New Delhi: Sundar Pichai, Satya Nadella, and Indra Nooyi are triumphs of the American dream. But closer to home, that’s secondary. In India, they’re through and through Indians—the nation’s gleaming social, cultural, and political resources.

This appropriation reveals the country’s changing psyche and the realisation that NRIs (Non-Resident Indians) and POIs (Persons of Indian Origin) need to be inducted as part of India’s growth story. At a talk held at Prime Ministers Museum and Library (formerly Nehru Memorial Museum and Library) on 11 June, researcher Smita Tiwary traced the history and policy initiatives that have led to the Indian diaspora coming into their own.

According to Tiwary, there has been a noticeable shift in perception. Pre-independence, those who made their way out of British-ruled India were primarily indentured labourers. They were consequently seen as victims of the regime: products of forced migration.

“Post-2000, the government became proactive. The concept of nationalism shifted and grew ‘de-territorialised’. The idea is that everyone is India,” said Tiwary to a group of researchers and academics. “They are now treated as cultural ambassadors and representatives of India’s soft power. We tend to have good relations with countries where the diaspora is successful.”

Government stance: From passivity to ‘duty’

When India gained independence, notions of nationalism were based on territory.

“Only those who were residing in India represented India and its welfare. Only what benefitted them were the concerns of the country. Indians faced various problems, including racial discrimination, in countries like Uganda, Kenya, and South Africa,” said Tiwary.

“But the response of the government was passive.”

Although, over the years, governments modified their policies in accordance with changing identities and social contexts.

An instance of this was when the oil-rich Middle East became a central aspiration for Indians in the mid-1970s. The government then felt “duty-bound” to protect the interests of its citizens—who went as labourers on short-term permits—and to raise the issue of their mistreatment. The 1983 Emigration Act was the crystallisation of this evolving stance.

However, it wasn’t just a change in policy. Tiwary claimed that the community itself stepped up and demanded that their rights be protected.

Also read: India’s wide diaspora can help country achieve $10-trillion economy, says finance secretary

Modi’s diaspora outreach

According to Tiwary, the term ‘diaspora’ was first used by the Rajiv Gandhi government in Parliament. By the 1990s, the term was in vogue.

Special departments and committees were instituted to safeguard the interests of the diaspora community. In 2004, the Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs was founded. The diaspora was now being recognised as an unequivocally Indian entity, vital to the enhancement of the country’s image at home and abroad.

But biases persist. “The government is more focused and inclined towards the successful diaspora and not those who are considered part of the liability diaspora,” said Tiwary.

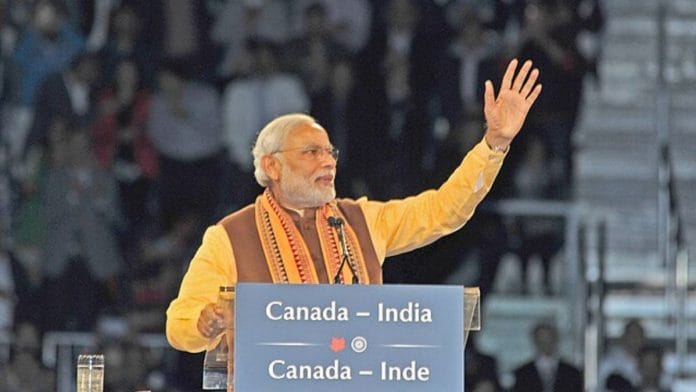

The UPA government used the diaspora pragmatically, she stated. Then an emphatic wave came when Narendra Modi was elected into power. As many as 50,000 people attended the ‘Howdy Modi’ event held in Texas, US, in September 2019. Not only was it a reflection of the bonhomie between Modi and then-US President Donald Trump, but it was a rallying cry of support from Indian-Americans.

“It [diaspora outreach] is a Modi phenomenon. Wherever Modi goes, he reaches out. This kind of policy was never there earlier. It’s both de-territorialisation and hypernationalism,” Tiwary said.

Also read: Indian agriculture is ‘a walled-off garden stuck in the 60s’. Private investment is the answer

Nuances in definition

The diaspora is no monolith. There are nuances in the definition—migrant, expat, NRI, all carrying different connotations. Tiwary stated that ‘migrant’ is often used as an all-encompassing term, but a migrant isn’t necessarily a member of a diaspora.

If an individual has severed ties to their home nation and no longer associates with their social and cultural markers, they aren’t considered a part of the diaspora.

However, following the telecommunication revolution in the late 20th century, severing ties was no longer an easy option. The rise of hyperconnectivity led to a generation suspended in liminality—physically in a foreign nation but rooted at home.

The lecture ended with a question-and-answer session. A Delhi University professor of political science criticised Jawaharlal Nehru’s policy of “active dissociation” from the diaspora. He was quickly shut down by another audience member—Professor Rajiv Malhotra, a senior fellow at the Nehru Memorial Library.

“It wasn’t a Nehru policy. It was more paternalistic guidance. If you want to be successful you have to be part of that particular society,” he said. The context in which the world operated back then was dramatically different.

What was then touched upon but not delved into was a question that has seeped into popular discourse: What is a nation-state supposed to do when its global community harbours sentiments that don’t align with its own?

Tiwary’s answer was singular and precise: bilateral dialogue.

“That’s the only logical conclusion,” she said. She was swiftly countered by multiple voices in the audience—apparently, dialogue doesn’t always suffice.

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)