Data analysis shows that India’s overseas Test performance has dropped off a cliff since 2009, and Ravi Shastri’s ‘best away team in 15 years’ boast is false.

Beginning Thursday, Virat Kohli’s Indian cricket team will embark on what many experts are calling its best chance ever to win a Test series in Australia. The home side is severely depleted on the batting front thanks to the bans handed out to Steve Smith, David Warner and Cameron Bancroft, and combined with India’s much-improved bowling stocks, the experts might well turn out to be correct.

On India’s last tour abroad — to England earlier this year — coach Ravi Shastri had boasted that this was the best Indian touring team in 15 years, drawing much flak, since India haven’t won a series in a SENA (South Africa, England, New Zealand, Australia) country since 2009. In fact, India have never won a series in Australia or South Africa, won in England last in 2007, and in New Zealand in 2009.

So, what will happen Down Under this time around? Will the pundits and Shastri be proven right? While we may not have a crystal ball to gaze into, we do have the benefit of statistical analysis that can help us understand where the Indian team is headed.

Also read: Virat Kohli’s Team India best bet to beat Australia or are we taking home team for granted?

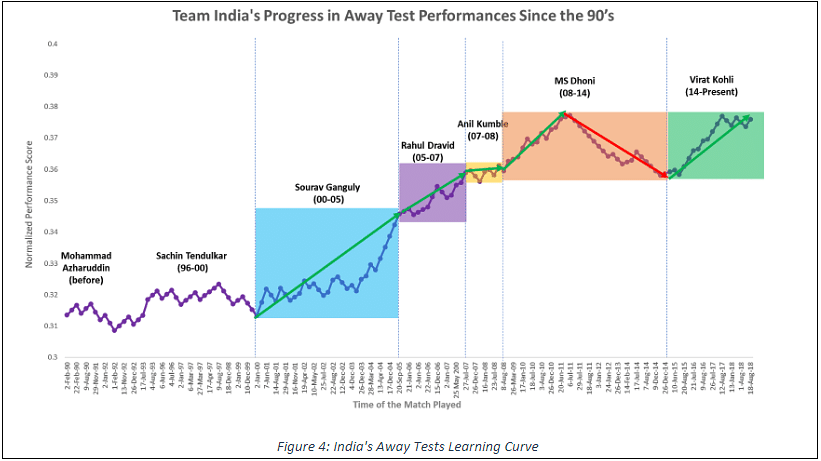

Using methodology called ‘the learning curve’, we find that the above optimism must be tempered. India’s Test cricket away from home is definitely on a downward spiral, and Kohli’s team cannot hold a candle to the Ganguly-Dravid era as travellers.

What is the learning curve?

Bruce Henderson, founder of the pioneering strategy consulting firm Boston Consulting Group, once said: “Good strategy must be based primarily on logic, not absolutely on experience derived from intuition.”

It might sound like disregarding the value of experience, but his firm was actually the first to introduce a concept pivoted on experience — the “experience curve”, or the learning curve.

The concept has since been applied in many industries, organisations, institutions and even individuals. It means when people or organisations repeat a process and gain skill or efficiency (from their experiences) over time, it brings about improvements in results.

With the learning curve, it is possible to build a continuous graph of the Indian cricket team’s performance over the years.

How to adapt it to sport

In order to contextualise it for the sporting world — to see the country’s performance in a time-series — the following learning curve model can be devised:

Step 1: Tabulate all the matches the team has played in chronological order with outcomes (win, draw/tie and loss).

Step 2: Assign one, half and zero points respectively for a win, draw/tie and loss.

Step 3: Calculate the cumulative points earned by the team at the end of each match.

Step 4: Divide the cumulative points by the match number to arrive at a team’s ‘Normalised Performance Score’ (NPS) till that match

Step 5: Draw the learning curve with horizontal axis as the time or the game numbers, and the vertical axis as the NPS.

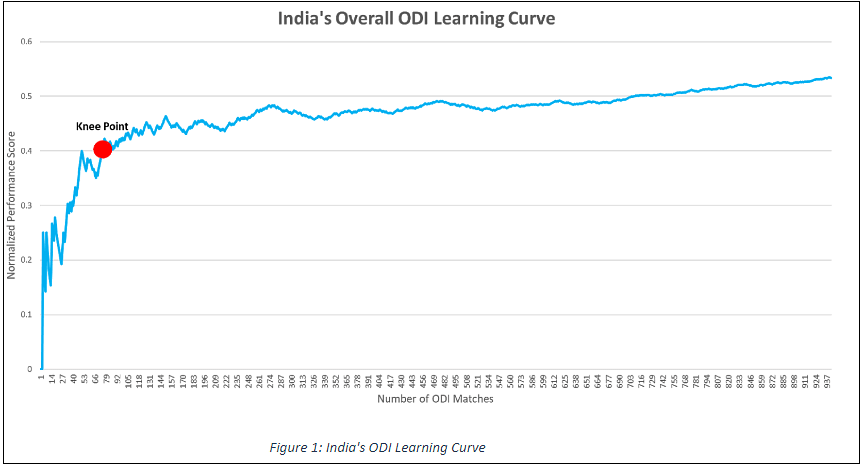

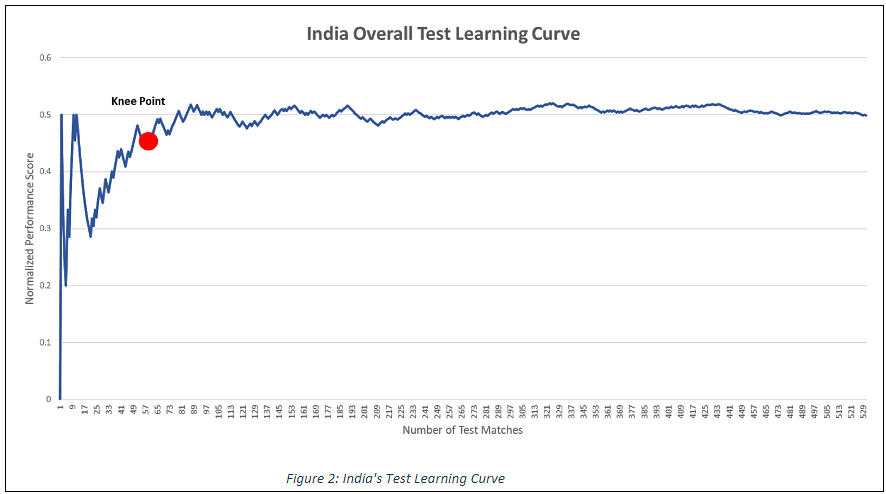

India’s overall ODI (since 1974) and Test (since 1932) learning curves are as shown below:

A relay race, not a random sprint

With a sufficiently large sample size, the curves exhibit two striking patterns. One, teams go through torrid times initially and then make rapid progress. Second, once the performance score reaches the ‘Knee Point’, performance tends to stabilise, and improvement subsequently comes about at a sluggish rate.

Teams, however, take different times to reach the ‘Knee Point’, and show different rates of improvement or decline past that point.

Such patterns mostly hold true across teams and formats, particularly Tests and ODIs, since the sample size is not large enough yet for T20Is. Exceptions like the West Indies or Zimbabwe come about due to disruptions — political, cultural or socioeconomic.

In a learning curve study, the performance is a continuous curve, not discrete data points such as the percentage win or loss under a captain or an era. When Kohli takes the team to a certain performance level, he does so on the foundation laid by his predecessors, not arbitrarily and not in isolation. The curve links the Kohlis and the Dhonis in the same thread as the Kumbles, Dravids, Gangulys, Tendulkars, Azharuddins and their forerunners. The learning curve in that regard is a relay race, not a random sprint.

The ‘twenty-thousand-feet-level view’ — spread over hundreds and thousands of matches — shows nothing more glaring than the pattern mentioned earlier. A closer look, however, throws up some thought-provoking observations.

The IPL disruption

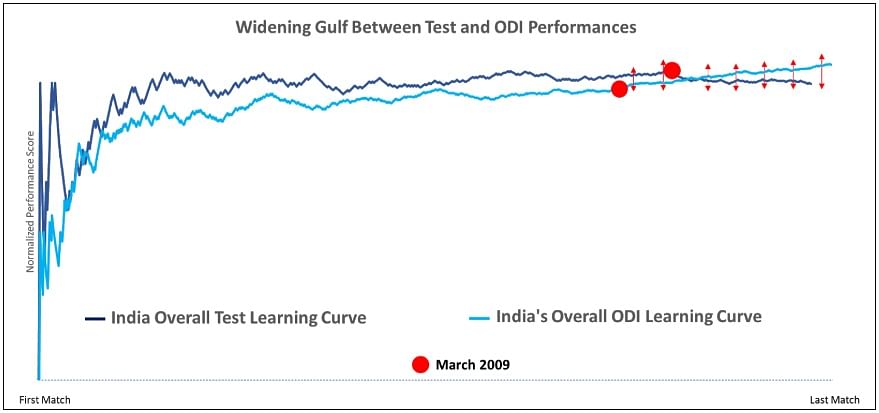

A closer look at the Test and ODI learning curves shows that Indian cricket has moved in different directions in the last decade or so. While India’s ODI performance graph has steadily gone up, the Test curve has slid rather sharply.

In March 2009, the two curves crossed each other. India’s 430th Test match against New Zealand at Hamilton represented the peak of the curve in the last decade — since then, it has lost the upward drift by about 4 per cent. This, as mentioned above, was India’s last series win in a SENA country.

On the other hand, India have done remarkably well in the ODIs since. The performance score was precisely 0.5 (representing an even win-loss ratio) in March 2009, and it has improved by 7 per cent since then. Over such a large sample size spread over decades, performance score doesn’t change much, so a 4 per cent drop and a 7 per cent rise are significant numbers.

How does one explain this? It is, of course, tempting to link this to the advent of the IPL a year earlier, in 2008, which triggered an unparalleled white-ball cricket craze in India, touching the lives of cricketers, administrators and fans differently but definitively.

The two curves tell a story of how the IPL has been a disruption to the game, affecting the technique, management and performance of the sport in India.

Ganguly and Dravid drove unprecedented acceleration

Shastri’s ‘best in the last 15 years’ boast is not just misplaced, it also ignores the unprecedented acceleration provided by Sourav Ganguly and Rahul Dravid as captains of India. The learning curve speaks for itself when it comes to India’s overseas performances since the 1990s.

Also read: Rahul Dravid now stands head and shoulders above the gods of cricket

The paradox that was the Dhoni era

The trophies a team wins — especially World Cups and World T20s — do add to national prestige and arouse positive sentiments, but they often blur our vision. They don’t always represent the true story of a team’s progress over time. Learning curves, however, look at such events with detachment.

Such dispassionate ways of looking at things suggest that the era of Mahendra Singh Dhoni, probably the best among all Indian captains, was a paradox. The learning curve shows that he actually took Indian cricket backwards with dismal overseas performance in Tests.

Under Dhoni, India’s away Test performance score touched an abyss that was already left behind in the pre-Kumble era. It is equivalent to dragging back Indian cricket by six years.

Winning Test away matches is a culture, or to use Dhoni’s own oft-repeated word, a “process”. It is a result of methods refined over time, passing on vital on-field and dressing room values to future generations, finding the right talent and even helping the governing board devise key strategies to that end.

India haven’t won a Test series in the difficult touring countries abroad in nearly 10 years, and it’s not because of the mysterious ailment of “failing to seize key moments”, as the pundits call it. It is, in fact, a chronic disease that is a result of malpractices through the last decade.

Dhoni, no doubt a great contributor to the Indian game, also carries the stigma of severely impairing the ‘winning away’ culture that India had achieved through years of honing.

This is what ought to be giving captain Kohli huge concerns ahead of the ‘best chance ever’ Test series Down Under.

The story of the curved lines unpacks pastures of promise for India’s limited overs cricket, and patches of pitfalls for the longer format. To justify its ‘cricketing superpower’ tag, India must reverse the trend of away Test results.

This series in Australia is the best opportunity to do that.

Debnath Roychowdhury is an alumnus of NIT Durgapur and SPJIMR Mumbai, and currently works as a management consultant.