New Delhi: India’s first Dalit MacArthur fellow, Shailaja Paik doesn’t shy away from critiquing BR Ambedkar’s methods. She argues that his ideas on upliftment divided Dalit women into two camps.

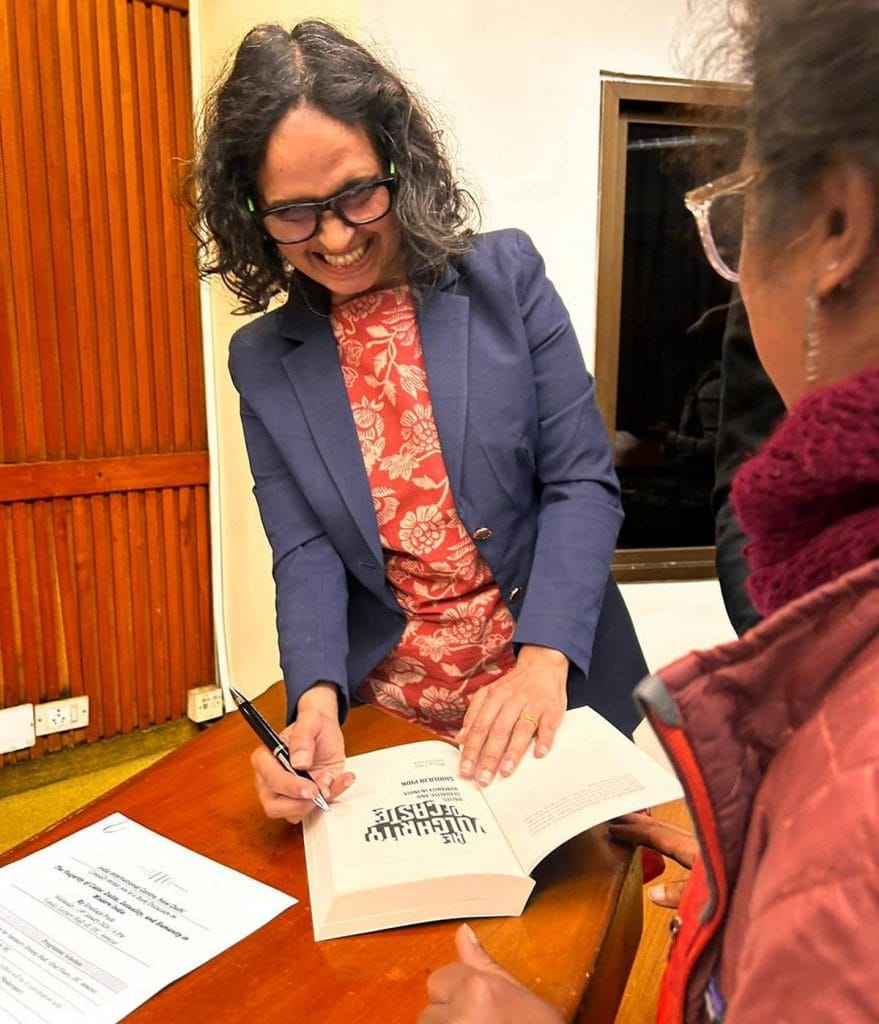

“I have critiqued him in terms of how he created two kinds of women: a moral woman, as opposed to an immoral woman,” Paik told ThePrint during a whirlwind visit from the US to Delhi this month. At venues such as IIT and the India International Centre, she discussed her acclaimed book, The Vulgarity of Caste: Dalits, Sexuality and Humanity in Modern India, to standing-room-only audiences.

Paik in her books has argued that Ambedkar challenged and exposed the vulgarity of caste that oppressed Dalit women. At the same time, he also asked Dalit women to participate in political activities and work towards community uplift.

Now a US citizen, Paik teaches history at the University of Cincinnati and was awarded the $800,000 MacArthur Fellowship, known as the ‘genius grant’, in 2024 to further her research. Though she has several new projects underway, including The Cambridge Companion to Dr B R Ambedkar, her Delhi stop focused on The Vulgarity of Caste (2022), which won the American Historical Association’s John F Richards Prize, among other awards.

While Paik extends Ambedkar’s theories on caste and endogamy, she takes a sharp-eyed view of his gender politics, specifically in the context of sexualised Dalit women theatrical performers in Maharashtra.

“The so-called prostitute, the Tamasha woman, the Jogini, were looked upon as dishonourable because they were threatening Dalit radicalism,” said Paik, weighing each word carefully. “On the other hand, a Dalit woman toiling away in factories becomes the respectable Dalit woman.”

In 1927, Ambedkar rejected a donation from Patthe Bapurao, the partner of Tamasha performer Pavalabai Hivargaokarin, saying the movement did not want money earned from the exploitation of Mahar and Mang women. In her book, Paik also writes of how Ambedkarite activists turned folk theatre into a “sanitised” form called Jalsa by stripping away its “ashlil” (obscene) themes to make the movement look more respectable to the outside world. This new version effectively erased women like Pavalabai.

The unintended consequence of such a stance, according to Paik, was a “cleansing” of women whose survival depended on the very art forms the movement sought to disown.

However, she cautioned against reading this as “patriarchal”, instead calling it a response to complex pressures.

“Dalits as a community were depicted as docile, animal-like, ignorant,” she added. “What Ambedkar was trying to do was erase these depictions. This move was also important to regain Dalit manuski and to uplift the community in its own eyes and in the eyes of society. Calling it a patriarchal move is very narrow and limiting.”

Also Read: ‘Dalit devadasis lowest on social ladder’— Karnataka tackles twin stigma of caste, sex work

Dalit scholar in Trump 2.0

Students and academics jostled for space at a basement hall in IIC for Paik’s book reading and discussion. Before moving into passages dense with nuance, she paused and stressed words such as Tamasha, manuski, and exploitation. She made it look like these pauses were intentional. They signalled her insistence that the audience not merely listen, but connect with the lived realities embedded in the stories she encountered during her fieldwork.

Paik resists being boxed in as only a MacArthur Fellow in the United States. She started out from a single room in Pune’s Yerawada, received a Ford Foundation grant for her PhD at the University of Warwick, and has spent more than two decades working at the intersections of caste and gender.

And yet she is not immune to the prevailing discrimination in the US. Caste has global implications, which Paik realised when she was repeatedly asked what her surname was by Indians she’d encounter in the country.

“I faced some overt and more covert discrimination. People would want to constantly know my surname because Paik is not a common surname found among Marathis,” she said.

There are now also the pressures of being an academic in the Trump era, particularly in fields dismissed as ‘woke’ by the political right.

“A lot of changes have taken place at the institutional level, but I have been able to manage and shape the work that I want to do. That said, the use of certain words is not allowed, so we are just thinking about how we can continue to do the work,” she said, referring to the expanding list of words flagged or scrubbed from government websites under the Trump administration, including ‘woman’, ‘gender’, ‘identity’, and ‘discrimination’.

Despite this, Paik said, scholars are finding ways to navigate these constraints. She draws parallels between Black and Dalit feminism, while acknowledging differences in location, culture, and context.

“It’s important for us to understand the parallels of oppression, the ways women from these communities have resisted, how they have challenged both public patriarchy and private patriarchy, and how they have been resilient,” she said, adding that she is also co-editing a volume titled Caste, Race, and Indigeneity in and beyond South Asia.

When it comes to India, Paik said, Dalit issues are still “undermined” in the media, and at best “sprinkled” sparsely in the overall news coverage. The larger question, she added, is who gets to make decisions in newsrooms.

“It also depends on who is in the office — and who allows it,” Paik said.

Also Read: Dalit dating in India is a choice between dignity and loneliness

Social location and skin

After the reading, the floor opened for questions. They came thick and fast, on caste, performance, sexuality. Paik noted each question carefully on a sheet of paper with a pencil before responding in short, clipped sentences.

Divig Kare, a student from Ambedkar University, asked about the absence of Dalits in public spaces and whether anything had changed over time.

On this, Paik spoke of how Dalits found a voice in art forms such as Jalsa.

“Dalits, through the medium of Jalsa—the song, the drama—showed how they experienced public space and how they demanded their place in it,” she said.

Another audience member, Shantya, wanted to know if erotica had always been part of Tamasha performances.

Paik had a nuanced response. In forms such as Tamasha and Lavani, she said, women’s bodies and work were consumed, yet they were excluded from the public sphere. That contradiction continued even in Marathi cinema.

Films such as Pinjara (1972) and Natarang (2009) brought Tamasha performers in to train actors, but “paid no attention to the caste, the social location and politics of the actors.”

On erotica in Tamasha, Paik urged for a new focus. “What is happening here, and whose body is on display?” she asked. The “social location” of that body, she said, could not be separated from the performance.

Tamasha, however, is a mode of survival for families and can also be a lucrative business.

“The system, Tamasha, has exploited Dalit women, hence they are exploiting Tamasha. It is a double whammy,” she told ThePrint.

But Paik added Tamasha should not be equated with the agency of modern women expressing their sexuality on platforms such as social media.

“This was caste slavery,” she said. “Tamasha women performers came from families bound for generations to caste-based servitude, where women and their families were coerced through violence, arson, and forced displacement.”

She also pointed to a “gendered division” within Dalit Tamasha troupes.

“Dalit men often depended on women’s labour for survival while simultaneously oppressing them. Women sang, danced, and wrote lyrics, while men controlled the logistics,” she said.

Another form of oppression is also a near-universal one in India: the obsession with light skin. Pavalabai, for one, was extolled by writers for skin that was so fair that when she ate paan, her throat turned red.

“She would be given more value compared to a dark-skinned woman,” Paik said. “The artists are always putting makeup and a lot of powder and so on to look fairer.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)