New Delhi: It was in 1984 that the Indian electorate witnessed a significant shift — the emergence of women voters as a political force. As the country entered a phase of relative stability in the decades after independence and the Partition, women began asserting themselves through the ballot.

This movement coincided with the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

“After Indira Gandhi was assassinated, the voter turnout gap between men and women—which had earlier stood at 10 to 11 per cent — dropped to about 2.6 per cent,” said journalist and author Ruhi Tewari.

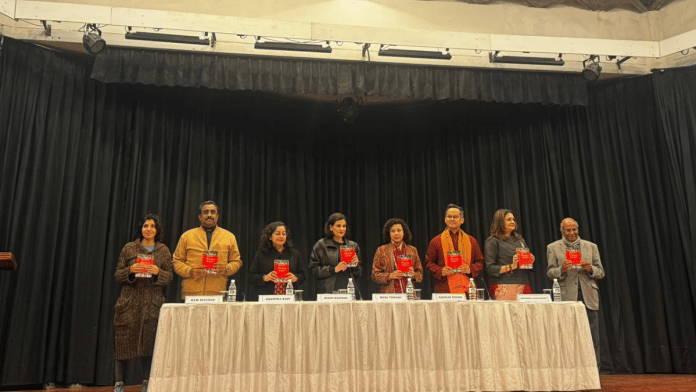

Tewari was speaking at the launch of her book What Women Want at the India International Centre on 6 January. The panel, including former National General Secretary (BJP) Ram Madhav, Secretary to the Government of India Shamika Ravi, along with Congress MP Gaurav Gogoi and Rajya Sabha MP Priyanka Chaturvedi, with journalist Nidhi Razdan as the moderator, discussed the evolving role of women as an electoral force in Indian politics.

The book explores how women shape India’s electoral landscape. Tewari travelled across states and communities to understand who women vote for and why. In the book, she asks if beneficiary schemes drive their electoral choices, or do ideology, caste and religion override gender at the ballot box.

“Two other major movements emerged in the 1990s. One was the constitutional amendments that gave women reservation and greater political participation. The other was the rise of self-help groups—both of which empowered women at the grassroots level,” Tewari said to the tightly packed hall listening raptly.

Also Read: ‘In an ideal world, there would be 10-15 Muslim women in each Parliament’: Omar Abdullah

Women as an electoral constituency

For economist and member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister, Ravi, the 2005 Bihar election presented a natural experiment. In February, no political party secured a majority, leading to a re-election in October.

“And suddenly, in October, you see that the entire landscape of Bihar’s constituencies had changed. So what changed? More women came out to vote. As a result, the incumbent was more likely to lose the election,” Ravi said.

Ravi said that’s when everyone noticed that women are voting very differently from men. “They are no longer proxies for men. They are not voting because their husbands or sons tell them to vote in a certain manner,” Ravi added.

She said a “powerful revolution” was underway in our country.

But moderator Razdan urged the panellists to share their understanding of women as an electoral constituency. Razdan pointed out that since women have emerged as a force who are decisive voters, every political party is vying for their attention. She referred to the proliferation of welfare schemes targeted at women, not only at the national level but across states.

Gogoi called these welfare schemes empowering Indian women through the “narrow lens of recipients of schemes”. He also referred to Priyanka Gandhi’s 2021 ‘Ladki hu lad sakti hu’ campaign in Uttar Pradesh.

“And it’s not that they apply online and schemes fall into their homes. They have to visit the local MLA, and that is how the arbitrage happens,” Gogoi said.

Also Read: One statement united politicians from SP, AAP, BJP. ‘It’s a war for women to be in politics’

How are women voters viewed?

Madhav argued that welfare schemes do not always work in a party’s favour.

He went on to cite an example from his political groundwork, recalling an interaction with a voter to whom he spoke about a government scheme.

“And the person said, ‘So what? It is your duty to give us this.’ We have reached a stage in politics where it’s not easy to predict voter behaviour anymore. It is affected by several factors. After burning our hands, we realised that there is no such thing as vote banks. Women voters are voting very independently.”

Each panellist offered a different perspective on how they viewed women voters.

Chaturvedi questioned the timing of welfare schemes announced for women. “If these schemes were truly meant for empowerment, they would not be rolled out so close to elections. Thank God. Women are not wedded to political parties. They decide what they are getting out of it and view these promises in transactional terms,” she said.

Chaturvedi also pointed out that while political parties frequently speak about welfare schemes aimed at women voters, they must first address women’s representation within their own ranks: “You are promising the moon and the stars, but you are not giving women tickets or adequate representation.”

(Edited by Insha Jalil Waziri)