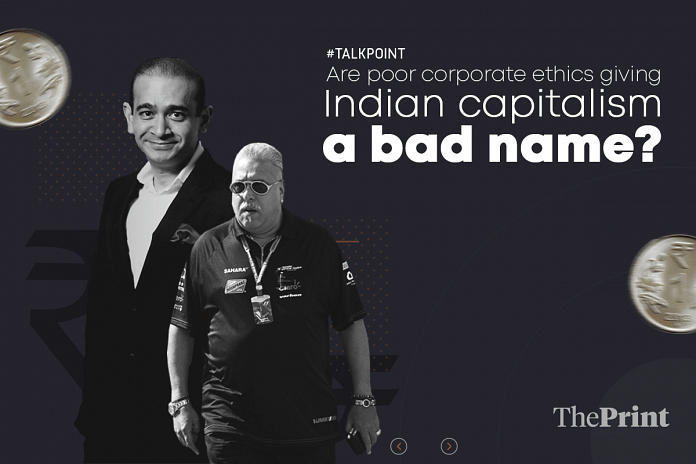

Celebrity jeweller Nirav Modi left India just days before the CBI started investigating him in connection with an alleged Rs. 11,400 crore fraud at the state-run Punjab National Bank. After Lalit Modi and Vijay Mallya, he is the third industrialist to have left India in the wake of investigations into business irregularities.

ThePrint asks: Are poor corporate ethics giving Indian capitalism a bad name?

Nirav Modi’s corruption and disappearance, after Vijay Mallya: Is India going through its own Gilded Age?

Ashutosh Varshney

Ashutosh Varshney

Director, Center for Contemporary South Asia, Watson Institute for Public and International Affairs, Brown University

Nirav Modi’s corruption and disappearance, coming upon Vijay Mallaya’s corruption and escape, raises a serious political economy issue: Is India going through its own Gilded Age?

Mark Twain, the literary giant of the last half of the 19th century America, coined the term “Gilded Age” to describe the industrial and financial corruption of the United States, as it rapidly grew from a predominantly agrarian society to an industrial one. At the end of the American Civil war in 1864, the US was 65-70 per cent rural. In the remaining three and a half decades of the century, its economy grew so rapidly – the highest economic growth rate recorded until then in history — that it became an urban-majority nation by 1900-1905. It also left Britain behind as the richest nation in the world.

Twain could feel corruption all around. We now have solid research to show that his feelings were right. Government-business corruption accompanied the rise of the US as an economic power. After 1900, President Theodore Roosevelt finally exercised government power to curb corruption.

Tales from South Korea and China in the late 20th and early 21st century speak of a similar phenomenon. Not known in India that much – despite the heavy presence of Samsung cell phones – South Korea today is a world-class industrial power. The corrupt business-government links undergirded South Korea’s rise as an economic powerhouse.

As for China, when I was last at Alibaba, owned by Jack Ma, as rich as Mukesh Ambani today, if not richer, executives of the company were complaining that Ma was spending more time pleasing politicians in Beijing, than at the firm headquarters in Hangzhou.

India’s choice is clear. Does it want to be a market-oriented or a business-oriented political economy? The former rewards innovation and drive; the latter privileges those who finance ruling political parties, their campaigns and politicians (though some such businesses may also add innovation in the bag).

The UPA government was accused of the latter, or more simply, of crony capitalism. The Modi government has to show that it is fundamentally different, not simply in rhetoric. Its closeness to business magnates, despite its claims of cleanliness, is becoming all too apparent.

American firms remain concerned about unscrupulous business activities in India.

Richard M. Rossow

Richard M. Rossow

Senior advisor and Wadhwani Chair in US-India Policy Studies, Center for Strategic & International Studies.

American firms remain concerned about unscrupulous business activities in India. There are three specific concerns, with some overlap between them—contract sanctity, the ability to “tilt” the playing field, and corruption. Despite progress, memories of early disasters are resilient.

In the decade after the 1991 reforms, most sectors required joint venture partners. Corruption was endemic, and some notable Indian joint venture partners harmed their foreign partners’ brands.

India has, on paper, solid laws regarding contract sanctity. But the process of legal remediation is long, as evidenced by India’s abysmal 164th place in the contracts ranking in the World Bank’s “Ease Of Doing Business” report. This was most noticeable during the first wave of American power sector investors in the 1990’s. They mistakenly believed their high electric power supply prices would be supported by a “sound” power purchase agreement.

The ability for Indian firms to use undue influence to “tilt” the playing field in a given sector can be more difficult to measure. One example would be the slow rebuilding of customs duty protections in sectors, or some of the mandatory “local preference” rules for government procurement in key sectors.

India is climbing Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. India ranked 79th out of 176 countries in the 2016 index. That is up four places from 2012, and ahead of Indonesia, Argentina, and Sri Lanka, among others. Judging by foreign investment and trade numbers, foreign firms are engaging India at a high level, likely a sign of both the market potential, and the strengthening of business fundamentals.

The Indian banking system, banking regulator and politician are getting a really bad name

Rama Bijapurkar

Rama Bijapurkar

Experienced Independent Director

I do not think all Indian corporates are being tarred with the same brush in people’s minds. There is greater awareness now of good and bad companies; hopefully making “reputation” a very important consideration when anyone is deciding to do business with an Indian company – be it small or large stock market investors, global business partners or dealers, customers, vendors etc.

However, what is getting a really bad name is the Indian banking system, the Indian banking regulator and the Indian politician, especially the ones in power when such scams happen. The banking regulator is seen as being quite ineffective on the big stuff, while being totally prescriptive on the small stuff – like the recent circular on how each branch of any bank must have a toilet, etc.

Banks are being perceived as having weak controls and supervision over their branches, making it easy for employees to defraud the system. Remember that this comes on the heels of Cobrapost and Vijay Mallya. Before that Deccan Herald and the ongoing NPA revelations. Politicians are seen to be directing banks to lend to the rich and powerful, and the banks, especially PSUs are seen to be agreeing without a fight.

This decline in perception of the integrity of the Indian banking system, and the ineffectiveness of its regulator, should cause a lot more worry. It should not be dismissed as “Indian businessmen are greedy and corrupt, the rest is fine”.

Crony socialism will continue as long as banks remain in the public sector

Gurcharan Das

Gurcharan Das

Author, Commentator, and Thought Leader

Although ethics do matter, I generally find that the blame lies in the incentive system. As Adam Smith pointed out many years ago, human self-interest drives markets. Self-interest is not greed or selfishness. Self-interest is behind normal human behaviour. For instance, if it rains, I take an umbrella. Nothing greedy or selfish about that. The theory is that the pursuit of self-interest in a competitive market leads generally to the public good.

The problem occurs when governments run businesses. The root of the problem in the Punjab National Bank case of fraud is, in great part, because it is a public sector bank. Why didn’t this happen in the case of HDFC Bank? When you have 70% of the banking assets of the country in the public sector, you also have a near-monopoly situation. The incentive system of the competitive market breaks down.

Hence, modern liberal states do not run businesses. In the private economy, it is someone’s money and they wouldn’t allow the money to be stolen. But in public sector banks, it is no one’s money. Hence, no sensible democratic country has a bulk of its banking assets in the public sector. And given our governance, especially the problem of judicial delay, crooks get away.

My essential point is, the government has lost an opportunity in this banking crisis to privatise some of the worst public sector banks. It was a golden opportunity. It should have bitten the bullet, as it has done in the case of Air India. Instead, our hard-earned taxes have gone into recapitalising the banks, and crony socialism will continue as long as banks remain in the public sector.

These incidents only contribute to the rapidly eroding belief in capitalism

Abhishek Krishnan

Abhishek Krishnan

Business Analyst at ThePrint

With public sector banks handling roughly 70 per cent of all gross advances made in 2017, the ‘isolated instance’ theory does not hold true, especially given the level of dependence of the economy on these institutions, and the size of bank frauds in the last couple of years. With the taxpayer’s money going down the drain in alleged scams, bad optics are inevitable, impacting both domestic and foreign investors’ confidence. This will manifest itself in two different ways.

In the long run, these incidents only contribute to the rapidly eroding ideological belief in capitalism, and the virtue of selfishness it has ushered in. Although capitalism hasn’t particularly been the bastion of economic equality, such incidents only amplify the ease with which a small section of the country can exploit the huge chasm in economic privilege. The kind of stress inflicted on public banks’ balance sheets will only stunt the sector’s ability to lend to smaller borrowers.

In the short/medium run though, these bank frauds send out a message, loud and clear – banking reforms are the need of the hour. PNB, being the second largest public-sector bank in terms of gross advances, itself contributes to roughly 8% of the total public sector Gross NPAs. This is the second time in the last five years that it has been involved in a major financial fraud.

Private sector NPAs, on the other hand, stand at a meagre 4 per cent of total gross advances. More government control over banks has only proven to be counter-productive, given the questionable risk mitigation techniques employed, coupled with a complete lack of law enforcement. The emergence of a new toxic concoction involving public sector inefficiency and muddled political-business networks will only spell doom, unless there is some incentive linked to these institutions.

Compiled by Talha Ashraf, Journalist at ThePrint.

Ownership structure cannot be the focal point in search of a panacea to the current systemic problems. Stamping out fraudulent activity and promoting competitiveness are different matters. History is replete with frauds leading to failure of Private sector banks or failure even with high degree of competition ( 1913-1918, 94 banks fails in India). The collapse of the global financial system and economic meltdown was triggered by mighty private banks; embers remain despite the actions of QE by various central banks and Govts. to stimulate economies. RBI hauling up big private names for not disclosing the entire extent of NPA and action initiated against fraudulent officials from private sector banks during demonetisation exercise are recent matters. On the specific issue of pnb’s bogus LoU issuance, it must be noted that the validity of LCs wrt gems and jewellery sector too seems to have not been questioned by the other participating banks including private once implies that mechanisms towards graded oversight in preventing/containing fraud and systemic errors need an overhaul on priority without getting fogged on private versus public ownership debate at this stage. While we may change ownership and improve competitiveness as a parallel exercise, strengthening regulator with real-time oversight mechanism and technologies is essential irrespective of the bank’s owner.

The key issue is neither fraud nor reputational loss for the banking sector. The key area of concern is the government’s clout is getting these culprits extradited. Had Mallya been an American, UK would have gone down in its knees to return him to the US. Where’s the clout that was pomposly projected at Madison Square and elsewhere? Or is this government deliberately pussyfooting on getting these people extradited because even some of their own are involved?

While the interest rates are being pushed down, the middle-class fixed income suffers while the high and mighty loot-and-scoot with impunity. So are we really a banana republic as the famous son-in-law once stated?

Just a rejoinder to Gurucharan Das.

He forgets subprime lending crisis which was created by private sector financial entities only. It doomed fate of a few private sector banks only.

Way back in 90s, Barrings Bank again a private bank fell because of greed of one individual.

Never home, he should not forget Global Trust Bank under NPA level in IndusInd Bank during first 5 years.

There is nothing like public sector or private sector. It is well managed and badly managed companies.

There are 20 other examples where crony capitalism was not followed by highest economic growth rates across the world. So please spare us the silver lining to what is a clear corrupt practice right now. Modi, Shah, Adani, Nikhil Merchant are not going to be around after 30 years to disprove this theory. India’s young generation will have to bear this burden of blatant crony corruption. Modi unleashed demonetisation on the country’s poor and middle classes. He is answerable for letting a jeweller (with really ghastly designs) run away with the money. He’s no different from Congress, at any rate. Maybe a touch worse with his Gujarat obsession.

Why privatise only the worst banks, the loss making PSUs, the Maharajah only when he is terminally ill ? Privatisation should be out of conviction, that it is good for the economy. As far as the PSBs are concerned, they have been drained out of all vitality. Not that the calls from Delhi will stop coming, but not enough sap in the tree to respond fully to them.