Mumbai: Actor-director Amol Palekar calls himself a relic of the “dinosaur era” for handwriting a 450-page Marathi memoir during the pandemic. But the results are anything but outdated—a book filled not just with personal stories but also QR codes to unlock archival images, vintage photographs, and unseen works.

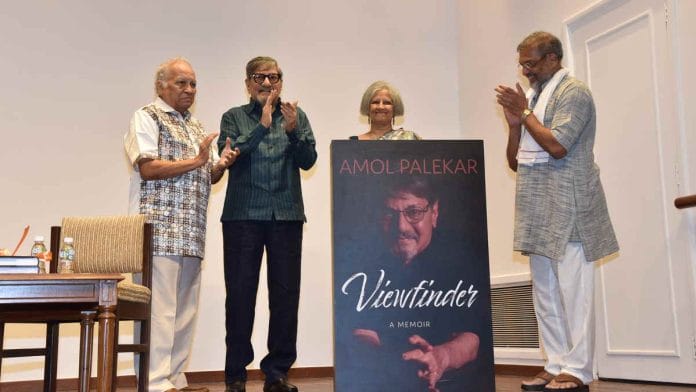

Last Saturday, on the eve of his 80th birthday, Palekar launched the memoir—Viewfinder in English and Aiwaz in Marathi—at the Hall of Culture in Nehru Centre, Worli. The event was attended by close friends and contemporaries, including Bollywood veterans Govind Nihalani and Nana Patekar. Through their speeches and a Q&A session moderated by journalist Sathya Saran, the evening offered glimpses into Palekar’s personality on and off screen—far beyond the Meek Young Man he was often typecast as in 1970s films like Chhoti Si Baat and Rajnigandha.

For Palekar, the memoir was a labour of love that he shared with his wife, Sandhya Gokhale. Over the past year, she transformed his scribbled notes into a finished book, adding what Palekar described to ThePrint as its “flavour and fragrance”.

Gokhale has also upheld a tradition of celebrating her husband’s milestone birthdays in meaningful ways. In 2020, for instance, she adapted a Danish film into Kusur, a play that brought Palekar back to the stage after 25 years.

Published in English by Westland Books and in Marathi by Madhushree Publications, the memoir will hit stores on 9 December. It captures the many lives Palekar has lived—as a painter, theatre artist, actor, writer, and director.

“I’ve been able to do all the things I wanted on my terms without being on one single beaten path,” he told ThePrint, adding that he has fared well in maintaining distance and objectivity while looking at his own life.

The launch was attended by around 100 people, including fans and fellow artistes, eager to connect with Palekar. When the floor opened for questions, several took the mike just to express how much they missed seeing him on screen and to encourage him to create more content.

With his characteristic humour, Palekar joked: “I will make it if you produce it.”

Also Read: ‘Chhoti Si Baat’ to ‘Piya Ka Ghar’, heritage walk takes you through Basu Chatterjee’s Bombay

‘Portraying black vs white is very easy’

During the Q&A, Palekar tipped his hat to the man who changed his life—director Satyadev Dubey, who cast him in the 1971 Marathi film Shantata! Court Chalu Aahe. Known for his temper and for once even throwing a chair at an actor, Dubey was blunt about why he hired Palekar—it wasn’t for his talent, but because he was free.

“Dubey was the starting point of everything that I am today,” Palekar said. “And somewhere, my calming influence changed him.”

From this unassuming start, Palekar went on to become the quintessential everyman of Indian cinema. In his Hindi film debut, Rajnigandha, he played the talkative, forgetful Sanjay, whose apologies came with white rajnigandha flowers. Then came Arun in Chhoti Si Baat, a shy daydreamer with a colourful fantasy life.

While speaking to The Print,Palekar pointed out that his characters never said, “I love you” but always found other ways to express their affection.

With films like Golmaal (which earned him the Filmfare Best Actor award in 1980) and Naram Garam, Palekar became synonymous understated, relatable comedy.

But he soon grew restless.

“Once I knew that what I have done is good and people have loved it, I lost interest in playing the same kind of roles. I wanted to try out different things, even at the risk of failing,” said Palekar, who found playing the protagonist or hero extremely one-dimensional.

Breaking away from his boy-next-door image, he explored darker roles, like the homicidal villain in Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s Khamosh (1986).

During the script reading, Palekar suggested that the antagonist should remain calm, not scream and shout.

“Ever seen a cat prey on a mouse? It doesn’t kill at one go. It plays with the mouse, catching it, letting it go, catching it again. Vinod loved this idea!” reminisced Palekar.

He credited much of his artistic versatility to his training as an art student at JJ School of Arts.

“Portraying black versus white is very easy. The real challenge lies in finding the gradations of grey. I applied this concept as a visual artist, actor, director, and everything,” he said.

Also Read: Mohinder Amarnath plays bold in his ‘Fearless’ memoir. Picks Imran Khan over Gavaskar

‘I don’t believe in spontaneity’

Amol Palekar had his own exacting standards when he turned director with Thodasa Roomani Ho Jaayen in 1990.

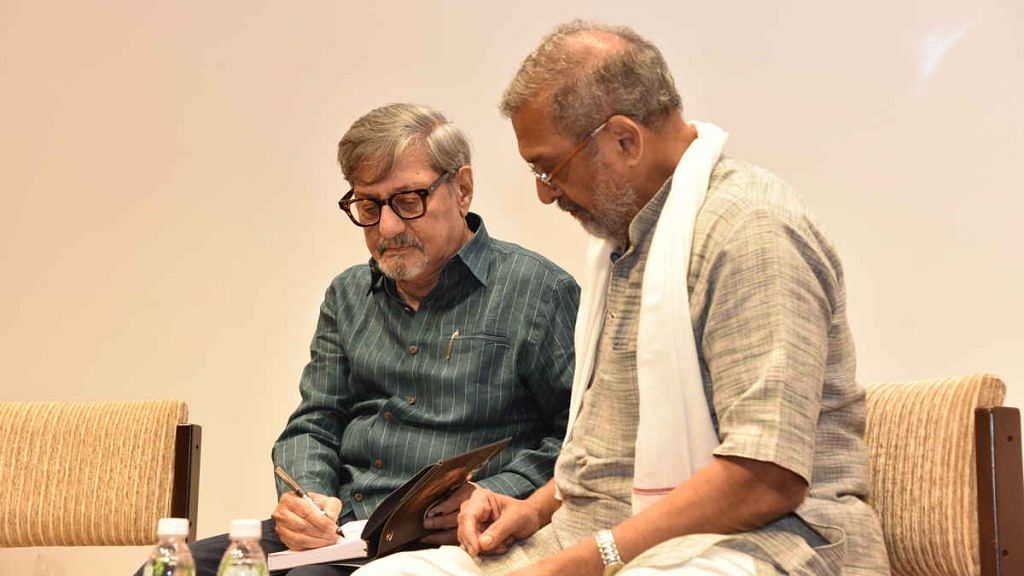

On stage at the launch, veteran actor Nana Patekar shared how Palekar’s sharp eye for detail kept even seasoned actors on their toes. Despite Patekar’s acclaimed performance in Parinda, Palekar wasn’t sure he was right for the role. Patekar then offered to rehearse for a week to prove himself. By the end of the week, the character of Natarwal had fully taken shape, and Palekar cast him without hesitation.

Palekar himself described his artistic process as anything but impulsive.

“I don’t believe in spontaneity. I never do anything without proper rehearsal or without thinking things through. Everyone must know precisely what is to be done,” he said.

Palekar, who recently appeared in the Netflix series Farzi (2023), also spoke about the breadth of Indian cinema, which he avidly follows through OTT platforms.

“All regional cinema that happens in our country is equally important…What happens in Malayalam cinema today is as important or probably a little more important than most of the trash in Bollywood,” he said.

But the event wasn’t just about Palekar’s professional side. It also revealed the warmth and constancy of his personal relationships.

Ali Haider, his childhood friend from Shivaji Park, stressed that Palekar never let fame go to his head.

“He’s very human. That’s one quality people leave behind when they become successful or have a little more money. Amol hasn’t changed one bit,” he said. “My mother asked him to take care of me when we were seven, and he has lived up to it.”

This thoughtful, methodical nature also shaped Viewfinder, which Palekar crafted not just as a memoir but as an “homage to the stalwarts” who influenced his career.

“The book traces the journey of Indian cinema and theatre—which parallelly traces my own evolution as I become more and more mature, or immature,” he smiled. “A viewfinder is a small telescopic instrument used to set a frame of a movie camera. I have given a look at my own self through my own viewfinder.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)