New Delhi: When professor and author Vibhuti Ramachandran was deciding the cover of her book Immoral Traffic, she didn’t look for an illustrator or commission original artwork. She dug through news reports and found a photograph taken years ago by a Mumbai-based photojournalist, Pramod Dethe, for Hindustan Times in 2008. An image, so familiar that it almost disappears into the everyday writing of crime reporting.

In the photo, shot inside a police vehicle, sit six to seven women, all rescued during a raid. Their faces are hidden behind bright, colourful dupattas, green, blue, orange, pulled tightly across their heads. Some use their hands as an extra shield to ensure their identities remain concealed. It is the kind of photograph routinely shared by the police with the crime reporters after “rescuing” women and arresting men accused of trafficking or prostitution, under the common, unremarkable, and rarely questioned Immoral Trafficking (Prevention) Act. This very ordinary photograph became the point of Ramachandran’s book.

“That moment, where the girls and women are in the police van, inaugurates an entire series of punitive forms and processes of intervention. The book starts with that very moment of raid and rescue,” Ramachandran said at the launch of her book at India International Centre on 18 December.

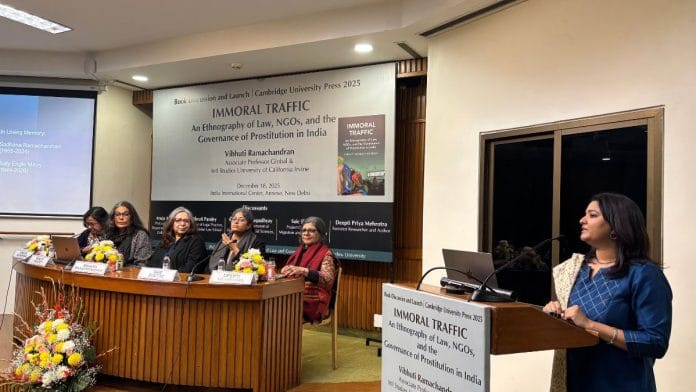

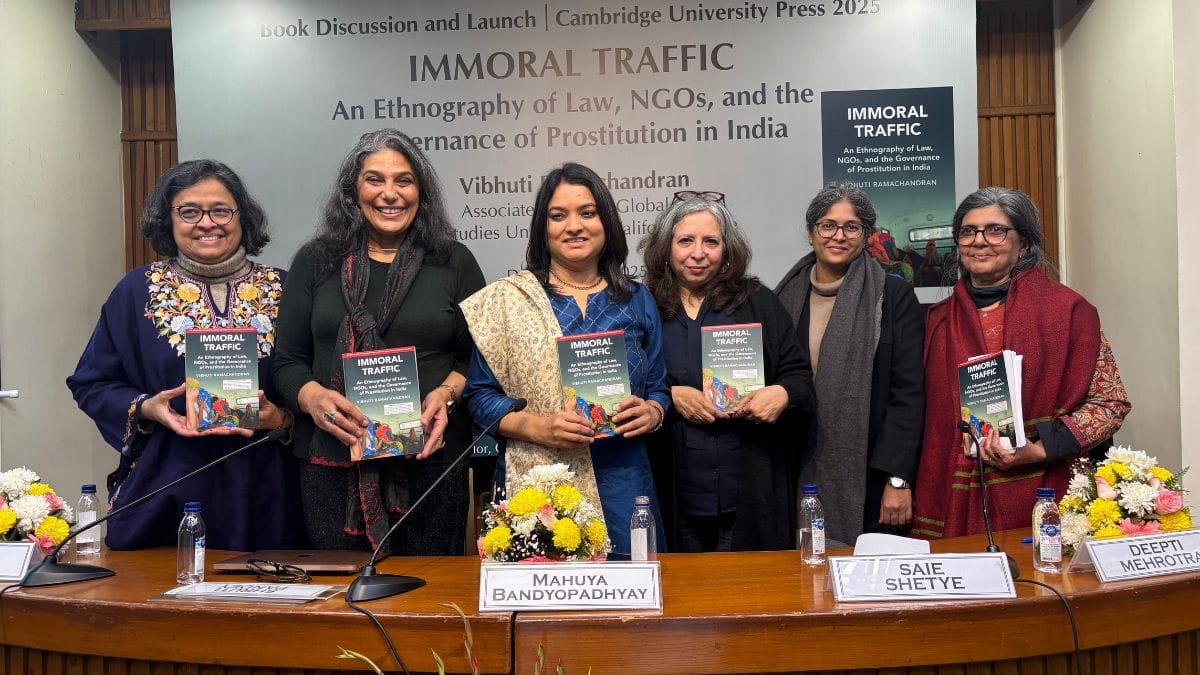

Ramachandran, associate professor of global and international studies at the University of California, Irvine, was joined by a panel of scholars and researchers who have long worked on gender, law, migration and incarceration. The discussion was headed by Anuja Agarwal, professor and head of sociology at Delhi University, Shruti Pandey, professor of legal practice at Jindal Global Law School, Mahuya Bandyopadhyay, professor at IIT Delhi, Saie Shetye, project coordinator at Migration and Asylum Project, and feminist researcher and author Deepti Mehrotra.

At a time when anti-trafficking efforts are often measured by the number of raids, rescues, and convictions made by the police and courts and the data shared by the state police units and Home Ministry, Immoral Traffic asks: What happens after a raid? What happens to these ‘so-called shelters,’ these protective homes where these women are taken after a raid?

Ramachandran critiques the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act and the broader anti-trafficking measures in the book, which she says are built on moral assumptions rather than women’s lived realities. The law frames women primarily as victims in need of rescue, while leaving little space for agency, consent, or economic choices. Through courtroom observations and interviews, the book shows how women are repeatedly asked to fit into categories; it is either a ‘genuine victim’ or a ‘liar,’ or somebody who is ‘coerced’ or an ‘immoral woman.’ These categories have consequences for where the women are sent next.

The book also talks about how trafficking law in India is shaped less by women’s needs than by anxieties around sexuality, migration, labour, and family honour. Women are rarely treated as workers or decision makers; instead are categorised as victims. Ramachandran’s research is multi-sited, from Delhi to Mumbai. It focuses on the interactions between NGOs, legalities, state agencies, and the women who experience their interventions.

Left with only two choices

If a woman denies doing sex work, medical reports, such as the “two-finger” test, are used to discredit her.

As the speakers sat in a room with people of all ages, they analysed and discussed the book chapter by chapter. Speaking on the chapter titled “Inquiries”, Deepti Mehrotra focused on magistrate-led interrogations that decide a rescued woman’s immediate failure. These inquiries, held in chambers next to special courts, are meant to assess whether a woman should be sent to a shelter home or returned to her family.

“There are only two choices,” Mehrotra said. “Protective custody or familial custody. There is no space where she is treated as an autonomous individual capable of living independently.”

Far from having a supportive environment, these rescued women are looked at with suspicion during such inquiries. There are questions raised about families, origin, and work around moral judgment, guilt, and shame.

If a woman denies doing sex work, medical reports, such as the “two-finger” test, are used to discredit her. If she claims she chose the work, that agency itself becomes proof of deception, Mehrotra said.

Saie Shetye has worked closely with anti-trafficking NGOs and court processes, with Ramachandran by her side. Drawing from these observations, Shetye questioned the assumption that high conviction rates necessarily translate into justice for trafficked women.

In most of these cases, the woman never testifies at all. Convictions happen through police witnesses, panchnamas, and the accounts of NGOs. A woman’s voice is almost absent from the legal process, Shetye said.

Of shelter and confinement

“The state is not comfortable with women who fall outside family and marriage”

If a court decides women’s fate, shelter homes enforce it. Analysing the final chapter on “Shelters”, Mahuya Bandyopadhyay examined these institutions through the lens of incarceration.

What is framed as “sheltered detention,” Bandyopadhyay argued, is justified as care, but operates as confinement. Women are denied freedom of movement, consent, and the right to exit, often for prolonged periods.

These shelters interrupt the mobility that many women rely on for their livelihood. Women are not informed when they will be released, and they live in a constant state of uncertainty.

For sociologist Anuja Agarwal, ‘rescue’ is often less about protection and more about discipline and control.

“The state is not comfortable with women who fall outside family and marriage. Rescue becomes a way to return them to control, which is either the family or institutions. It doesn’t recognise them as independent individuals,” Agarwal said.

Speaking about “resistance to raids,” Agarwal recalled a story she said she would never forget. According to media reports, the incident took place in Pachi ka Nagla village in Rajasthan’s Bharatpur district.

“This was back in 2017, when the police raided one of the locations I did my field work in. Four women, in order to escape the raid, jumped into a pond, and two of them died. That is the consequence of a police raid. This is what people can do to escape police intervention.”

(Edited by Ratan Priya)