New Delhi: Every morning, Abid Qureshi scrolls through Facebook and flips through the Assignment Abroad Times, a biweekly paper for overseas jobs. Last month, one ad caught his eye: construction workers wanted in Moscow. After 12 years on Saudi sites and several more doing poorly paid odd jobs back home, Russia looked like a step up.

“The money would be better than in the Gulf,” said Qureshi, a resident of Rajasthan’s Churu. “I’m 49, and Europe and Russia are more relaxed about age. They don’t close the door,” he said.

The agency behind the ad accepted his CV and offered a 20-day training course to be conducted by Russian companies in November. The fee: Rs 2 lakh. Qureshi borrowed from friends to make the payment. It’s worth it to him with the promised Rs 1 lakh monthly wage in Moscow. In Saudi Arabia, where he last worked, his wage was around Rs 40,000 per month; the job ended when the company shut down.

Workers like Qureshi have their life stitched together between visas, contracts, and wire transfers. But now the working-class migration dream is travelling far beyond the traditional Gulf routes. With countries such as Japan, Greece, and Russia struggling with demographic change and low working-age population, Indian workers are starting to fill the blue-collar labour gap in new corners of the world. Government policies and a growing network of recruiters are greasing the wheels of this migration.

“Israel, Poland, Greece, Japan, and now even Russia—that’s where the demand is,” said Shrikant Ingle, founder of BCM Group, a Pune-based licensed overseas recruitment agency with staffing networks across Latvia, Croatia, and Romania. “Before the pandemic, we mostly placed IT professionals abroad. But afterwards, the global labour market flipped. Blue-collar demand exploded, and tech hiring slowed down. We had to adapt.”

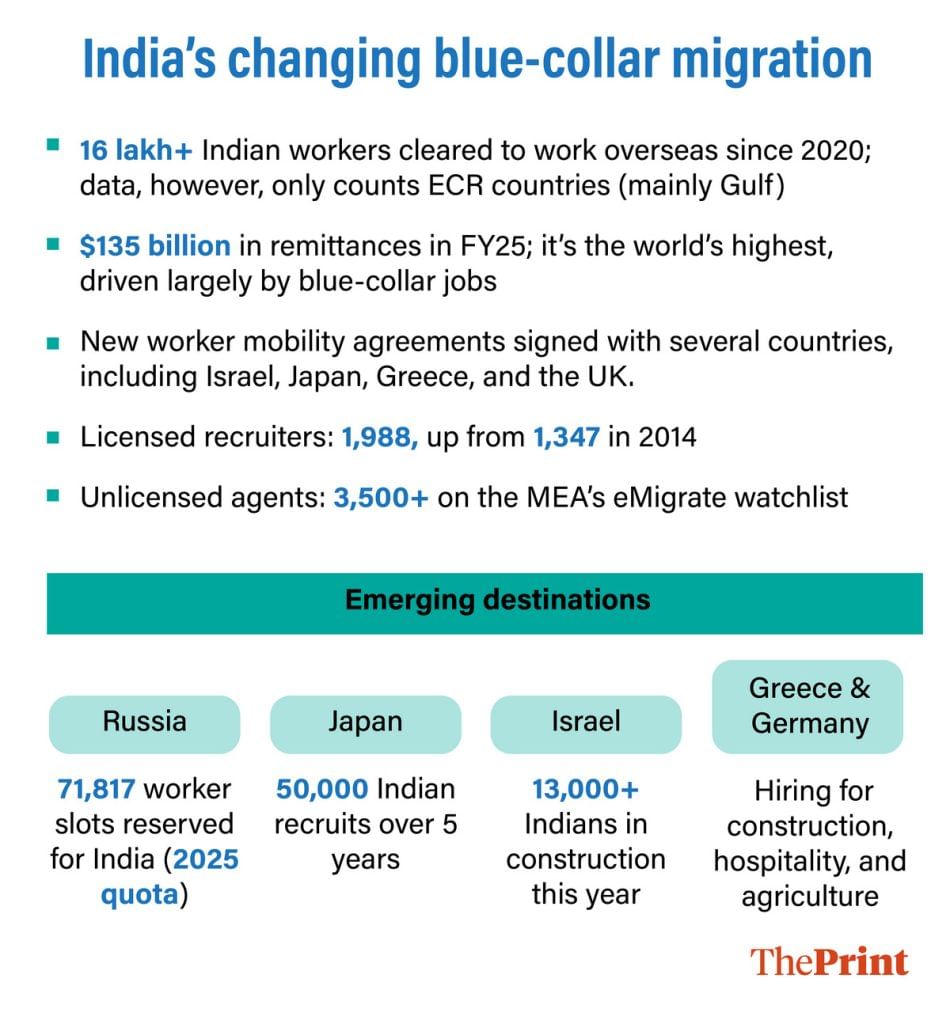

The government has kept up. In May, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar said countries such as Italy, Spain, Austria, and Greece have “shown the appetite to tap into the human resource pool in India”. Last year, the MEA signed migration and mobility partnership agreements with Israel, Taiwan, Malaysia, Denmark, and the UK, adding to earlier arrangements with Germany, Italy, France, and Austria. The ministry also noted in a July 2025 report that “significant progress has been achieved in negotiations” with Croatia, Finland, Greece, Guyana, Russia, and Switzerland. Earlier this year, a human resource exchange deal was signed with Japan as well.

When the interviewer asked me my name and purpose of visit, I answered in English. I paused many times, but I felt confident. I came out trembling, but soon after, I had a visa in hand

-Mohammad Shahban, Greece-bound tile mason

Japan’s 2025 plan aims to bring in 50,000 skilled Indians over five years through formal training and placement programmes. Greece is working with Indian authorities and licensed agencies to recruit workers for construction, agriculture, and hospitality. Russia has reserved 71,817 slots for Indian workers out of its 2,34,900 foreign-worker quota for 2025, even as its labour ministry denies any “mass recruitment.” Under a bilateral framework, 6,730 Indians joined Israel’s construction sector in July, apart from over 6,400 through private channels. Germany, which has a shortfall of around 200,000 construction workers yearly, has also shown growing interest in skilled Indian labour.

MEA data shows that between January 2020 and June 2025, over 16 lakh Indians in construction and other labour-intensive jobs were cleared to work abroad. The count, however, covers only ECR (Emigration Check Required) countries, mainly in the Gulf, where government clearance is needed and migration is officially recorded. Workers heading to newer destinations such as Russia, Israel, and Greece travel on non-ECR, or ECRN, passports and don’t show up in government data.

In FY25, India received a record $135 billion in remittances, with Mexico ($68 billion) and China ($48 billion) at a distant second and third. Blue-collar work is a major driver. Indian workers are building highways, airports, factories, hotels, homes, and commercial complexes abroad — and keeping their villages running with the money they send home.

But competition is intense. Workers from Pakistan, Bangladesh, the Philippines, China, and Southeast Asian countries are also in the reckoning.

“Workers from places like Cambodia and China are about 20 per cent more expensive but often more skilled and disciplined,” said Mohammad Alam Mirza, founder of Tarmac Technical Manpower Services, a labour supplier.

There is now, however, a growing machinery of organised agencies helping Indian workers like Abid Qureshi upgrade their skills.

“Russians will train us themselves in installing aluminium windows and glass work. There will be new construction materials, but the tools are the same and the job isn’t hard,” he said.

Qureshi’s CV is green and white, made a decade ago when he learnt Microsoft Word. His name sits in bold at the top, followed by the title “warehouse worker”. Below are the languages he knows, several learnt not in a classroom but a construction site— English, Hindi, Urdu, and Arabic. A passport scan and a photocopy of his Class 12 certificate complete the package.

In his “About” section, he has typed: “Self-motivated, ambitious, and hardworking, with zeal for professional progress and career advancement through determination.”

Also Read: ‘We build India, who will build Bihar?’—Chhath train is a migrant story of despair

Going from Gonda to Greece

A grey four-storey office building sits unassumingly in a cramped lane in southwest Delhi’s Palam, a few metres from the airport. Inside, it carries the weight of thousands of Indian dreams. This is Dynamic Staffing Services (DSS), a recruitment company sending electricians, machine operators, warehouse workers, forklift operators, automotive mechanics, and even butchers and bakers to countries such as Greece, Israel, and Romania.

The reception has posters of smiling men and women in hard hats or medical gear, all with a tagline in common: “Are you looking for a job overseas?”

The room smells of caffeine, fresh stationery, and sweat. The atmosphere is tense.

Around 15 men sit clutching old rice sacks stuffed with the documents of their lives — Aadhaar cards, laminated school certificates, CVs, passports. Most aspirants come here from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and Rajasthan — small towns where joblessness weighs heavy and every rupee matters. Their shirts are ironed but their chappals and shoes are dusty and worn. Several wear a gamcha around their neck.

The agency offers various courses, ranging from technical skill upgradation to “cultural adaptation”.

In a language training room beyond the reception, a whiteboard lists three terms:

Too heavy — poy vyari

Soft — malakós

Hard — sklirá

Seated at wooden desks, eleven men mutter the Greek words under their breath again and again. Language training is conducted batch-wise depending on the destination country. Sometimes employers pay for these sessions; in other cases, workers cover the cost themselves.

In the second row sits 35-year-old Mohammad Shahban from Gonda, 150 km from Lucknow.

When his turn comes, he stands and announces his name: “Me léne Mohammad Shahban.” He is careful, deliberate, and proud. The class smiles. He laughs too, a little surprised at himself. Now he speaks Greek.

For more than a decade, Shahban worked as a tile mason, mostly on false ceilings. Then a phone call from a friend set him on a new path. Through DSS, he’s spent four months preparing for a stint abroad. He’s taken medical tests, interviews, skill exams, and is learning Greek and English. Now it’s just days to his departure.

Our goal is for workers to arrive skilled, digitally aware, and ready to work in a new environment from day one

Prashansa, English-language trainer at DSS

“I got a B grade (in my assessment),” he grinned. “They told me I’m ready to go.”

Every morning, he returns to class, repeating Greek phrases, safety instructions, and greetings.

“It’s difficult,” he admitted, “but I’m learning.”

For his embassy interview, Shahban bought a new shirt and trousers for Rs 450 at his village market. He polished his four-year-old shoes till they shined, said a short prayer, and walked in.

“When the interviewer asked me my name and purpose of visit, I answered in English,” he said. “I paused many times, but I felt confident. I came out trembling, but soon after, I had a visa in hand.”

How are workers trained?

Behind every Indian worker who leaves home for a construction site in Tel Aviv or a hotel in Athens stands an elaborate machinery of recruitment and training.

At Dynamic Staffing Services, as in most other similar companies, the process unfolds over several months.

Once a foreign client puts forward a request for workers — often 200 to 300 at a time — the agency’s sourcing team spreads word through firms, agents, WhatsApp groups, and pamphlets pasted at labour chowks and tea stalls in small towns. Applications are logged into a database, and suitable candidates are called for tests and interviews.

The screening process can be intricate. DSS is among the few Indian agencies that run their own trade centres to assess skills such as welding, tiling, and electrical wiring under the watchful eyes of supervisors. Masons might build small walls, electricians wire panels, welders join metal sheets. Each is graded A, B, or C to determine readiness for the job.

Once candidates are finalised, the clients raise visa requests.

At that point, the staffing agency takes over the training process. It is divided into three modules: language lessons, skill upgradation, and digital literacy.

Now job opportunities have increased in sectors like civil engineering, building, roads, infrastructure, and manufacturing. But if the number of jobs has increased, so has the number of workers willing and available to work

-Varun Khosla, managing director, Dynamic Staffing Services

For skill training, the agency polishes each candidate’s capabilities for their trade, whether mason, electrician, or carpenter. The sessions cover safety and discipline, as well as work ethics and etiquette. Digital training focuses on tools such as ChatGPT, Google Maps, Translate, and Gemini AI, along with other smartphone apps that can be used for essential tasks.

The DSS Palam branch has 13 trainers — native speakers of the target language or Indians who have spent several years working in that country.

“Our goal is for workers to arrive skilled, digitally aware, and ready to work in a new environment from day one,” said English-language trainer Prashansa.

Preparing for takeoff

At the Palam centre, as the workers slowly start settling into their chairs, Prashansa starts her morning English class not with grammar drills but a question: “Did you listen to the cricket commentary last night?”

For the former IELTS trainer with years of experience coaching students for global tests, this is not polite conversation but teaching strategy. She asks students to listen to YouTube videos and podcasts even if they can’t understand every word.

“Your ears learn first,” she tells them. Cricket commentary is her secret weapon. “Workers from across South Asian countries love sports, so I use that. When they hear English spoken fast and with energy, it builds rhythm and confidence.”

Her lessons stick to the essentials: how to ask for a tool, give directions, or talk to a supervisor. Someone mispronounces “screwdriver,” and the whole class laughs.

As workers prepare to leave for new countries, trainers introduce them to the local culture, climate, and social norms. Motivational talks and orientation sessions help reduce the culture shock.

Parallelly, the agency handles the paper labyrinth: medical tests, police verification, passport checks, and visa documentation. DSS liaises with embassies, schedules interviews, and coordinates tickets.

I can earn in two months here [in Israel] what I made in a year back home. If I work five more years, my daughter can study in an English-medium school, maybe become an IAS officer

-Govind Swami , window-fitter in Tel Aviv

For agencies, it’s a brisk juggling of logistics, business, and human management. And keeping pace with a changing hiring landscape.

“Previously, companies like Archirodon or Hyundai would directly come to India for hiring,” said DSS managing director Varun Khosla. “Now job opportunities have increased in sectors like civil engineering, building, roads, infrastructure, and manufacturing. But if the number of jobs has increased, so has the number of workers willing and available to work.”

The agency was started 47 years ago by Khosla’s father in Mumbai. Today, it has 23 offices in 16 countries and has deployed more than six lakh workers overseas.

Every year, around 16,000 to 18,000 people go abroad through DSS. While the Middle East still takes the lion’s share, according to Khosla, they now supply workers to over 30 countries.

He speaks proudly about his father, the late Major (Retd) SP Khosla, who worked with the government during the drafting of the Emigration Act of 1983, meant to safeguard Indians going abroad to work. Representing recruitment agents nationwide, SP Khosla helped build a framework that looked at worker welfare and made the industry more transparent and legitimate.

“It’s a business shaped as much by policies as by the global demand for affordable labour,” Khosla added.

Which jobs are real?

Over the past few months, Instagram and Facebook feeds have been flooded with flashy job ads in red and blue fonts, screaming: “Urgent! Required for Russia!” They promise five-year visas, direct selection, free accommodation and food, and salaries that sound too good to be true. There are callouts for railway track fitters, masons, factory helpers. All freshers are welcome.

The images on the posters are usually AI-generated white workers on construction sites. The comments sections are awash with anxious queries: “Will it be safe?”, “What language to learn?”, “What is the process like?”, “How to apply?”

Many of these posts, however, list no company name. When ThePrint dialled some of the provided numbers, no one picked up or called back. In one Instagram ad for warehouse workers and delivery drivers in Russia, a commenter warned: “Bhai tumhara paisa fass jayega yeh log chor hai… mai proof deta hu”—Brother, your money will get stuck, these people are thieves, I have proof.”

Behind the bright banners lies a murkier reality. BCM Group co-founder Srikant Ingle said many such social media ads are fraudulent, targeting small-town workers.

“They often extract Rs 10-15 lakh and disappear later,” he added.

The MEA’s eMigrate portal lists over 3,500 unlicensed recruitment agents and companies, with their addresses, states, and number of pending grievances.

Earlier, when something went wrong, there was nobody to file a complaint to. Now, if there is a query, there is an office, a receipt, and a phone number to call

– Sorabh, construction worker bound for Sri Lanka

Part of the problem is that only workers in the ECR system are properly tracked, with about 4.8 million registrations covering profiles such as carpenters, electricians, cooks, and construction labourers. The rest of India’s semi-skilled export workforce moves through unrecorded channels, where scams lurk.

At the DSS recruitment office, many of the men waiting to be called in share stories about freelance agents who vanished after collecting fees, or sent workers on tourist visas, making their lives more difficult.

India has also seen cases of men lured abroad on the pretext of blue-collar jobs and ending up drafted into the Russian army amid the war with Ukraine. In September, MEA spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal warned of the “risks and dangers” of such recruitment and said Delhi had asked Moscow to release all Indians serving there.

But there is also a growing number of legitimate, registered recruiting agencies. In 2014, the MEA listed 1,347; in 2024, these had risen to 1,988. These outfits are more transparent, coordinate with foreign clients, and offer support to workers.

“Earlier, when something went wrong, there was nobody to file a complaint to. Now, if there is a query, there is an office, a receipt, and a phone number to call,” said 34-year-old Sorabh from Gopalganj, who previously worked in Dubai and Qatar. He is now leaving for a piping job in Sri Lanka through DSS for a salary of $540 (around Rs 47,000).

BCM’s Ingle speaks passionately about being a counterpoint to the disorganised underbelly of blue-collar recruitment.

“I stick to licenced processes, a CV, skill test, interview, visa, and no shortcuts,” he said. “Our people are hard-working, willing to learn. The world needs them, and they need to work. We just have to build the bridge properly. The fraud business needs to stop.”

Founded in 2009, the Pune-based company works across IT and non-IT sectors. One of its specialisations is placing welders, fitters, CNC operators, construction workers, and other blue-collar workers in companies across Russia, Romania, Hungary, Croatia, Serbia, and Slovakia.

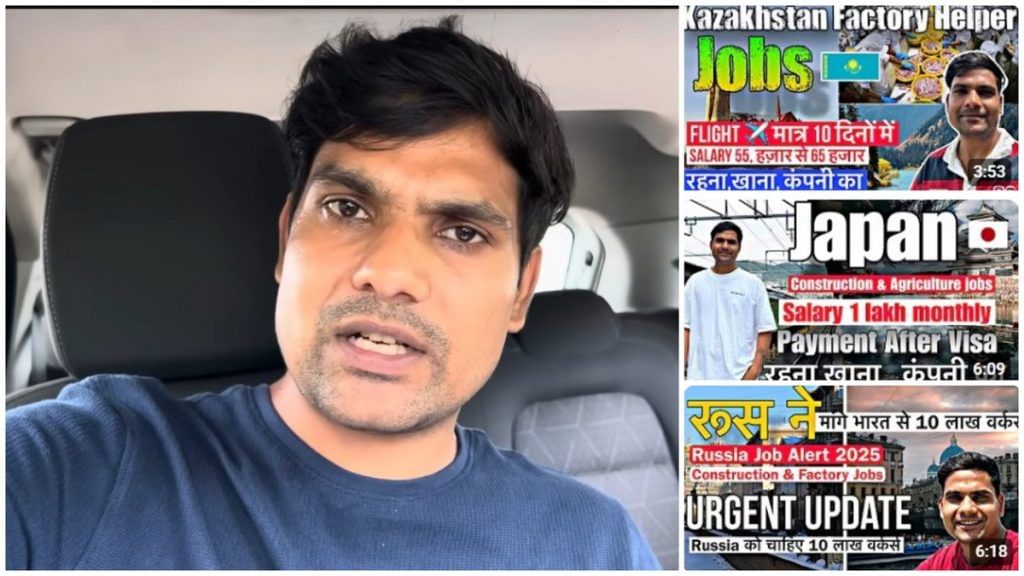

YouTube outreach

Outside the formal recruitment networks, a loose chain of freelancers and consultants operates across borders. One of them is Shahbaz Ahmed. From a single room in Bangkok, he runs a small operation as a migration consultant primarily for blue-collar jobseekers, guiding them to agents in Russia, the Gulf, and smaller European countries. He hasn’t dabbled in the US or Canada. He calls it a “whole different game”.

A former employee of a private firm in Oman, he spends much of the day going through CVs and says he is applying for a government manpower licence. He also runs a YouTube channel, ‘Shahbaz Wandurlust’ (sic), where he apprises his 1.4 lakh followers about job openings along with detailed advice on documents and processes.

“When a blue-collar worker looks for a job, the first place he goes to is YouTube,” he laughed. Even before the local agent.

People think they will earn one lakh a month in Europe. It is only possible when they are highly skilled

-Shahbaz Ahmed, migration consultant and influencer

Recent videos include one on packing jobs at a Russian food warehouse, openings for factory helpers in Kazakhstan, and supermarket positions in Malta. For the Russian food packing job, one hopeful commented: “Maine BSc food bhi ki hai.” In another video on a greenhouse job in Israel, Ahmed told viewers they could apply only if they had farming experience, claiming the salary was around Rs 3 lakh. People often ask him for his office address, but he tells them to WhatsApp him instead.

His phone buzzes. It’s someone enquiring about a food delivery executive job in Serbia.

“People think they will earn one lakh a month in Europe,” he scoffed. “It is only possible when they are highly skilled. I share whatever verified information I get about job openings, but I never promise anything I can’t deliver.”

The workers who reach out to him mostly come from rural or semi-urban backgrounds. Skill, he said, is the real dividing line.

“A mason, fabricator, or carpenter is a skilled worker. They earn more. Helpers make not so much,” he added.

From the workers themselves, there’s a fixation on salary alone, according to him: “They don’t ask about the working conditions, the contract, or the job. It doesn’t matter.”

Also Read: Labourers, masons, fitters going online for jobs. A LinkedIn for construction workers

Upward-mobility migration ladder

The first great wave of Indian working-class migration began in the 1980s and 1990s, when workers from Kerala filled construction sites across the Gulf, building towers in Dubai and Riyadh. Over time, men from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and Rajasthan joined them, turning the Gulf into a lifeline for India’s working class.

But the tide is turning as the Gulf economy slows and new destinations open their doors. Where migration once moved in waves, it now follows smaller currents, driven by changing markets and visa rules. The migration route now looks like an upward-mobility ladder, starting with the Middle East and climbing toward Western countries as the top rung.

“Wherever the government allows, people will go,” said Mohammad Alam Mirza of Tarmac Technical Manpower Services. “They just want a better salary, a better life.”

Russia has become one of the most promising destinations in this new phase. The country faces a projected shortfall of 3.1 million workers by 2030 and is looking beyond the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) for manpower. India has become one of its fastest-growing sources of non-CIS labour, according to an October 2025 paper by Gateway House: Indian Council on Global Relations.

“The labour movement in the India-Russia corridor is a new element in the bilateral. It is already visible in the Delhi-Moscow flights. The usual students and tourists now share the cabin with welders, salon workers, and builders,” it read.

But there are several hurdles, ranging from the weather to issues caused by the Russia-Ukraine war.

“In Russia, the weather is brutal, and the language is a real barrier,” said Ingle. “VPNs are blocked, so it’s hard to access job portals or talk to companies.”

Varun Khosla of Dynamic Staffing Services said his firm is waiting for sanctions to ease so that hiring can expand. “We want to lead the way and provide high-quality candidates for Russia,” he said.

Both countries, meanwhile, are taking policy steps to smoothen recruitment. In July, Russia passed a law exempting quota-based migrant workers from mandatory Russian-language exams and simplifying work-permit procedures.

India, for its part, is planning to fast-track the opening of new consulates in Kazan and Yekaterinburg. And worker mobility— especially in IT, construction, and engineering— was among the key issues discussed during External Affairs Minister Jaishankar’s visit to Moscow in August.

Greece too is recruiting Indian workers for agriculture, manufacturing, and construction — fields that local workers are reluctant to join. For Indian workers, though, any place in Europe is a step up.

Every night, Raza Abbas, a steel fixer from Kolkata, reads about Greece on his Redmi smartphone. The 36-year-old is preparing to leave for Athens and has been learning about the city’s history and how the Olympics started there. He’ll earn about Rs 1 lakh a month, up from Rs 20,000 back in India.

In Israel, conflict has become a factor in recruiting more Indians — some 80,000 Palestinian construction workers were banned from the country after the October 2023 Hamas attack.

“I can earn in two months here what I made in a year back home,” said 37-year-old Govind Swami over a video call from his dormitory in central Tel Aviv. His work entails fixing aluminium window frames in a concrete building — measuring, cutting, and adjusting them all day. “If I work five more years, my daughter can study in an English-medium school, maybe become an IAS officer.”

Swami spent years building walls in the Gulf and in Tiruppur, Tamil Nadu. He can read blueprints, handle new materials, and adapt to any site. Those skills have carried him from one country to another.

But he knows he has to keep moving up. His next targets are Russia, Poland, Romania.

“Migrant workers like us have fought hot sun, sand, and now cement. And then we look at colder countries.”

(Edited by Asavari Singh)