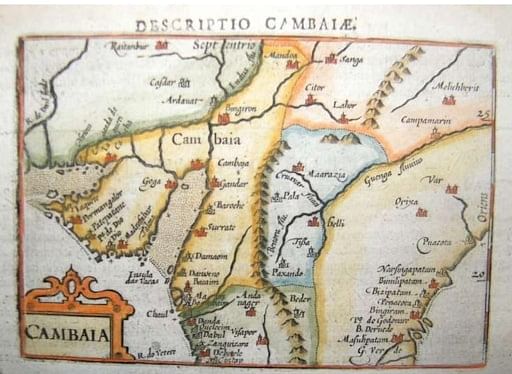

New Delhi: Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata ports have been the nerve centres of India’s trade and commerce for centuries, and most Indians tend to believe that would have been the case since forever. Except not. It was a port in Gujarat that was the gateway to India’s trade lines for more than six centuries. Cambay thrived as one of the world’s leading commercial hotspots along the Indian Ocean.

Historian Neera Agrawal highlighted this fact during her recent talk titled The Merchants of Cambay: Trading World of Cooperation, Confrontation, and Conflict at the India International Centre. However, the talk turned out to be a 45-minute monologue with a thin audience of 12 people — historians, history buffs, and a lone history student. Some appeared bored and sleepy.

But nothing deterred Agrawal. Ignoring the boredom in the room, she shared her extensive historical research on Cambay – the town that emerged as the Indian subcontinent’s foremost port, buzzing with people and products from across the globe – from the late 900s to the 1500s. Agrawal’s research focuses between 1736 and 1818, a period of three-partite cooperation.

Agrawal didn’t limit her lecture to the commercial aspects of the town and went on to describe how the port became the place of exercise of power between the Britishers and the local merchants.

“There were Englishmen who wished to dominate and shift the terms of trade in their favour, and on the other hand was the society represented by the Nawab, the local merchants and the Marathas who did not intend to let go of their political commercials. The stage was set for cooperation, confrontation and conflict,” Agrawal said.

A two-way road

Discussing the workings of trade and domestic politics Englishmen faced back then, the historian said the East India Company ensured the participation and cooperation of the big local merchants, brokers, and dealers. In return, they were offered financial and physical protection.

When English traders faced challenges in the cotton centers due to language and space issues, they sought cooperation from local powers like Nawabs, the big merchants, and the Marathas. It was crucial for the expansion of trade, their survival, and economic growth.

“The merchants needed protection from the exploitation of the Nawab and constant threats from the Marathas,” Agrawal said, emphasising how English understood the loophole in the internal ecosystem.

Between the East India Company and merchants, it was a two-way road, but, time and again, the Nawab protested to showcase their presence. By blocking the routes and introducing clearance certificates, he attempted to hinder the smooth functioning of the trade. He remained astute, exploring opportunities whenever they arose. Hence, there was a constant tiff for dominance in Cambay.

“It was a cat and mouse struggle, with one side gaining ground and the other yielding,” Agrawal said, with a smile.

Meeting the Nawab

Agrawal’s talk offered a peek into Cambay’s past that had two key elements, presumably unique to urban modern centres: a flourishing multicultural population, and an understanding administration ready to extend help to profitable business enterprises.

During the mid-18th century, Cambay fell into neglect, and its fortunes began to wane. The city grappled with geographical challenges, including receding seas, shifting sands, and extensive silting, further exacerbating its decline.

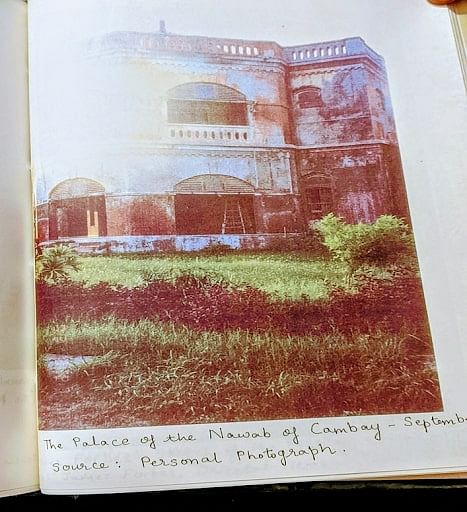

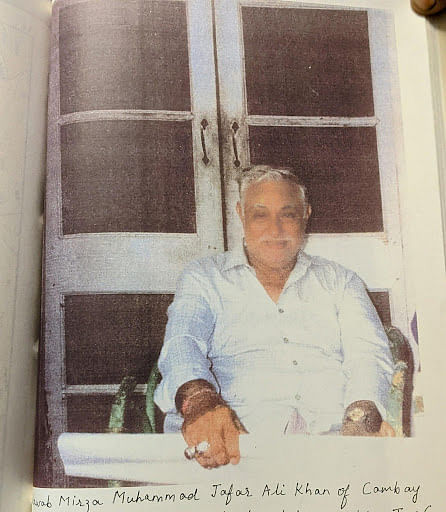

The last Nawab of Cambay was Nawab Mirza Muhammad Jafar Ali Khan, whom Agrawal had the opportunity to meet in his “dilapidated palace in a sad financial state.”

“When I entered his premises, the palace was in a terrible space. He put up a big show and made me wait in the corridor for a long time. And, when I saw him, I wondered where the glory was. Where is the aura? But he was very courteous,” Agrawal told ThePrint.

The Nawab didn’t seem too happy with his current status; he expected to wield some power even in small matters of Cambay. He wasn’t sad about losing his wealth; he was sad about losing authority, said Agrawal.

Nawab Mirza Muhammad Jafar Ali Khan died in 2012 without leaving an heir, and the title of Nawab of Cambay was lost in the history pages.

(Edited by Prashant)