New Delhi: Writer Amitava Kumar’s The Green Book is, as its subtitle suggests, An Observer’s Notebook. But it’s also a plea for people of all ages to keep diaries; to write and write.

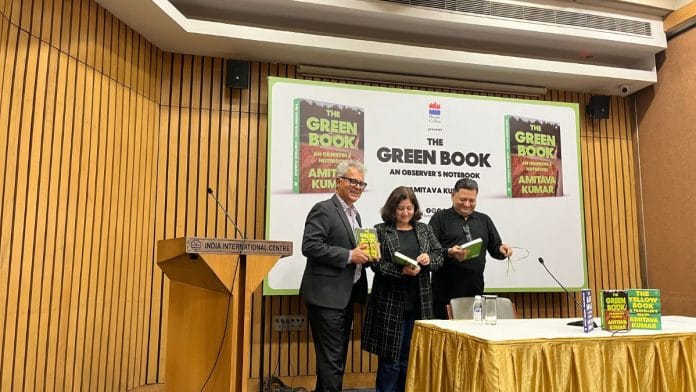

At the book’s launch event, held at Delhi’s India International Centre on 9 January, Kumar, who is also a professor of English at Vassar College, reminded his audience of the abundance of riches found in writers’ notebooks, and presumably—in their own. Published by Harper Collins India, The Green Book is a bit of a motley affair; both peppered and punctuated with sketches and photographs by the author. Some serve to intensify, to heighten the words on the page. But others simply exist.

“Writing badly is easy. You should part the curtain and write what you see outside,” said an emphatic Kumar. “Or at least write that you are not writing.”

At this point, from the inside of his jacket, Kumar whipped out a pocket notebook and began reading aloud. He had just met a friend whose father passed away. Each morning, their father would cinch in their curtains so they’d be able to sleep longer. As he was performing this daily task, he collapsed.

“Do coma patients feel pain?”—was what the friend had googled while in the hospital. Since the answer was yes, they decided to pull the plug. Through his potentially humdrum note-taking, Kumar stitched together an entire story.

“This is the real thing. The real thing is everything that’s on the page,” said Kumar, referring to his stubborn refusal to separate the real from the written.

Also read: ‘Mrs G was victim of communalism’ Shiva Naipaul wrote in his personal diary after Indira’s death

Tone of a first draft

One of Kumar’s preoccupations has been with unearthing the skeletal frames behind the work of famous journalists and authors—Shiva Naipaul, Jack Kerouac, Penelope Fitzgerald, John Berger.

Naipaul’s notes, which are mentioned in The Green Book, inlude his thoughts, observations on a challenging, nerve-wracking assignment: The 1984 anti-sikh riots, right after the assassination of Indira Gandhi.

“Delhi in the dawn, smelling of smoke, hazy on the road in from the airport. On a roundabout, a burnt-down bus, the smoking remains of a lorry.” reads the entry. Naipaul also describes Delhi as a sad, stunned city.

What ultimately makes it into the newspaper piece is a more precise, polished rendering. “The still smouldering wreck of an overturned lorry was abandoned on a grassy roundabout” is its new avatar.

According to Kumar, the entries also have little taste of anxiety, an uncertainty as to whether Naipaul was equipped to condense a society and polity as vast as India. Kumar assessed his judgements as both arrogant and uncertain.

“As often as diaries reveal secrets, they receive silences,” said Kumar, speaking about their dual, complex nature.

The Green Book, just like its predecessors, The Yellow Book and The Blue Book, provides the reader with a glacial, open-armed viewing experience of at least one part of Kumar’s inner life. This is deliberate, and something he wants to accommodate in his novels as well.

“You want that tone of a first draft,” he said. “Even a novel should have the freshness and immediacy of blood on the bandage.”

He’s not writing at leisure. There’s sweat dripping from his nose onto his notebook. That’s the kind of urgency he’s writing with, which is then distilled into a shared intimacy between reader and writer.

An audience member used the word “perplexed” to explain what reading the brief of the book was like. The mixing of forms, the lack of linearity, the transitions in space and time. Kumar appeared to be amused—feigning offense.

Another audience member, an aspiring writer, and self-confessed fan asked Kumar whether he felt nervous about publishing, about letting his books out. He responded with an anecdote from when he was in college, when he was desperate to get a room at the Delhi University hostel. It consumed him, filled him with dread. Coming from a village in Bihar, it was everything.

This was hard; writing and publishing on the other hand—comes with a different purpose.

“There are so many more urgent and pressing things that make you feel worthless. Writing is liberating.”

(Edited by Theres Sudeep)