In Calcutta, Swami Vivekananda used to go from place to place in search for “truth” asking lecturers a simple, yet daunting question, “Have you seen God?”

While most would be taken aback, one answered in affirmative, and it was the Hindu mystic Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, who not only left Vivekananda with an impression but put him on the path to see God too.

And thus began the journey of a young, spirited monk towards the life of being a disciple of Ramakrishna and the transformation into who the world today calls Swami Vivekananda.

A childhood marked with divinity

The Indian monk, who is credited with opening the gates of Hinduism and Hindu philosophy to the world, is now tokenistically remembered on 12 January — his birth date also known as National Youth Day. But little do we know what Vivekananda means to India’s youth today. Perhaps the best way to remember the great patriot is knowing him in detail and the timeless connection he built with future generations.

Young Vivekananda, born Narendranath Datta in a Bengali family, had a penchant for spiritualism right from an early age. Naren was believed to have had a firsthand encounter with divinity — at Vidyasagar College in Calcutta, he was meditating within closed doors with deep concentration when he lost track of time. What he saw next became a defining moment of his “dare-devil” life. From the southern wall of his room, a luminous figure stepped out and stood in front of him. He realised that the calm, head-shaved sannyasi with a kamandal (a wooden water bowl) in his hand was a visitor whom he would never meet again. The terrified boy fled the room as soon as wonder struck him. Recalling that memory, Vivekananda said, “It was the Lord Buddha whom I saw.”

A person’s thoughts and ideas are formed at an early age. And their personalities are a sum of all the life experiences, influences of literature, and family. When Vivekananda went to bed, a vision appeared that showed him as a person with endless wealth and property, perched at the top of the world. While convinced that he had the skills to achieve that ideal, young Naren renounced the material world at the following instant. Instead, he wrapped a loincloth around his waist and took to nocturnal rituals under the shade of trees. He felt that he could live the life of rishis and munis if he wanted.

Also read: Can’t expect world to eat greens, Vivekananda said meat was needed to make Indians mighty

Message to the West

Would embracing a life of humility mean choosing ‘insignificance’? On the contrary.

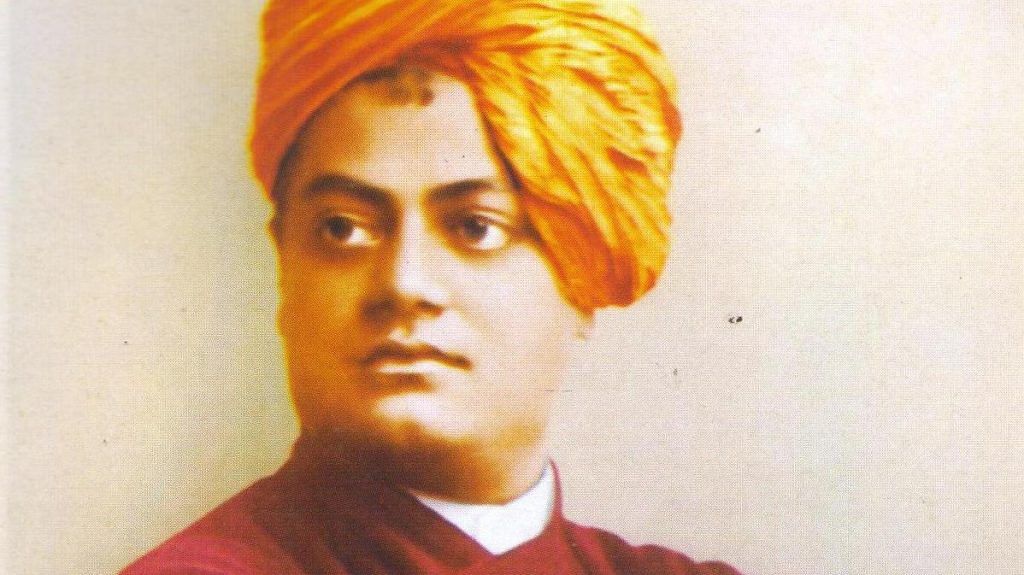

Vivekananda is one of the most prominent names to figure in the records of Parliament of the World’s Religions held in Chicago in 1893, where he introduced the audience to Hindu philosophy. Parliament President John Henry Barrows soon commented, “India, the mother of religions, was represented by the Orange-monk who exercised the most wonderful influence over his auditors.”

In the press, Vivekananda came to be known as the “cyclonic monk from India.”

Known for propounding the philosophy of Vedanta and Hinduism in the West, he spearheaded a distinctly Hindu education when the colonial world was still battling notions of cultural inferiority. To assume that the monk’s breadth of knowledge was limited to the philosophical would be a grave mistake. He mastered science and technology too — Vivekananda used Herbert Spencer’s mode of reasoning in his discussion of the doctrines of the Upanishads, and the philosophies of German thinkers Immanuel Kant and Arthur Schopenhauer were at his fingertips. John Stuart Mill and Auguste Comte were among his favourites, and William Wordsworth’s poetry drummed his poetic strings.

Perhaps there was an element of divinity associated with the Swami — notorious for his memory and sharp reading, he once quoted multiple pages verbatim from Charles Dickens’s Pickwick Papers and thereby earned the title of shrutidhara, one with prodigious memory.

Despite the expanse of his knowledge, he yearned sincerely for what was real and permanent — a sense of reconciliation with one’s spiritual self and God. On a trip to the US in 1894, Vivekananda stamped an image of himself by saying, “I have a message to the West as Buddha had a message to the East.” Nothing perhaps could capture him better than that.

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)