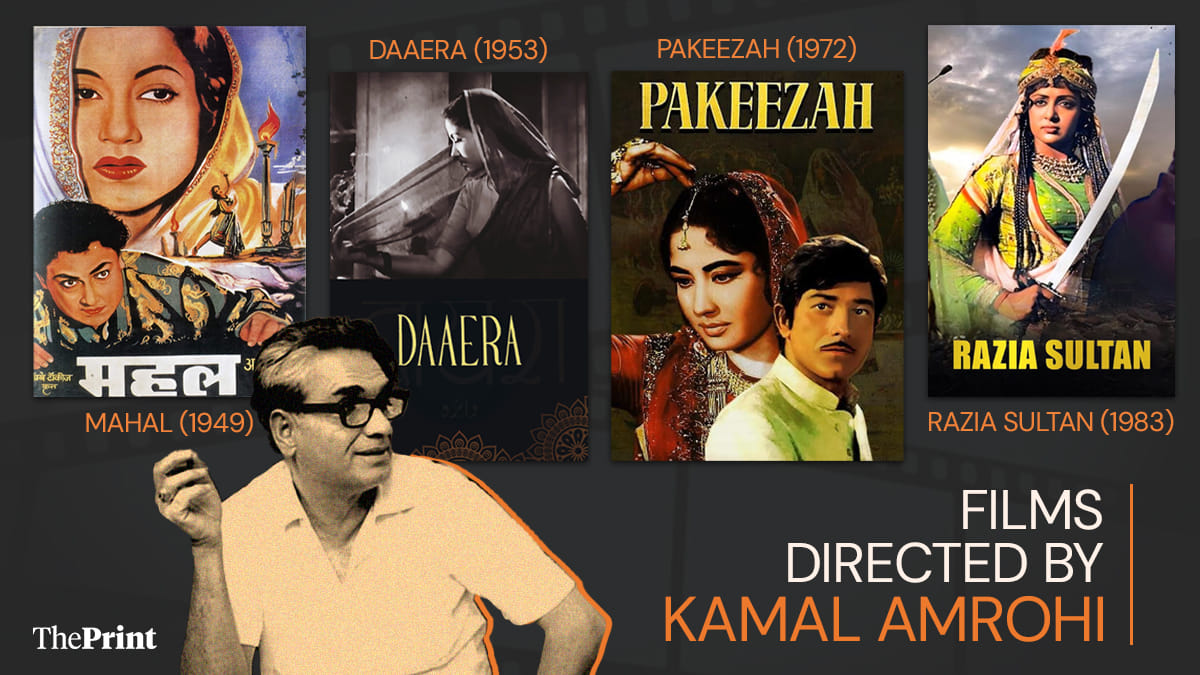

Kamal Amrohi’s 1983 period drama Razia Sultan was one of the most expensive films ever made in Bollywood. However, when it was released, it plunged the industry into crisis. The movie starred Hema Malini as Razia Sultan and featured Dharmendra in the role of her Abyssinian slave Yakut Jamaluddin. It was a box office dud and earned only Rs 2 crore against its budget of Rs 10 crore.

The success of Amrohi’s opulent 1972 film Pakeezah meant that there were high expectations from Razia Sultan. From production and set design to music, the film was as close to his vision of grandeur as possible. Distributors were banking heavily on its success, and so were the producers. But Razia Sultan brought financial ruin to nearly everyone, severely disrupting the industry’s producer-distributor network.

Amrohi’s grand filmography laid the groundwork for Sanjay Leela Bhansali productions such as Bajirao Mastani (2015), Padmaavat (2017), and Heeramandi (2024). Like Pakeezah, his Razia Sultan had all the right ingredients–superstar Hema Malini as leading lady, Bhanu Athaiya as costume designer, and Khayyam as music director. But none of it could translate into magic on screen.

Like K Asif’s Mughal-E-Azam (1960), Amrohi’s film, too, prioritised the love story between Razia and her husband over historical accuracy.

Razia Sultan, who ruled Delhi between 1236 and 1240 AD, was married to Malik Ikhtiyar-ud-din Altunia, the governor of Bathinda. But in Amrohi’s film, Sultan marries her slave Yakut, with the full support of her court, people, and religious leaders. This causes Altunia, shown as her jealous rejected cousin in the film, to start a civil war. The movie ends with Sultan and Yakut fleeing together on horseback after killing Altunia.

Heavy Urdu, no expressions

One of the biggest disappointments in Razia Sultan was the lack of on-screen chemistry between Hema Malini and Dharmendra. The two Bollywood heavyweights had tied the knot just a few years before the film’s release--though the spark of their relationship couldn’t reflect on the silver screen.

The use of dense Urdu made it difficult for people to understand dialogues and connect with the film. It was almost as if the actors were reading from a script instead of experiencing or representing the emotions behind the words.

Hema Malini’s expressions are mostly wooden. It is only in the song Khwab Ban Kar Koi Aayega, which features Parveen Babi as Razia’s aide Khakun, that her emotions are the most visible. Even as she bids farewell to her father for the war, Malini’s eyes remain expressionless. Dharmendra, who was blackfaced for the sake of representing his character’s ethnicity, also struggles to emote in most scenes.

Also read: Karz, 1980 cult classic gave us Simi Garewal as Lady Macbeth and youth anthem Om Shanti Om

Captivating music

Razia Sultan’s only standout feature was its album. From Kaifi Azmi to Jan Nisar Akhtar, it had some legendary lyricists behind it. Khayyam even received a Filmfare nomination in the ‘Best Music Director’ category.

Akhtar’s lyrics infused life into Khwab Ban Kar Koi Aayega and Aye Dil-E-Nadaan, sung by Lata Mangeshkar. In one scene in Khwab Ban Kar Koi Aayega, Khakun leans over Razia and caresses her, her white plume covering Razia’s face, serving as a visual metaphor for physical closeness.

What prompts the viewer to guess it is a kiss is how a woman reacts to the moment. Her wide-eyed expression is noticed by another, who with a slight nod tells her colleague to let them be.

Decades later, another song perfected a similar setting. Binte Dil from Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Padmaavat (2017) showed intense chemistry between Ranveer Singh, who played Alauddin Khilji, and Jim Sarbh, who played his slave Malik Kafur. The sexual tension between the Emperor and his slave has moments of intense eye contact and a touch or two before Khilji walks away, refusing to give in to the obvious desire for Kafur. In both movies, the slaves express a desire for their masters while demonstrating unwavering loyalty.

Razia Sultan could have been an exploration of the struggles and challenges of Delhi Sultanate’s only female ruler. But it turned out to be an insipid narrative instead.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)