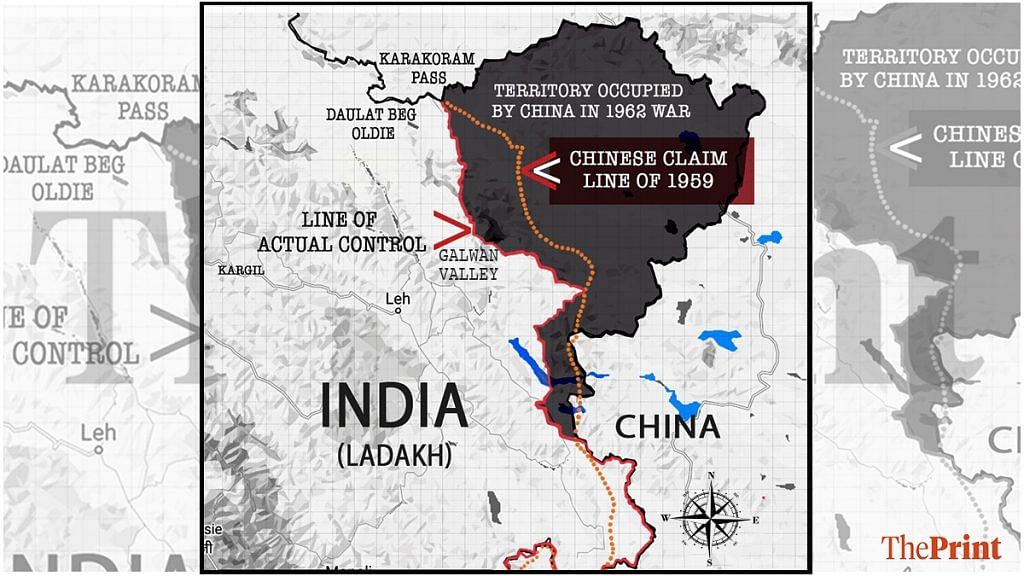

New Delhi: The Government of India Tuesday stated it does not recognise the “so-called unilaterally defined” 1959 Line of Actual Control, in response to a statement from Beijing that China follows the 1959 claim line as the LAC.

“India has never accepted the so-called unilaterally defined 1959 Line of Actual Control (LAC). This position has been consistent and well-known, including to the Chinese side,” said Anurag Srivastava, spokesperson for the Ministry of External Affairs.

India also asked China to “sincerely and faithfully” adhere to the border protocols signed between both sides from 1993 till 2012, and “refrain from advancing an untenable unilateral interpretation of the LAC”.

ThePrint explains what the 1959 claim line is, and why it’s a big deal.

Also read: Beijing is probably aiming for its LAC claim of 1959, China expert Yun Sun says

China’s 1959 LAC claim

China’s 1959 claim line can be traced back to the 1914 Simla Convention, which gave birth to the McMahon Line that separated Tibet from India.

Since signing the Simla Convention on 3 July 1914, the Chinese never raised any formal objection to the McMahon Line until January 1959, when Zhou Enlai, the first premier and head of government of the People’s Republic of China, wrote a letter to then-prime minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru.

China didn’t say a word even in 1950 when Nehru said, on the basis of the 1914 agreement, that “the McMahon Line is our boundary” and “the frontier from Ladakh to Nepal is defined chiefly by long usage and custom”.

However, in January 1959, Zhou’s letter contested the McMahon Line for the first time. He urged that it is imperative for the Chinese and Indian governments to have a “realistic attitude” towards the question of boundary settlement, calling the McMahon Line a “British policy of aggression” that cannot be considered “legal”.

Zhou also raised the issue of Aksai Chin for the first time with India, and thus started a series of diplomatic exchanges between Zhou and Nehru on the question of the LAC.

These diplomatic exchanges were based on a note that New Delhi had sent to Beijing in 1954, in which the Indian government “formally broached” the subject of China’s maps. India pointed out a map being used in Chinese magazines showed various areas that New Delhi regarded as its own territory, completely disregarding the Simla Convention and the McMahon Line, writes Neville Maxwell in his book India’s China War.

Until 1950, India was not open to negotiating the border, but as it increasingly saw the Chinese begin to follow a line that existed before the McMahon Line was formulated, New Delhi started to become alarmed.

“In the eastern sector, Chinese maps continued to ignore the McMahon Line and showed the Sino-Indian boundary along the foot of the hills… In the western sector, Chinese maps showed the boundary lying south-east from the Karakoram Pass to the Changchenmo River Valley,” Maxwell writes.

This was categorically rejected by Nehru as he realised Zhou was doing this under the direction of Chairman Mao Zedong as that was his “personal decision”, according to C.V. Ranganathan and Vinod C. Khanna in the book India and China — The Way Ahead.

Nehru was insistent because by January 1954, the North-East Frontier Tract became the North-East Frontier Agency (NEFA) and the “Indian control had finally been secured all the way up to the McMahon Line, four decades after it had been drawn at the historic meetings in Shimla”, Bertil Lintner writes in China’s India War: Collision Course on the Roof of The World.

Also read: PLA’s eye is on 1959 Claim Line. But Modi, Xi can get around it and make peace before winter

Zhou’s proposal

Nehru and Zhou kept exchanging letters, and in November 1959, the Chinese premier proposed that in order to preserve the status quo and maintain peace and tranquillity in the border areas, both Indian and Chinese troops should move back 20 kilometres from the “illegal” McMahon Line in the eastern sector, and from the “line up to which each side exercises actual control” in the western sector (Ladakh), Ranganathan and Khanna state.

Between January 1959 and Zhou’s proposal in November 1959, ties between India and China came under considerable strain with the outbreak of an uprising in Tibet’s capital Lhasa against the Chinese occupation, which led the Dalai Lama to seek shelter in India.

Maxwell notes that according to Zhou’s proposal, neither side would send armed patrols into the areas from which they withdraw; neither side will establish military posts in those areas; and only civil administrative personnel and unarmed police will be present.

But India rejected this proposal too. “In Indian perception, Zhou’s proposal would leave the Chinese deep inside Indian territory in the western sector, while Indian troops would have to withdraw further into India. In NEFA, such a withdrawal on the part of India would have imposed logistical difficulties for India,” according to Ranganathan and Khanna.

Also read: 1954 Panchsheel pact to Galwan Valley ‘violence’ — India-China relations in last 7 decades

The war

To discuss the issue more deeply, Nehru wrote to Zhou in February 1960, inviting him for a summit meeting to India. Opposition parties were up in arms and protested the visit, even as they cautioned Nehru to discuss border-related matters with Zhou.

The historic visit did take place, and in a joint communique issued on 25 April 1960, India and China stated “officials of the two governments should meet and examine, check and study all historical documents, records, accounts, maps and other material relevant to the boundary question”, according to a report of the Officials of the Governments of India and China on the boundary question.

Zhou also presented his own six points, a move intended to “somehow make India agree to their viewpoint”, says former Indian Army chief J.J. Singh in his book The McMahon Line.

Finally, with nothing working out by 1962, China began to prepare to strike India. Singh notes that at a key meeting in October 1962 at a place just outside Beijing, Chairman Mao was determined to “to go to war” with India, and is believed to have told his people “as long as the frontier troops fight well we will be in an advantageous position. It’s better to die standing, than to die kneeling”.

Thus, the war began with the Chinese invasion of Ladakh on 20 October 1962. The war went on for a month, and ended on 21 November with India’s defeat.

“1962 was a national failure of which every Indian is guilty. It was a failure in higher direction of war, a failure of the opposition, a failure of the general staff (myself included), it was a failure of responsible public opinion and the press. For the government of India, it was a Himalayan blunder at all levels,” states Brig. John Parashuram Dalvi, who commanded the brigade that was overrun by the Chinese and was himself taken prisoner, in a detailed account called Himalayan Blunder.

Also read: In mountains, China’s military prowess has a vertical limit. 1962 is a half truth