New Delhi: The decline of Indian civilisation did not begin with conquest alone; it began when curiosity, realism, and institutional memory were drained away. This was the unsettling proposition that hung in the air at the launch of The Decline of the Hindu Civilisation: Lessons from the Past, a book by Shashi Ranjan Kumar, the secretary of the Union Public Service Commission.

“A sense of history is essential to know what India was, and therefore what India is capable of — where India faltered, and what should not be done again,” said Kumar.

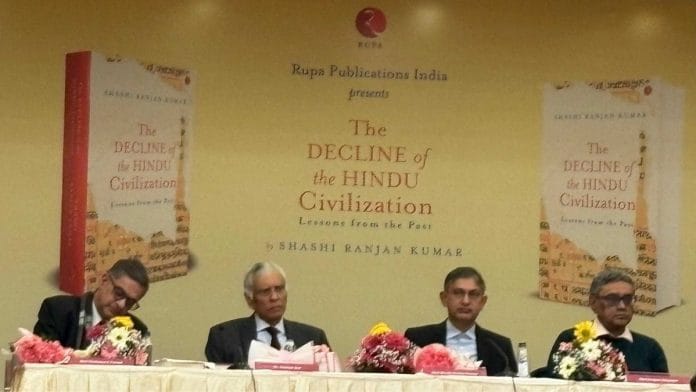

For the book launch, scholars, economists, writers, and public intellectuals converged at Delhi’s India International Centre (IIC) to examine some of the most difficult questions about India’s civilisation journey. The discussion was moderated by Chaitanya K Prasad, a retired civil servant, author and commentator, with journalist and former Rajya Sabha MP Swapan Dasgupta, political economist Gautam Sen, and author Amish Tripathi joining virtually.

The discussion challenged the audience to rethink how and why one of the world’s oldest living civilisations began to falter. Speakers drew references from 12th-century Kashmir to Mughal Delhi, from Nalanda’s ashes to modern universities.

Author Kumar said that the decline was not accidental, but cumulative, driven by the erosion of institutions, the abandonment of realism in statecraft, and a growing indifference to power, geography, and history itself.

“The scale of destruction — material, institutional, intellectual — is still inadequately assessed and often discussed only reluctantly,” he said.

An inward turn

Kumar took the audience back nearly a thousand years to 1140 CE in Parvarapura, modern-day Srinagar, where a vibrant cultural gathering took place. Alankara, a Kashmiri royal court official, hosted an evening to celebrate his brother’s epic on Shiva, Srikranti Charita. Thirty-two scholars, including Ruhyakka — the Makha’s teacher and a leading political authority — and Kalhana, author of Rajatarangini, came together.

Philosophers, poets, grammarians, aestheticians, and even an architect gathered from across the region, reflecting Kashmir’s rich intellectual life.

Ten years later, mathematician and astronomer Bhaskara II, in present-day Maharashtra, composed Siddhanta Shiromani, a rare fusion of mathematics and poetry. His verse from Leelavati, a 12th-century mathematics treatise, illustrates the blend perfectly:

“The necklace of a young girl in the tussle of pleasure broke. One-third of the pearls fell on the ground. One-fifth on the bed. One-sixth were taken away by her beautiful fair. One-tenth collected by her lover. And one-sixth remained on the thread. O mathematician, tell me, how many pearls were on the necklace?” said Kumar.

Meanwhile, in Bengal, Jayadeva’s Geet Govind combined delicate imagery with emotional depth, celebrating the eternal drama of Radha and Krishna.

But this golden era came to a tragic end. After the fall of King Jayasimha of the Lohara dynasty, Kashmir spiralled into chaos and foreign rule, silencing its scholars. The defeat of Prithviraj Chauhan in 1192 opened India to invasions that destroyed great centres like Nalanda and Vikramshila. By the 14th century, much of the region was under foreign control, and intellectual traditions faded — except in Kerala.

Kumar said that the scale of destruction — of institutions, temples, and learning — is still under-appreciated, partly due to political reluctance. This decline marked India’s long intellectual retreat just as Europe’s universities flourished, setting the stage for the Renaissance.

“Reflecting on India’s military failures, I was struck by one paradox: while Indian texts promoted deception and covert tactics, such strategies were rarely used effectively. The Marathas’ guerrilla warfare was a rare success, highlighting a lost realist tradition after the 14th century. The Arthashastra, once a cornerstone of political thought, had vanished from influence, replaced by an emphasis on moral kingship over pragmatic statecraft,” said Kumar.

India’s inward turn also extended to geography. Despite extensive travel and trade, there was little interest in mapping or understanding foreign lands. Kumar said that unlike China and Japan, India remained open but inward-looking, slow to respond to Western threats. The 1766 Mughal mission to Britain sought only military ties, not knowledge transfer.

Also read: ‘There is no crash course in secularism. it should be a way of life,’ says Javed Akhtar

‘Purvapaksha’

Dasgupta placed Kumar’s argument within a larger truth: civilisations do not survive on culture alone. They need power, memory, and the will to defend themselves.

“You cannot nurture a civilisation if you have a hostile state power present,” he said. “The importance of a sympathetic and benign state power is fundamental.”

Drawing from the book and from his own reading of the 19th and early 20th-century Indian thinkers, Dasgupta noted that questions of decline preoccupied figures as varied as Swami Vivekananda and RG Bhandarkar. What has changed, he said, is that history itself was removed from public reach. “History was taken out of the hands of ordinary people and handed over to abstractions — modes of production, theoretical models — with no life or soul.”

For Sen, the battle of history is neither academic nor polite. He said that global academic ecosystems actively marginalise alternative readings of Indian history, while producing high-quality narratives that omit or dilute the civilisation core.

“If you read the preface by William Dalrymple, you’ll see the constellation of influential figures supporting him — a level of backing we can only dream of. While we occasionally secure funding, it pales in comparison. This is a well-coordinated, systematic effort, stretching from Rutgers to Oxbridge, aimed at undermining the new historical narratives advanced by voices like Sanjay Sanyal, Meenakshi Jain, etc. Unfortunately, in this battle over history, we are largely losing the narrative war,” said Sen.

The last thousand years, Tripathi argued, should not be read only as a chronicle of defeat.

“With the same set of facts, we can say it was the greatest resistance in human history. Every other ancient culture that faced these invasions died out. We are still here,” he said.

He pointed to repeated episodes where Indians aided their own conquerors — from financiers backing Robert Clive to soldiers fighting power against fellow Indians.

“Among the greatest temple breakers in human history was Malik Kafur — a Hindu convert. Internal disunity weakened us far more than numbers ever did,” Tripathi said.

He also talked about the absence of purvapaksha — calm, rigorous analysis of adversaries.

“Jagat Seth, one of the foremost businessmen of the 18th century, funded Robert Clive’s army. In fact, some Indian merchants supported the British drug-smuggling operations during Queen Victoria’s Raj, running opium into China — a complicity that ultimately inflicted tremendous harm on India itself,” said Tripathi.

(Edited by Aamaan Alam Khan)