As India celebrates 75 years of Independence on 15 August, Bangladesh commemorates and mourns the death of its founding father, ‘Bangabandhu’ Sheikh Mujibur Rahman or Sheikh Mujib.

He was one of the most prominent politicians and champions of human rights and freedom during the nation’s fight for liberation against the atrocious rule of erstwhile West Pakistan. The first acting President of Bangladesh and later its Prime Minister, Mujib is remembered as the architect of independent Bangladesh.

His six-point movement, which demanded a separate currency, power of taxation, and a distinct militia, among others, is viewed as one of the first definitive moves for Bengali autonomy and rights in Pakistan.

“My father, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, had spent the most precious parts of his life in prison. As he got involved in various movements to wrest the rights of his people from those who had snatched them away from them, he had to endure solitary confinement again and again. But he would never compromise on his principles. He was not intimidated even by the hangman’s noose,” says Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina in the preface to her father’s book, The Unfinished Memoirs.

On 15 August 1975, Mujib, along with most members of his family, was assassinated by a group of Bangladesh Army personnel as part of a military coup. Only two members of his family, his eldest daughter Sheikh Hasina and her sister Sheikh Rehana, survived because they were not at the presidential residence. His death altered the course of Bangladesh’s history. The military took over the reins of the country, bringing democracy to a halt for about 15 years.

Also read:

A force to reckon with

Born on 17 March 1920 in the Gopalganj district of Dhaka, Khoka, as Mujib’s parents lovingly called him, was the third child in a Bengali Muslim family. A born leader, he organised a student protest in his school against an inept principal and demanded his removal.

Even before entering politics, Mujib was a fierce opponent of British rule in India and was heavily influenced by the ideas of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. He studied political science at Kolkata’s Maulana Azad College and even attempted to pursue law at the University of Dhaka post-Partition. However, he was expelled before he could complete the course for ‘inciting fourth class employees’ in their protests against the university.

Joining the All India Muslim Students’ Federation in 1940 marked the beginning of Mujib’s political career. Under the Bengal Muslim League, Mujib grew to become one of the most significant political leaders in his region.

Also read: Bengali poet Jibanananda Das took over Tagore’s legacy by not trying ‘too hard’

The beginning of Bangladesh

Perhaps one of the first prominent events in Mujib’s life as a student leader was the Bengali language movement. After the Muslim League’s declaration to adopt Urdu as Pakistan’s official language, Mujib organised a mass movement opposing its policies. Playing a key role in the strike on 11 March 1948 and opposing the imposition of Urdu on the Bengali population led to his eventual arrest. However, Mujib and fellow youth leaders were released following student pressure. Mujib continued to organise numerous strikes opposing the autocratic rule of West Pakistan, despite numerous jail stints throughout his life.

On 23 February 1969, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was given the title ‘Bangabandhu’ (Friend of Bengal) by the Chhatra Sangram Parishad as gratitude for spending most of his youth in prison for a free Bangladesh.

In 1963, Mujib rose to lead the Awami League and under his influence, the party soon won a massive majority in the Pakistan general elections on 7 December 1970. While Mujib won a landslide victory, he was unable to form a government due to opposition from Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, head of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), who threatened to boycott the National Assembly if Mujib was made prime minister. This led to a political impasse, with then president Yahya Khan delaying commencing the Assembly.

Also read: Dilip Kumar Roy, the Cambridge-educated elite who added melody to India’s freedom movement

Words of freedom

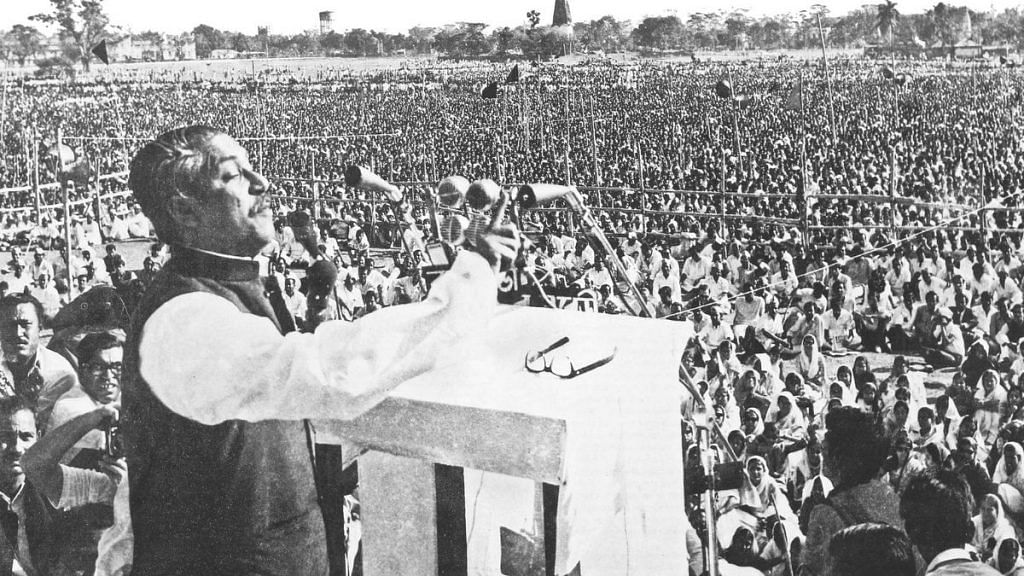

Mujib’s most historic speech in his political career was on 7 March 1971, when he called for Bangladesh’s independence and launched a civil disobedience movement against the repressive and violent regime of Yahya Khan.

“He turned his guns on my helpless people, a people with no arms to defend themselves. These were the same arms that had been purchased with our own money to protect us from external enemies. But it is my own people who are being fired upon today,” said Mujib, while addressing the violence his people faced at the hands of the Pakistani army.

But the fire in him refused to die.“The Bengali people have learned how to die for a cause and you will not be able to bring them under your yoke of suppression,” declared Mujib.

Roughly three weeks after this historic speech the Bangladesh Liberation war began on 26 March 1971, which lasted for more than eight months and was filled with bloodshed. Soon, Mujib was arrested without charges and taken to West Pakistan, where he remained imprisoned until 8 January 1972, when Bhutto was forced to release him under international pressure.

The transition to a new nation would be far from smooth—from confiscating ready cash to seizing private vehicles, West Pakistan had made sure to leave the fledgling economy in a deplorable state. But Mujib was determined to fulfil his goal of national reconstruction. He nationalised industries and helped Bangladesh join the United Nations and the Non-Aligned Movement. For years, Mujib travelled abroad, seeking aid and strengthening diplomatic ties with nations. But he wouldn’t live to see his efforts bear fruit.

(Edited by Zoya Bhatti)