moves us beyond exchange and into true collaboration.

Because when Odette meets Damayanti — and a swan takes flight to the sound of a pakhawaj — it isn’t a spectacle. It’s a signal. That in a fractured world, we can still come together – not in spite of difference, but because of it.

Trisha Sakhlecha is an internationally bestselling author and diplomat, currently posted as Director, The Tagore Centre at the Embassy of India, Berlin. Her latest psychological thriller, The Inheritance, is published by Penguin Random House. Her X handle is @TrishaSakhlecha.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)