New Delhi: At age three, Gopalkrishna Gandhi witnessed the aftermath of his grandfather MK Gandhi’s assassination. Decades later, as a diplomat, presidential aide, and governor, he bore testimony to India’s most defining and devastating moments — from the Emergency to Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination and Narendra Modi’s rise. And his grandfather’s resilience stayed with him through it all.

“Gandhi was not stopped by three bullets. He stopped those three bullets in their tracks. Three bullets of suspicion, hate, and vendetta. He did stop them, and as he stopped them, his dying word was Rama,” said Gopalkrishna Gandhi at the launch of his new book, The Undying Light: A Personal History of Independent India.

It’s a rare account by a man who saw history not from the sidelines, but from the very heart of power. His memoir intertwines personal recollections with national milestones, providing a profound perspective on the trials and triumphs that have shaped modern India.

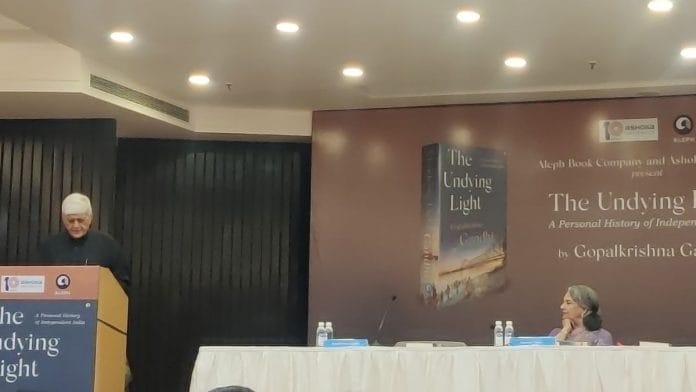

The book was formally unveiled at the India International Centre in New Delhi, opening with a keynote address by chief guest Sharmila Tagore. This was followed by a panel discussion with socio-political activist Aruna Roy, former Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission of India Montek Singh Ahluwalia, and historian and Ashoka University Chancellor Rudrangshu Mukherjee.

With his unique vantage point as MK Gandhi’s grandson and as a key figure in Indian public service, Gopalkrishna Gandhi presents a rare and intimate narrative of the nation’s journey.

“History is supposed to be conventionally understood as being impersonal, objective, bereft of subjectivity,” Rudrangshu Mukherjee said about the memoir, published by Aleph Book Company. “So ‘a personal history’ seemed to me a bit of an oxymoron. But Gopal treads a completely different path. The personal is self-effacing in this book. The history is much more salient and much more important.”

Leadership, economic philosophy

It’s a lesser-known fact that Jawaharlal Nehru wanted C Rajagopalachari to be the first president of India, and not Rajendra Prasad. Rajagopalachari was Governor General at the time and his views aligned with Nehru’s.

“Rajendra Prasad, a long-time Congress leader from the days of Champaran, had already staked his claim [to the presidency]. Vallabhbhai Patel thought it would be very unfair to deny Rajendra Babu that position,” Mukherjee said.

This anecdote is just one of many shared at the event, to shed light on the complexities of Indian politics.

Another striking moment from the memoir that was discussed at the book launch occurred during a national crisis—the evening of Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination. As Gopalkrishna Gandhi rushes to Rashtrapati Bhavan to be with the president, a significant encounter unfolds. TN Seshan, the Chief Election Commissioner, enters with an air of absolute authority.

“Suspend the elections and make me the home minister. I will bring order to the country,” Seshan said, according to Mukherjee. In that moment, Seshan stressed the need to prioritise security during a national crisis. His assertion also highlighted the raw, often chaotic nature of political life in India—an aspect Gopalkrishna Gandhi doesn’t shy away from exploring in his memoir.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia shifted the conversation to economic matters, providing a critical assessment of India’s economic trajectory, particularly C Rajagopalachari’s early critique of the country’s economic controls. In the 1950s, Rajagopalachari famously coined the term ‘License Raj’ to describe the stifling economic policies that were hindering India’s growth. He recognised the inherent flaws in a system that thwarted entrepreneurship potential and restricted economic freedom.

Ahluwalia also reflected on a well-known quote by MK Gandhi that has often been used to justify such economic controls: “Recall the face of the poorest and weakest man you have seen, and ask yourself if this step you contemplate is going to be any use to him.”

However, Ahluwalia offered a fresh perspective challenging conventional interpretations of Gandhi’s words. “What if what you’re doing to reduce poverty is actually increasing it?” he asked. “The Mahatma understood economics better than most people give him credit for,” he continued. “If you truly consider the broader picture, you could easily argue that liberalising the economy could reduce poverty more effectively.”

Also read:

Navigating violence

As hatred and bloodshed tore apart Bengal in 1946, Gandhi embarked on a peace march to Noakhali. His journey, marked by physical exhaustion and emotional turmoil, reached its tragic peak with his assassination in 1948.

“Bengal and Bihar were aflame in 1946, 1947. The fire was dispersed [by Gandhi],” Gopalkrishna said.

Frail, fasting, and physically worn, he moved from village to village with a small band of followers, hoping to extinguish the fires of communal rage with prayer, silence, and sheer moral courage.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi opens his book with a painting, depicting his grandfather traversing through Dattapara in Noakhali. Gandhi’s journey in 1946–47, through the villages of Bengal and Bihar, was a mission of atonement during a time of terrible violence and communal strife.

In the painting, a dog appears in front of Gandhi and his associates, beckoning them to follow him. Gandhi’s companions tried to dismiss the animal, but he intervened. “Don’t you see? The animal wants to say something to us?” The dog led them to skeletons, bodies hanging, death etched into the soil.

A shaken Gandhi later told a group of Muslim League members that what he had witnessed “was the very negation of Islam.”

Barely a year later, MK Gandhi himself became a victim of hatred. Gopalkrishna Gandhi recalled the day he saw his grandfather’s lifeless body at Birla House, on 30 January 1948. As a pall of gloom descended on those present, little Gopalkrishna – deposited on his mother’s lap by his sister – attempted to mimic Gandhi’s calm demeanour saying, in the playful voice of a toddler: “Sab shant ho jaiye, sab shant ho jaiye (everyone stay calm, everyone stay calm).”

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)