New Delhi: A terabyte and a half of fragile history changed hands in Delhi this week, as Professor Shanker Thapa handed the India International Centre the digitised version of 1,285 Sanskrit and Buddhist manuscripts, gathered from 67 private collections in Nepal.

Since 2010, Thapa, the former dean of Lumbini Buddhist University, has been digitising manuscripts for the British Library’s Endangered Archives Programme. He shared his trove in Delhi at the request of IIC’s international research division, which is building a digital inventory of Sanskrit and other language manuscripts.

It is a hard-won collection. Thapa spent years persuading families in Nepal to share their bounty of manuscripts, often tucked away in shrine rooms.

“I focus on private collections, and it was next to impossible to convince those people to open their manuscript chests,” said Thapa at IIC, where he delivered an hour-long lecture on how these texts are linked to Indian Buddhist traditions and their role in preserving ancient wisdom.

Titled ‘Buddhist Sanskrit Manuscripts of Nepal: Continuity of Ancient Indian Textual Traditions in the Himalayas’, the 13 September talk had former ambassador and IIC president Shyam Saran and manuscript expert Sudha Gopalakrishnan seated with Thapa. Among the audience were Congress leader Jairam Ramesh and other history enthusiasts.

“These are the legacy and heritage of the entire subcontinent and part of the shared cultural space,” said Saran, adding that manuscripts, once considered esoteric, are now subjects of great interest.

The IIC’s endeavour comes at a time when the Modi government is moving forward with its Gyan Bharatam Mission to digitise one crore manuscripts across India.

Scholars like Thapa, Saran added, have shown governments and institutions their shared responsibility to sustain and nurture manuscript heritage. With 40 years of teaching experience, including in South Korea and Japan, Thapa has written 18 books and over 100 research articles on Buddhism.

“His work is remarkable for its range and its output,” said Saran, noting that Nepal is probably one of the richest repositories of such manuscripts.

Also Read: Scholars call for digitisation of Indus script symbols. It’ll make decoding easier

Manuscripts as a bridge

Until the 12th century, scholars from across the subcontinent travelled to Nepal to study Buddhism. Nepalese monks trained at Nalanda and Vikramshila produced many manuscripts. But over time, ritualistic aspects of Buddhism gained precedence over scholarship.

“Hundreds of scholars of eminence were in Nepal, but that tradition was gradually degraded,” said Thapa. But even as many manuscripts vanished into private collections, they remained valuable records of Indian textual traditions in the Himalayas.

“Nepal has played a role of immense significance in the development of Buddhist Sanskrit literature and preserved the tradition that went to Nepal from India,” he said. Thapa, however, noted that independent texts on Buddhism were also produced in Nepal.

Nepal’s ancient manuscripts span a wide range of subjects — Buddhist, literary, Ayurvedic, Hindu, tantra, sutra and shastra — and many are now held in countries such as India, Denmark, and France.

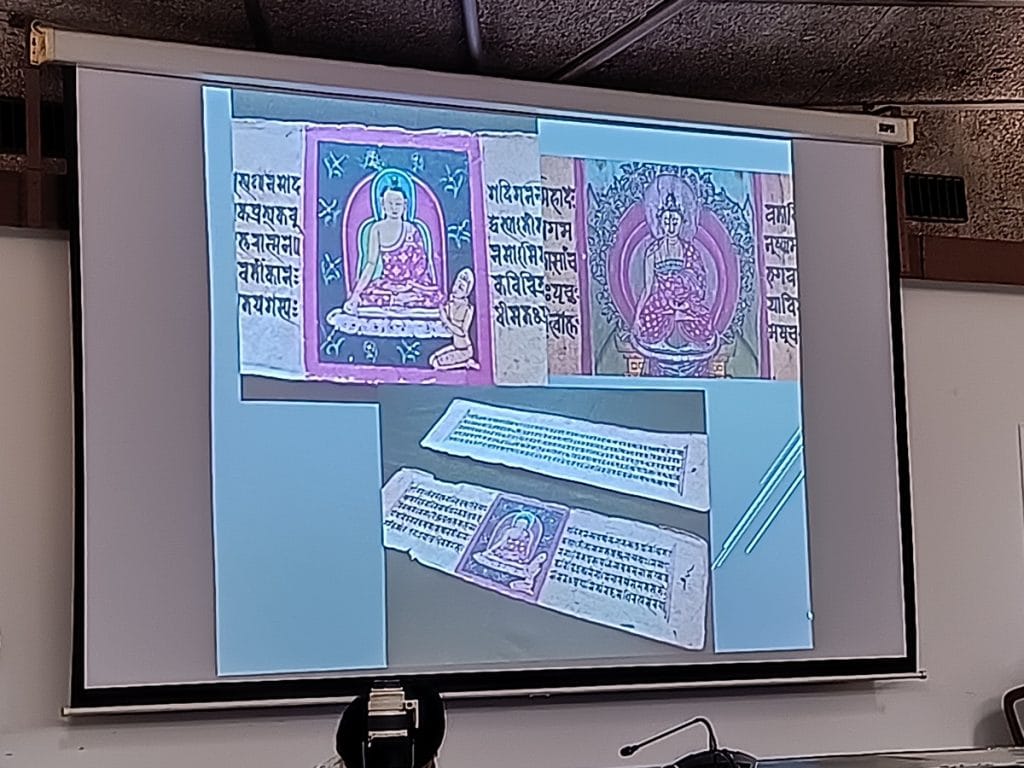

During his lecture, Thapa showed some slides of manuscripts and described their design.

“Nepalese manuscripts are decorated with miniature images, and this tradition came from the Pala dynasty. So Nepali scribes copied that tradition,” he said. “Nepal’s history of manuscripts cannot be separated from Buddhist literature in India.”

Also Read: Gyan Bharatam portal will digitise thousands of years of knowledge, curb piracy: PM Modi

Paper deities

For many in Nepal, manuscripts are imbued with spiritual meaning. Thapa said Newar families regard them as living beings.

“Newari people believe manuscripts are the emanation of Buddhist deities,” he added.

Even as the reading and writing of these texts dwindled, they continued to be objects of reverence. Thapa explained that Nepalese scribes made copies of Indian texts, transcribing them into local scripts. But even as families assembled their own collections, they rarely engaged with manuscripts as sources of knowledge.

“Manuscripts no longer remain the object of wisdom and study,” he said. “People put the manuscripts in the shrine rooms and started worshipping.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)