New Delhi: For Kuldeep Singh, a bus driver, who lost his vision in a bomb blast, ophthalmologist Dr Virender Singh Sangwan is nothing short of a miracle man. After several eye specialists failed to help him, it was Dr Sangwan’s SLET technique that came to his rescue.

It was the spirit of this ophthalmologist that brought author Rajroshan Pujari from Hyderabad to Delhi to write his biography. Unbound tells the story of a boy from Mandola, Haryana, who could not get into medical college on his first try. But he went on to make ‘premium’ eyecare affordable for the masses with his innovations. The biography was launched recently at the India International Centre. And the packed hall was a testament to the doctor’s popularity.

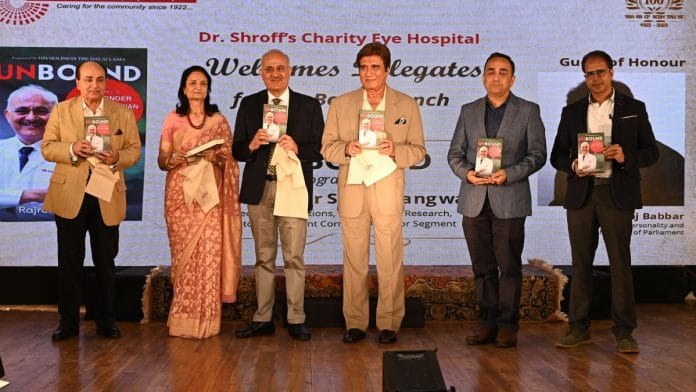

The book was unveiled by actor and former parliamentarian Raj Babbar. The speakers included Dr Umang Mathur, CEO of Dr. Shroff’s Charity hospital, Vipin Buckshey, optometrist and founder of Visual Aids Centre.

“Being a son of a farmer, not knowing English, going to Delhi, learning and scaling to finally become an MBBS, instead of trying to recover his student loans, he joins Orbis flying hospital—taking ophthalmic treatments to developing nations. So that whole journey was interesting for me,” said Pujari

The Flying Eye Hospital by Orbis is the world’s only ophthalmic teaching hospital onboard an aircraft. And Dr Sangwan’s contribution to this global training project is remarkable. Orbis is an international not-for-profit dedicated to the cause of eye health worldwide.

Also read: Dwarka RWAs sending fire safety manuals on WhatsApp. What Delhi needs is more fire stations

An easier process

The bomb that went off in Kuldeep’s hands burned both his corneas. Restoring his vision required “a novel technology and the hands of a dexterous surgeon”, writes Pujari in Sangwan’s biography.

Simple Limbal Epithelial Transplantation or SLET was the ‘affordable solution’ for patients like Kuldeep. Dr Sangwan’s technique did away with the expensive lab procedure and brought down the cost of surgery from “somewhere around Rs 5 lakh to Rs 50,000” in 2010.

SLET is a surgical procedure designed to restore the corneal surface in patients with limbal stem cell deficiency (LSCD). Before Dr Sagwan’s innovation, surgery for LSCD required an expensive specialised lab. Stem cells from a healthy eye needed 14 days in the lab before they could be transferred onto the patient’s eye.

With SLET, stem cells can be taken directly from the healthy eye of the patient or from a donor’s eye and put on the damaged eye. This eye acts as a laboratory to culture the limbal stem cells for the cornea. The surgery could now be completed in a single sitting.

Also read: Delhi’s mango lovers brave the heat, buy Rs 4,000 buffet. It turned into a sour affair

The next corneal revolution

Listing yet another achievement of Dr Sangwan, Dr Mathur mentioned his work with the artificial cornea.

“Just when you think he might be done, he casually sets off to develop an artificial cornea. Because donor shortages shouldn’t limit sight,” said Dr Mathur. When it comes to corneal donations, the dependency on voluntary eye donations is still a limiting factor. And while there are artificial corneas on the market already, Sagwan’s team is developing ones that don’t require sutures and allow for “simpler, less invasive implantation”.

Anil Tiwari is a chief scientist who followed Sangwan from Italy to be a part of his team. “His (Sangwan’s) name is enough to leave everything and follow him to a lab in Daryaganj, Delhi,” said Tiwari to ThePrint.

Dr Sangwan highlighted the areas where Indian innovators need to step up—high value items like diagnostic equipment or surgical instruments, or microscopes. “And it’s not technically very difficult, that’s a huge field,” said Dr Sangwan.

To this end, the ophthalmologist is building a fundamental base of Indian innovators and connecting startups in the Indian medical space, mentoring them, and directly investing in them.

Dr Sangwan and his team are close to their ‘Eureka’ moment with the sutureless cornea.

“Everyone unanimously understands the impact of the technology,” said Pujari, “Because if it comes into play, what it means is all corneal donation would be eliminated’.

The author is an alumna of ThePrint School of Journalism.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)