Where there is no free will

Rajmohan Gandhi | Research professor at Centre for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign

The Indian Express

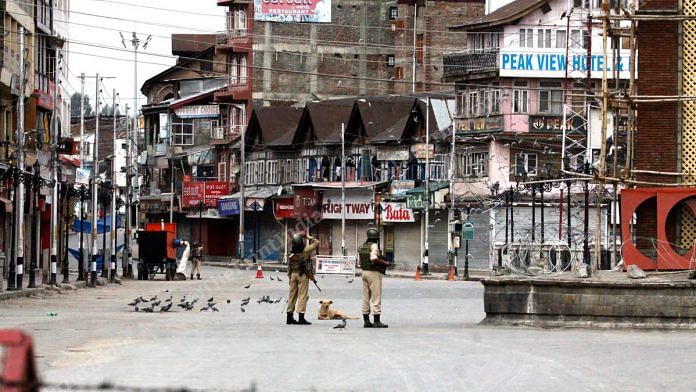

Gandhi writes that amidst celebration over the revocation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir, there is a need to “reflect on the word consent”. Even if hypothetically the move turns out to be greatly beneficial for J&K in terms of peace, development, gender equality and economic opportunities, Kashimiris will still be angry because their consent was not obtained.

Kashmiris may never give up their anger. Kashmir’s “long insurgency” has made it a region hard to rule and also made it unpopular in the rest of the country. Most people today celebrate what has happened in Kashmir as they feel “the time has come to hurt them”, and they can assert their control over the Valley.

Kashmir’s environmental ecology is also at stake, and to protect this, “a barrier much stronger than Article 370” was needed.

An intervention that leads to more questions

Priyanjali Mehta | Independent researcher and author of ‘India’s Nuclear Debate: Exceptionalism and the Bomb’

The Hindu

Mehta writes the statement issued by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh on Twitter on former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s death anniversary was like “policy-making by tweet”. Stating that India’s commitment in the future to ‘No First Use (NFU) of nuclear weapons’ policy would from now on “depend on circumstances”, Singh’s announcement marked a shift in India’s nuclear stance without any formal prior “deliberation or consultation”.

India’s commitment to NFU, first officially discussed and debated 20 years ago in BJP’s draft of India’s ‘Nuclear Doctrine’, has always emphasised the “commitment to restraint”. This position has been good for India as a strategy — be it while dealing with Pakistan or in gaining support from the international community.

NFU’s revocation does not necessarily mean there will be no restraint, but could mean “ambiguity”, potentially leading to miscalculations like in the 1999 Kargil War. Those who prefer a more “muscular nuclear policy” are not in favour of the NFU.

As doubts add up about India’s economy, the future of J&K, India’s federal system, the question of what has caused this revised nuclear doctrine is also yet to be answered, writes Mehta.

100 years of Afghanistan

Vivek Katju | Former Secretary, MEA

The Times of India

Katju writes about Afghanistan’s tumultuous history — beginning with its ‘independence’ from British forces in May 1919 after the Treaty of Rawalpindi. It was an “absolute monarchy” under the Barakzai Pashtun family in 1919 until Zahir Shah converted it into an institutional monarchy in 1964.

He was soon overthrown in a coup staged by his brother Daud Khan, who dismantled the monarchy and appointed himself as the President.

Zahir Shah’s rule had signified “internal calm, infrastructural development” and a “neutral” foreign policy. The Daud Khan coup destroyed this, paving way for radical communists who killed him and caused widespread violence. As chaos ensued, the Soviet Union decided to move its troops into Afghanistan in December 1979 to maintain control. The “violent and tragic” decades since then have seen different political phases from communism to three years of “Afghan nationalist-authoritarianism”, three years of “mujahideen confusion”, Taliban rule, to a democratic Islamic republic.

As the Taliban gains momentum, the future of Afghanistan is uncertain, but a “full-blown Emirate” is likely to call for resistance. Economic liberation depends on peace and stability, which is awaited as the US prepares to withdraw its troops while Pakistan “waits in the wings” to once again negotiate for the Durand Line to be the border.

Not a Bumpy Cycle Ride

Omkar Goswami | The writer is chairman, Corporate and Economic Research Group (CERG) Advisory

Economic Times

Goswami writes India’s present economic slowdown appears more like a structural problem and monetary policy alone can’t solve it. He writes India’s share of manufacturing to GDP has stagnated at 15 per cent for a long time and is less than countries like Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand and China. He also mentions that India’s gross fixed capital formation is low compared to other countries.

Among other problems, he highlights India’s low literacy rate, low share of women in the workforce and low exports. He recommends that India should create “sufficient liquidity with affordable credit flows to key sectors” — low-cost housing, roads and highways, rural infrastructure and textiles. He writes the first three have “high employment potential”, while the fourth “creates an essential product for the people”.

Improving supply of animal products

Neelkanth Mishra | The writer is co-head of Asia-Pacific Strategy and India Strategist for Credit Suisse

Business Standard

Mishra writes some provisional data from the 20th livestock census conducted last year is now available. He writes livestock now constitutes over a third of India’s agricultural output. He writes “growth in the number of animals for each of the livestock categories was significantly lower than the output growth reported by the Central Statistical Organisation (CSO)”.

He suggests that this discrepancy is not due to any inaccurate assessments, but likely has a “more credible and meaningfully more positive explanation”. He mentions, for instance, that while India’s total bovine population is unchanged, the number of males has decreased and the number of females has gone up. This implies “an improvement in efficiency and incomes when looked at on a ‘per person’ basis,” he writes.

He points out that there is another interesting trend as the livestock population of states like Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar and West Bengal has increased tremendously.

“Geographical diversification also provides some resilience to local supply disruptions that can emerge from disease or weather-related events,” he writes.

Appointing a chief of defence staff would just be the first step

Nitin Pai | Co-founder and director of The Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy

Mint

Pai writes that the appointment of a CDS would constitute one of the most important defence reforms in decades. He argues that the most important reason to appoint a CDS “is to separate management and command of the Armed Forces”. He suggests that since the CDS is likely to act as the principal military adviser to the government, the armed forces should be “operationally restructured into theatre commands — complete joint war-fighting formations — led by combatant commanders”.

He writes that conceptualising and implementing the theatre command reform will be one of the first major tasks of the new CDS. He also says the CDS needs to analyse how effectively the armed forces utilise resources allocated to them. For that, an economist should be appointed in the defence ministry, Pai recommends.