New Delhi: Thirty years ago, Visalakshi Ramaswamy had a realisation about her beloved Chettinad: “Many things were just disappearing in front of my eyes”. Something had to be done.

Chettinad, a culturally rich pocket in Tamil Nadu’s Ramanad district, is where the Chettiyar community comes from. Known across India as bankers and mercantilists, their money has travelled. Now, a new exhibition in New Delhi called ‘Chettinad: An Enduring Legacy’ is trying to bring their culture out of their geography. It’s like bringing the kuzhi paniyaram out of their kuzhi (a trademark Chettinad dish of steamed dumplings served in a platter of tiny pits).

And so, in 2000, Ramaswamy founded the M.Rm.Rm Cultural Foundation to revive Chettiar crafts, textiles, and architecture. She went on to win the IBCN Award for Entrepreneur with Social Impact in 2015 and the Hindu World of Women Award in 2018.

An organisation whose motto is ‘Research, Document, Revive’, M.Rm.Rm is one iteration of the many attempts by small communities across India to find a place in the congested tapestry that constitutes the country’s composite culture. This is about survival. And it has led curator Ramaswamy to open her exhibition at the India International Centre. Indeed, everyone must “do their duty”, she says.

Also Read: India lost 80% film heritage by 1950s. These workshops preserve what’s left & screen them

An appeal to young Chettiars

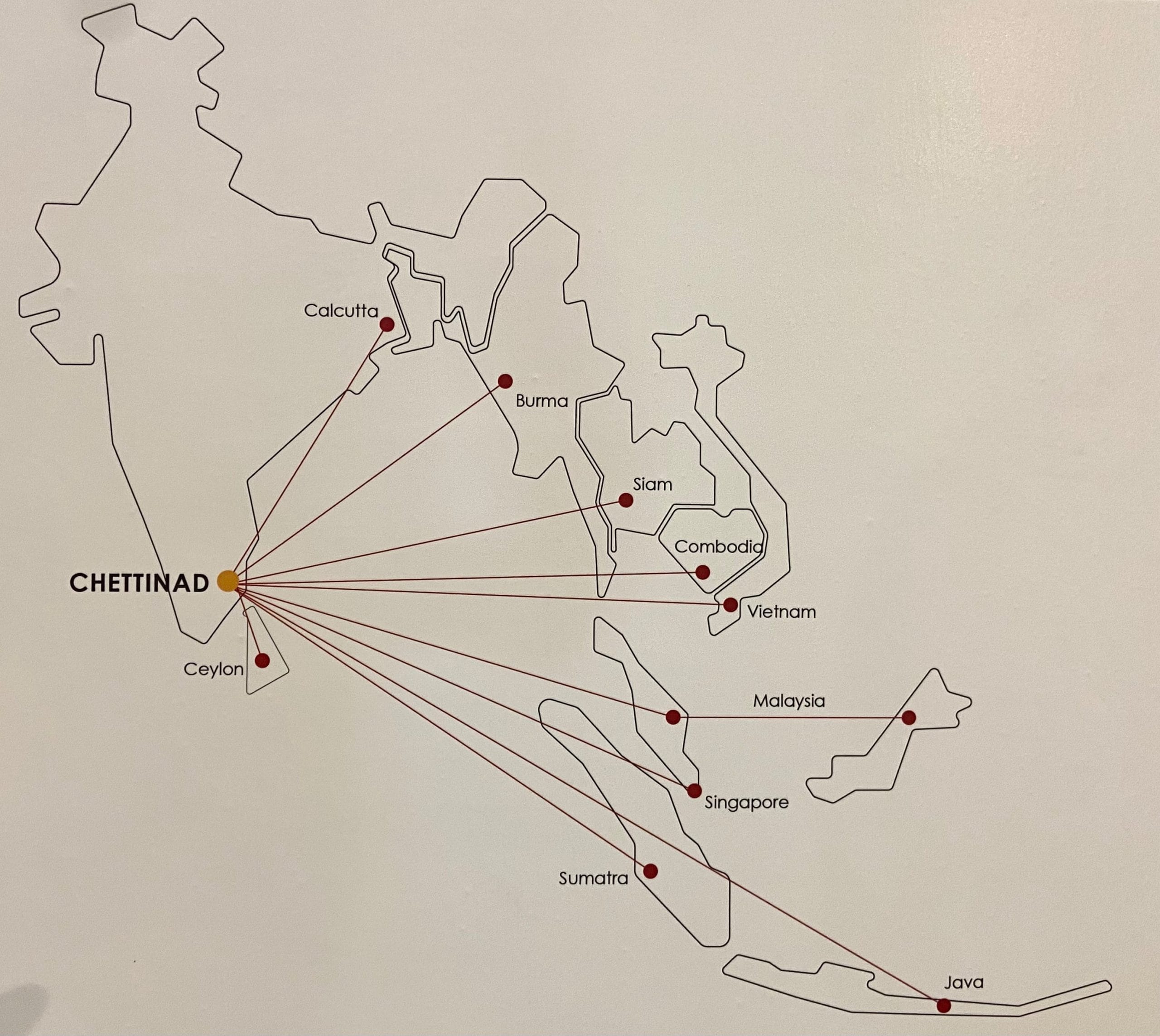

At the centre of the exhibition space lies the main information board, with a map of South and Southeast Asia. Marked on it are Vietnam, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Singapore—Chettiar people and culture are found in all these places. The concept note for the exhibition explains that it was in the context of imperialism that Chettiars relocated to British colonies bordering the Indian Ocean to establish financing firms.

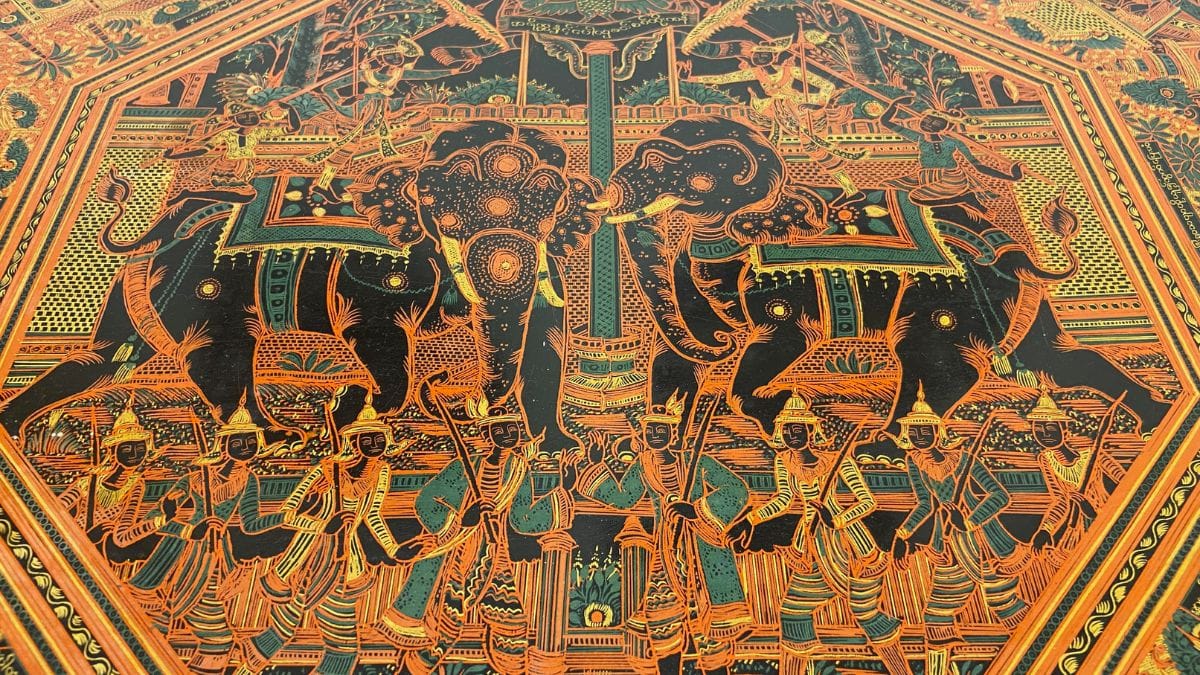

And so, Ramaswamy’s exhibition recounts how Chettiar mercantile communities in erstwhile Burma would periodically send lacquerware back to the Chettinad homeland. These painted objects are collectively known as maravai in Tamil and have generally been made of wood or woven rattan and horsehair. Visitors can see some beautiful examples at the exhibit.

The audience learned that these pieces were incorporated into wedding ceremonies in Chettinad, where they would become part of the bridal trousseau. “This use of lacquerware shows the cross-cultural influences that made this community unique,” reads an information board at the exhibition. Elsewhere in the exhibition hall, there are endless artefacts from Chettinad on show, such as ornate tables, coffee containers, and cooking equipment.

One of Ramaswamy’s guiding principles is that “you should never forget where you came from”. This is a message directed largely at young Chettiars, whom she exhorts not to forget their roots. “If you have lost everything, there is nothing to go back to,” she stresses.

Ramswamy’s showcase, however, couldn’t pull as many youngsters. Alive to the apathy among some young people toward cultural preservation, she emphasised that it is upon the previous generation to leave a cultural legacy for their young successors. This piece of advice seemed to be directed toward the older attendees, but, like everyone else present, they would have struggled to hear her elaborations due to faulty microphones.

Even though M.Rm.Rm was established with the express intention of preserving the past, there is a sense from Ramaswamy that a combination of the past and the present is required to prepare for the future. In her own words, “change is the only permanent thing,” but equally, we must “not lose the good things we already have.”

M.Rm.Rm has had considerable success in its attempts to protect Chettiar culture. Pamphlets and information boards mention the foundation’s design directory of the Kandanghi sari, which meticulously documents the weave details of more than 100 saris. The deep red, orange, and yellow hues of these garments are on view at the exhibition. Craft products from M.Rm.Rm are also sold at their store, Manjal, in Chennai.

The foundation has many hurdles to overcome, though. In the past, egg plaster would be laid in five layers and smeared on the interior walls of Chettiar houses to guard against South Indian heat. Now, the foundation struggles to locate masons who can help revive the technique. Stencil paintings also adorned the walls of Chettiar houses, but today, most traditional artists have moved into other lines of work. The foundation admits that it is struggling to stem the tide.

Also Read: Hyderabadi, Chettinad, or Kolkata — Biryani is for everyone. Politics is the elaichi

The art of reviving

One of the foundation’s greatest successes has been the empowerment of women in Chettinad, a cluster of 75 to 100 villages between Trichy and Madurai in southern Tamil Nadu. Chettinad’s Palmyra basketry, known as kottan, had diminished over time. Now, the beautiful bead- and crochet-work-adorned baskets are back due to the foundation’s efforts, which is evident in the stunning purple kottan display at their IIC exhibit.

Ramaswamy’s organisation began teaching the technique of kottan production to the women of Keelayapatti village, and now operates in four other Chettinad villages. More than 100 women are involved in the project, and each is subsequently in a better position to earn a stable income.

The foundation stresses the fact that these women have been able to expand their skills and experiences through craftwork. For instance, they learn how to market their products and manage financial accounts. By travelling to exhibitions and meeting a wide range of craftspeople from other states and nations, they now have access to a world beyond their immediate locality. International organisations have also recognised the work done by the foundation. Since 2004, these trained women artisans have received the UNESCO WCC Award of Excellence seven times.

The benefits of the foundation’s work are being felt across generations of women. Since the inception of M.Rm.Rm and its workshops, more girls have been attending school in Chettinad.

Ramaswamy has come a long way since 2000. Initially, she had a private exhibition in her home, where people could visit by invitation only. Now, this private collection draws in audiences as a formal showcase in the country’s capital. But for Ramaswamy, this is “only the tip of the iceberg”.

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)