New Delhi: In his two years of visiting museums across London and beyond, journalist and author Shyam Bhatia has become convinced that the British Museum is nothing less than a disgraceful, brazen display of ancient looted objects from India. He even proposed banning officials from the institute from visiting museums in India.

Officials at the museum look at Indians with contempt.

“I’d rather spend an afternoon in Gaza protecting my life than spend an afternoon in the museum”, Bhatia said in his lecture, ‘Stolen Gods: The Afterlife of Empire in British Museum’.

Art curators, appreciators, filmmakers, museum directors and artists had gathered for the lecture on 13 August in the Seminar Room of Kamladevi Complex, India International Centre.

Global experts and retired curators estimate that the India collection in the British Museum is worth at least £10 billion, Bhatia said.

He claimed that even if a part of the total value is returned to India as a reparative investment, it would fund the construction of around 28,000 new schools, 2,000 hospitals, and tens of thousands of kilometres of rural roads, creating over 25 lakh jobs.

Museums are about power

Research for an upcoming book took Bhatia across British museums to find out the scale of the objects looted from India.

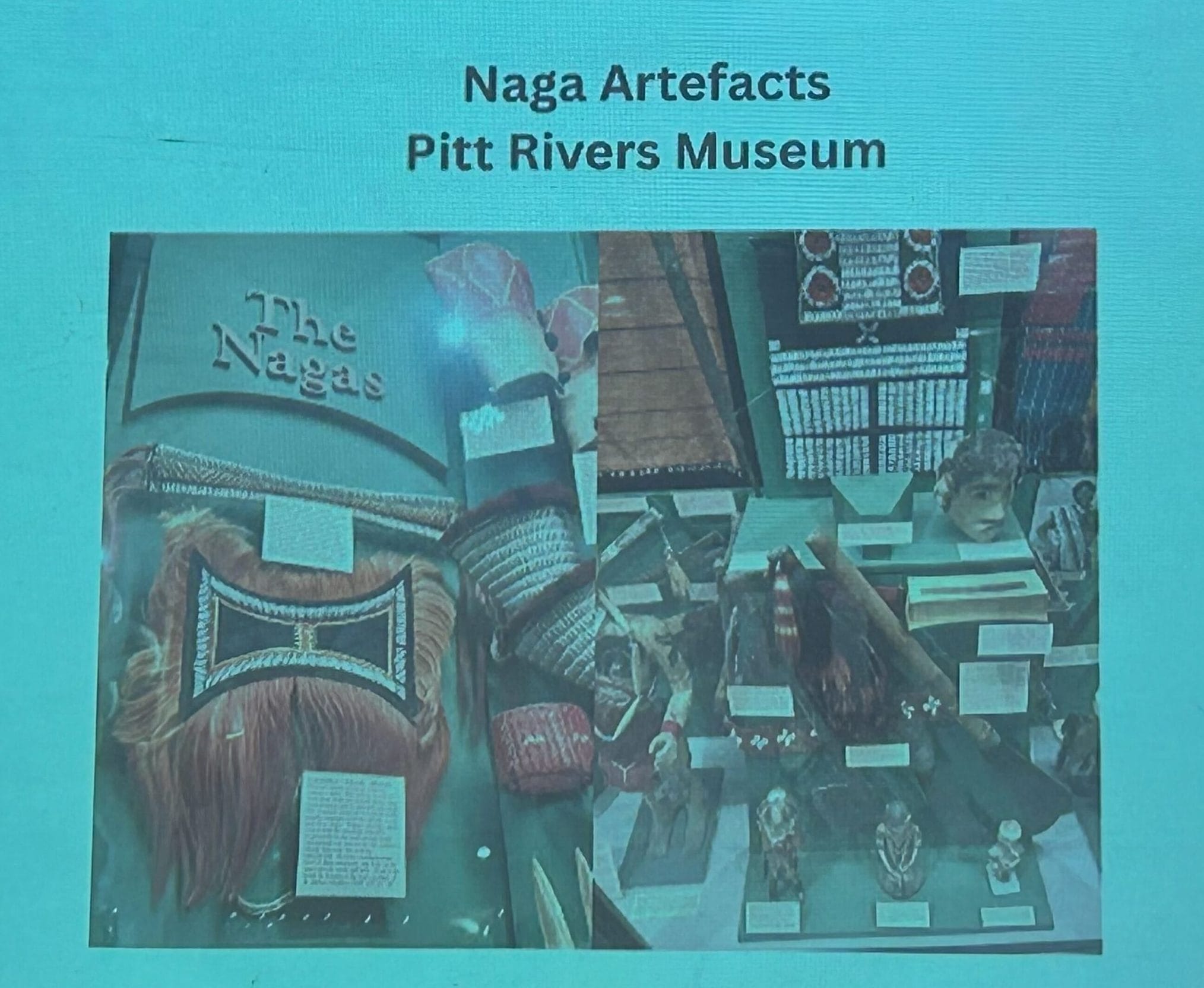

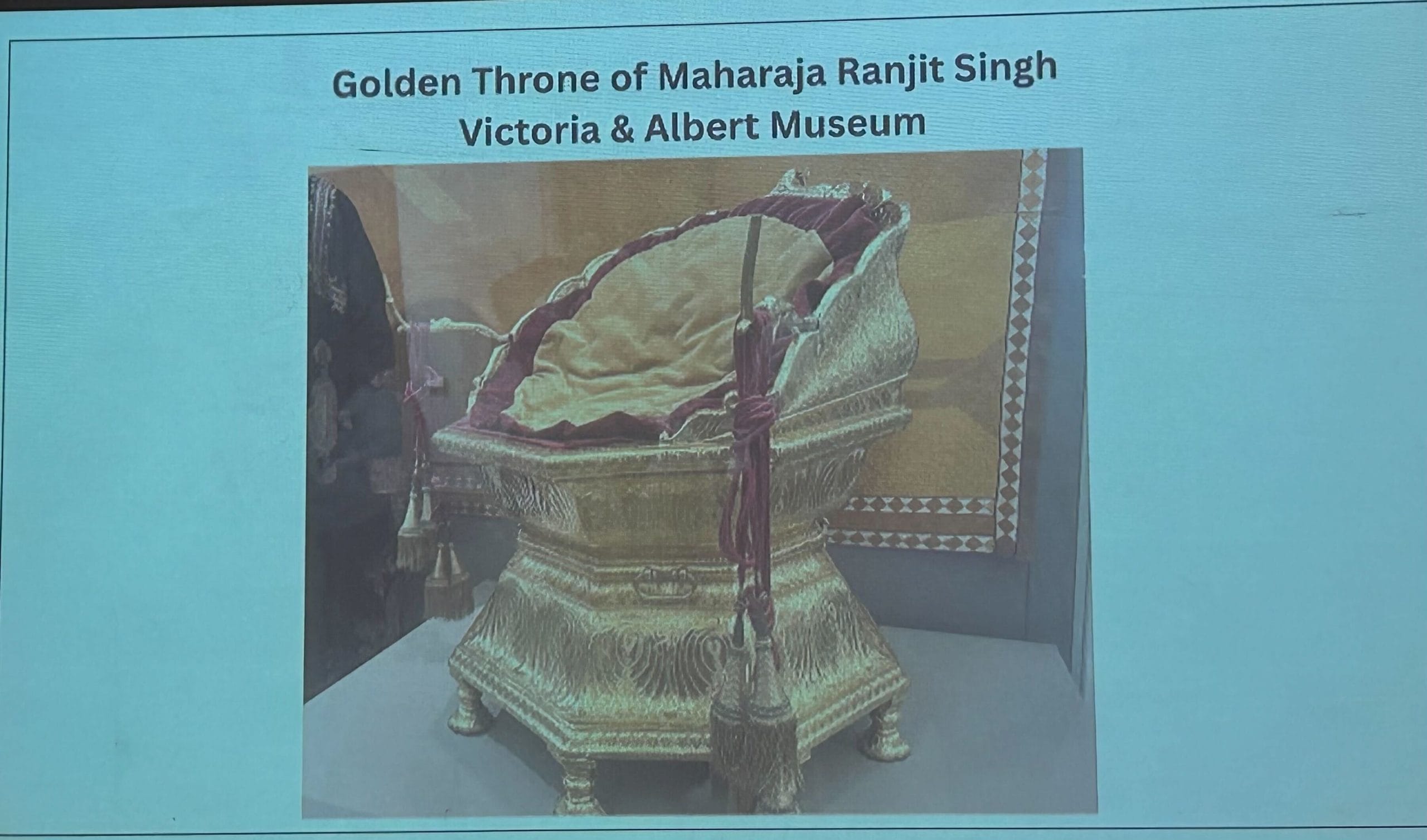

During his stay in London, Bhatia visited institutions like the British Museum, Victoria and Album Museum, and Pitt Rivers Museum. He uncovered several paintings and artefacts that are part of Indian history from different time periods, brazenly exhibited, from Amaravati sculptures to Tipu Sultan’s throne to the Chola bronzes. He said the institutions have turned “gods into trophies”.

The audiences were surprised as Bhatia attracted their attention to the screen, displaying the rarest of rare items stolen from India.

One of the slides showed the golden throne of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, the seat of the Lion of Punjab, who defied both the Mughals and the British. The throne is now displayed hours away from London in the Victoria and Albert Museum. It lies as an antique object, merely seen as a masterpiece of craftsmanship.

All these artefacts now cater to nothing more than decorative curiosities—edited wallpaper for the British aristocracy.

“The V&A [Victoria and Albert Museum]’s response to these histories remains conflicted”, said Bhatia. “When I spoke to the director, Tristram Hunt, he acknowledged the moral dilemma.”

In an interview given to the London Sunday Times, Hunt spoke about the need for an amendment in museum laws. He argued that the publicly funded museum trustees should have the right to make ethical decisions about whether art, artefacts, and paintings looted under duress or in the aftermath of military plunder should be returned.

Bhatia quoted from Hunt’s interview, discussing Tipu’s Tiger, which was looted in 1799 from the sultan’s summer palace. An almost life-size automaton in the form of a mechanical tiger mauling a European soldier, it was created for Tipu Sultan. A famous artefact among the museum goers, the Tiger is a vivid “embodiment of colonial conquest turned into imperial spectacle”.

In his lecture, Bhatia also drew attention to the Royal Collection. The photo on the screen changed to the Windsor Badshahnama, a group of works compiled into an official history of the reign of Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan I. Today, it’s a holding with the royal family. It was gifted to King George III in 1799 alongside dozens of other Mughal and Rajput treasures. The Royal Collection treasury, controlled by King Charles III, also has ceremonial armour, jewel swords, and engraved muskets from princely states like Hyderabad, Mysore, and Punjab.

“When we speak of museums, we are speaking of power, of narratives curated not just through display but through silence, of absences made to appear normal, of effort rebranded as preservation. There is also a psychological wound here. For many in India, the experience of visiting these museums abroad is disorientating,” said Bhatia.

Also read: Harappans were the first to use gold coins, not Kushanas

Ban British Museum officials

Bhatia said that British Museum officials should be banned from visiting museums in India. The officials from these museums who participate in so-called joint exhibitions go back to England without guilt and gloat about India being welcoming and Indian authorities being okay with them keeping looted objects.

“We are legitimising the continued ownership of stolen objects. Do not use India as a way to legitimise your plunder,” Bhatia said to British officials. “The British Museum’s problems are not only historical, they are contemporary, systemic, and ongoing.“

(Edited by Prasanna Bachchhav)