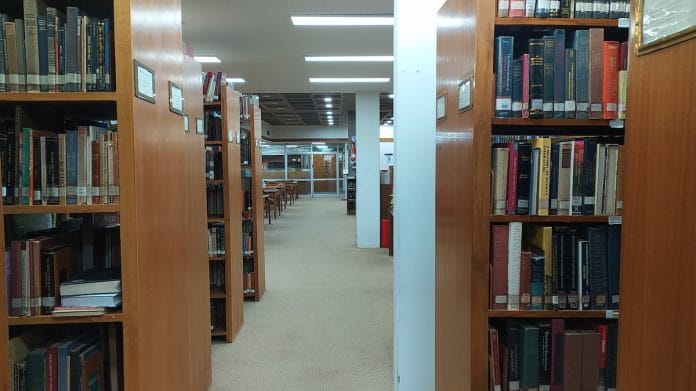

New Delhi: Whether it’s the beige carpeted floors, hushed silence piercing the air or the sight of elderly readers engrossed in their books, it’s clear that the library in India International Centre or IIC — a premier cultural institution founded in 1962 and located in Delhi’s Lodhi estate — is a space of eminence. On any given day, some of Delhi’s retired who’s who from the Lutyens’ power elite can be spotted in this library.

Lined with rows of wooden bookshelves and glass windows, the IIC library is home to over 54,565 books, ranging from topics like philosophy and psychology to religion, art and culture, with some dating as far back as the 17th century. It is frequented by the likes of Avtar Singh Bhasin, a Ministry of External Affairs retiree-turned-academic who has written prolifically on India’s relations with its neighbours like Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Tibet and China, as well as political figures like Rajya Sabha MP Jairam Ramesh.

Only members of the IIC, currently 7,000 in number, have access to the library, though temporary membership is available to non-members.

But the IIC has been viewed as an exclusive club for India’s elites. Some media reports went as far as to say that an IIC membership is “perceived to reflect on an individual’s resume as a sure-shot stamp on having arrived in career…[and belonging] to the upper echelons of the society.”

So, on 9 December, the IIC library launched a digital portal, called ‘DigiLib’, through which it made some rare books and materials available to the public online. Non-members can gain access to these materials by registering on the platform, and downloading the works for Rs 2.

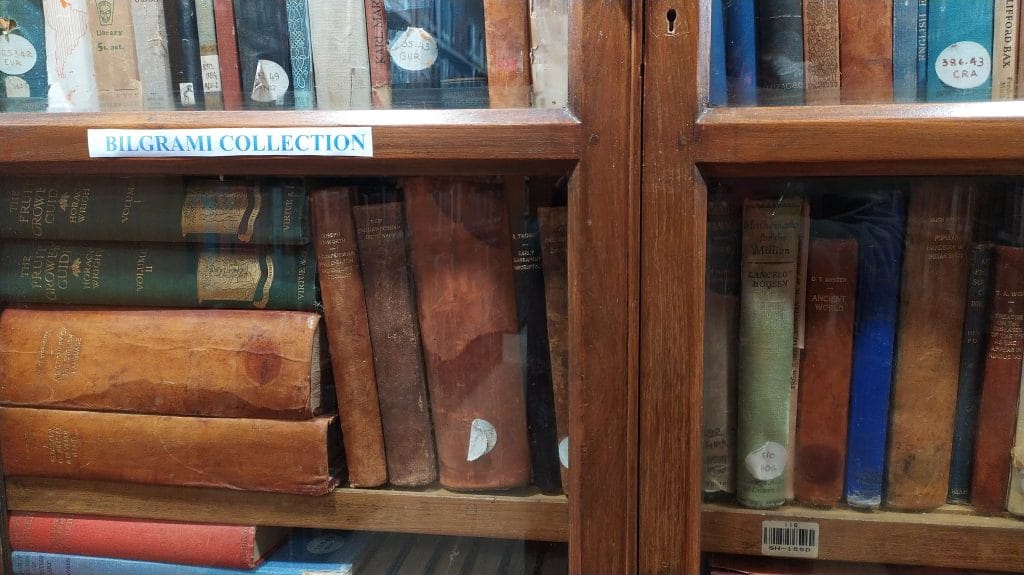

The IIC DigiLib includes works such as hand-drawn sketches by Walter Sykes George, the Anglo-Indian architect involved in designing the capital of New Delhi; a map of India’s post office network from 1835; letters penned by the RBI’s first governor CD Deshmukh; a 1959 report of the Congress Planning Sub-committee, and more. Some of the rare materials include translations from original Persian works on Mughal history and a collection of books donated by Syed Hussain Bilgrami, an early leader of the All India Muslim League.

Also read: Are you an IIC member? Don’t eat paan, walk on the lawn, tip staff, wear shorts or slippers

Preserving knowledge

According to Bhasin, who has been a regular at the IIC library for over two decades, as well as at other spaces like the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, the IIC’s collection is top-notch.

“This has always been a space I come to for the rarest of rare books. Now, they have made some of the top collections open to the public online, which is even better,” he told ThePrint.

The IIC library digitised the metadata for a total of 9,434 items and the task was completed over the course of a year, even through the pandemic.

“We wanted to preserve the knowledge of our country’s heritage and culture for current use as well as for posterity, especially legacy resources which are rare,” Usha Munshi, chief librarian, said.

Munshi and her team of nine used open-source software and certain metadata agents to create the digital repository. These agents are responsible for taking the information from the scanner and creating rich metadata, such as the author, file size, the date the document was created and keywords.

“Scanning 20 lakh pages is not easy, so we outsourced that part of the process. This was done strictly on the IIC campus,” added Munshi, who coordinated the project.

Since its launch, the digital repository has received over 7,500 online visits.

Also read: With Nagari Pracharini Sabha’s ruin, Hindi is losing a major centre and its best think-tank

‘Disseminating knowledge for rest of India’

India is home to a few digital libraries, and many more are coming up. The National Portal and Digital Repository for Museums of India, launched by the Ministry of Culture in October 2014, for example, has made the works of 10 national museums accessible online from one single portal. Meanwhile, the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts has digitised its rare archival collections in a portal called Kalāsampadā.

But what makes the IIC’s digital repository unique?

“First, it’s a very rare collection and some of these documents are old. Therefore, viewers would appreciate the condition of how they have been preserved. Also, these collections were restricted for a very long time. Now, they are in the public domain and that was our ultimate goal — that anyone and everyone should have equal access to it,” Munshi said. “We believe in disseminating knowledge and breaking barriers or restrictions on accessing knowledge.”

The IIC plans to further build its digital repository and add more books, documents and materials within the next five to six months.