New Delhi: If you were asked to imagine a blind person, how would you picture them? Prabhjot Ahluwalia, a theatre facilitator, posed this question to a room full of students and faculty members at Delhi’s Kirori Mal College. He paused, then offered an answer: “You probably imagine a man wearing black goggles, holding a stick, or moving his hand in the air to find direction.”

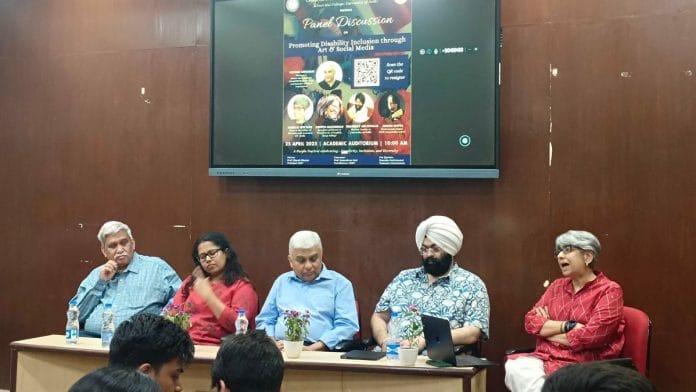

The Centre for Disability Research and Training at Kirori Mal College recently organised a panel discussion titled ‘Promoting Disability Inclusion through Art and Social Media’. It explored how society views disability, how it is represented in art, and what individuals can do to normalise it and advocate for accessible facilities for disabled people.

“We need to stop the stereotype of portraying disability and disabled people in a particular way,” said Ahluwalia, who teaches theatre at the University of Delhi. “A blind person carries out daily tasks just like anyone else, so why do we need to add dramatic music or distinct sound effects every time they appear on the screen?”

Ahluwalia was joined on the panel by Score Foundation CEO George Abraham, IIT Delhi professor Angelie Multani, and Delhi University professor Aneeta Rajendran. Experts from academia, art, theatre, and music formed the audience for the event.

Ahluwalia spoke about how he cast a visually impaired person in the role of MK Gandhi in one of his plays. Many wondered whether the role could be performed by the actor, and Ahluwalia faced constant refusals and scepticism.

“That day, I realised that if I am not able to make it happen, it means I am not capable enough to bring that vision to life. It’s not their fault that they can’t see. It’s my failure that I haven’t yet found a way to move it forward,” said Ahluwalia.

Not enough progress

Disability activist George Abraham said that it is not his blindness that hurts him, but the world’s response. Certain experiences in life make him feel disabled in every sense, he added.

Abraham recalled an incident during his travels in the UK. While booking his ticket, he had mentioned that he would require assistance on account of his disability. But when he checked in, the staff offered him a wheelchair.

“I said I needed assistance because I am visually impaired, not physically disabled. I am not locomotively challenged,” he said. It wasn’t the last time he faced such negligence.

Abraham emphasised that accessibility should not be limited to ramps and wheelchairs. “Every disability requires a different kind of support and infrastructure,” he added.

The event was filled with personal stories from the panellists, which helped expose the deeper gaps in society, not just in terms of infrastructural problems but also ableist attitudes and stereotypes. While positive changes are emerging in literature, art, and society at large, the progress, according to Multani and Ahluwalia, still feels too slow.

Also read: 24, Jor Bagh gets its last hurrah—the art space that became a metaphor for Delhi

Steps toward change

Angelie Multani, who is Dean at the Office of Diversity and Inclusion at IIT Delhi, stressed casual ableism in our everyday speech.

“‘Raise your hand’, ‘Stand up’, ‘Can’t you hear me’, ‘Are you mute’—these are phrases we often say or hear in everyday conversation,” said Multani. “But do they sound the same to everyone? For someone who doesn’t have hands, can’t hear, or can’t speak, these casual expressions relate directly to their lived disabilities. What we treat as figures of speech are, for some, very real and significant parts of their lives.”

Multani shared an anecdote from her classroom. After the Covid-19 pandemic, when wearing masks had become a part of everyday life, she would wear one while delivering her lectures. She noticed that a boy in her class would wear earphones and keep staring at her intently. “I thought to myself, the new generation is always glued to their headphones and phones,” she recalled.

One day, the boy asked her to remove her mask. She discovered that he was hearing-impaired. He used a hearing aid but still found it difficult to hear her clearly. And because she was wearing a mask, he couldn’t read her lips to take notes.

Even as the world evolves toward inclusivity, Multani emphasised that it is crucial for people with disabilities to raise their voices too.

“The person who wants the change, whose needs are different from others, must raise their voice. It is essential for bringing change in society.”

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)