New Delhi: Indian queer fiction is emerging as a “transformative force” in contemporary culture. And while precious few queer stories are being told, a lot of them are about young, pretty people falling in love, said author Santanu Bhattacharya at the India launch of his book, Deviants.

“The young couple [in popular queer narratives] faces some challenges but eventually gets together. That has its place, and people need hope, but there is more to queer life than that. I don’t see it anywhere—definitely not in our subcontinental context,” said Bhattacharya in conversation with lawyer Rohin Bhatt.

The author was mostly referring to romances such as What If It’s Us and Red, White, & Royal Blue that are currently popular in the West. He added that the West has an AIDS canon as well as historical figures such as Oscar Wilde and Alan Turing, who have now become part of the global history of queerness. But these are largely missing from the history of South Asia.

After a few flashes of brilliance such as R Raj Rao’s The Boyfriend, Jerry Pinto’s Murder in Mahim, and Arundhati Roy’s Ministry of Utmost Happiness, the genre dries up, giving way to narratives that feature queerness but don’t centre it. While names such as Ruth Vanita, Saleem Kidwai, and Agha Shahid Ali are offered up in desperation at the mention of queer writing in India, they remain at the margins.

Queerness in Indian fiction is still on its journey to the mainstream, something that happened in the West during the 2010s.

The storytelling

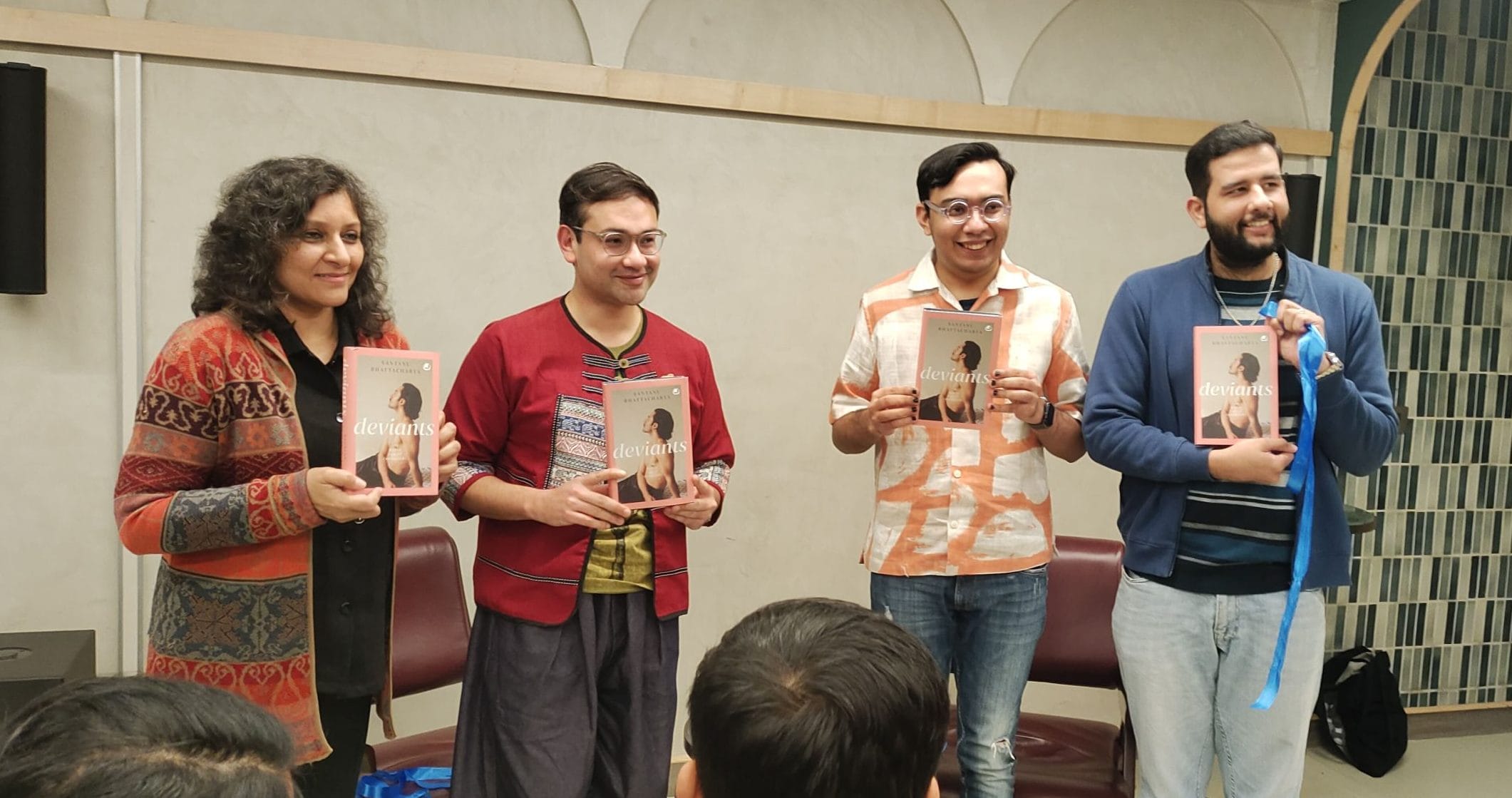

The cosy hall at the New Delhi LGBTQIA+ Centre was at capacity on 27 January, with writers, editors, and creatives making up the 40-odd attendees.

Bhattacharya said that he knew what he didn’t want his novel to be. He didn’t want to explore the gay man’s archetypal religious tussle, the fretting mother, or the big coming out scene. Instead, he wanted to look at queerness in family histories and tell the stories that deviate from the lines of lineage.

The discussion revolved around the theme of ‘Writing Queer Stories’ and the ideas of shame, pride, love, heartbreak, and self-knowledge that accompany it. Rohin Bhatt, an author himself, said that the theme of shame is universal in queer storytelling.

“Storytelling is a radical act in itself, of being able to tell your life in all of its glory—and all of its shame, as it were,” said Bhatt.

Getting access to sexual health resources, the conversation highlighted, is also an experience marked with anxiety and shame for many queer people. Bhattacharya shared a mortifying encounter about getting tested for HIV non-anonymously, owing to his euphoria after the Section 377 judgment. But when his report couldn’t be found at the hospital, the staff and doctors alike were shouting at each other nonchalantly, “Where’s the HIV report, where is sir’s HIV report?” Bhattacharya could feel all the other patients staring at him.

Bhatt noted that conversations around AIDS have also come to be ignored in modern fiction.

“The Naz Foundation was one of the foremost organisations after the AIDS Bhedbhav Virodhi Aandolan that talked of queerness through the lens of HIV—a conversation that was drastically important, but also is often missing in modern narratives,” he said.

Also read: ‘I Want A Boy’—4 words Dr Aruna Kalra kept hearing even in delivery rooms

Queer youth and elders

Deviants revolves around three men—16-year-old Vivaan, his uncle Mambro, and grand-uncle Sukumar.

Characters such as Elio in Andre Aciman’s novel Call Me By Your Name or Jia-han in the 2020 film Your Name Engraved Herein often run into the problem of thinking in an old man’s language. Bhattacharya had to understand the thoughts, feelings, and struggles of a gay teenager in India today.

The exercise also highlighted the distance between queer youth and elders.

“In any marginalised community, in queers, in women, where the leaps are quite radical from one generation to another, it’s very easy to feel some sort of resentment for how much the younger people have. And I hope that my book is able to show that every generation has its own journey—how we support each other in that process is important,” Bhattacharya told ThePrint.

This is further complicated by the absence of a “template”: the youth doesn’t know what it means for a South Asian queer person to grow old. That is why Bhattacharya, while he’s excited about what the new generation brings to the table, is more keen on hearing from the one that came before.

“For me, it’s not just about expanding the space to have more younger people. I want to hear from older people because we’re not growing younger—we’re growing the other way.”

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)