Most people of my generation got their first exposure to the complexities of national politics through the dark phase of the Emergency. And as it lifted, peer pressure in the hostel messes was intense to go and work for the then Janata Party candidates taking on the Emergency gang. At the Punjab University campus in Chandigarh we also had a good candidate, former Congress Young Turk and rebel (the late vice-president of India) Krishan Kant. Literally hundreds of students bunked classes to go paint the town with his posters, and anti-Emergency slogans.

Now what, you might wonder, is the relevance of this three-decade-old story ‘ a common occurrence in early 1977 ‘ to the raging issue of OBC reservation in institutions of higher learning?

Well, let’s go back to 1977. Elections swept, Krishan Kant found a few moments in that heady aftermath to thank his student volunteers. Of course he delivered a small speech condemning the Emergency and extolling Jayaprakash Narayan and his brand of socialism. Then he added, in sheer gratitude, “I thank you for what you have done for me and for democracy. Please come to me if you need any help. And, whenever each one of you gets married, please see me. I will give you a coupon for an LPG connection out of the MP’s quota.” So much for a reward of that stirring victory against authoritarinism ‘ a gas connection when you got married!

So, remember that dark phase in our history from our own lifetimes. When a gas connection, a Bajaj scooter, a telephone connection were all part of the largesse the political class could dispense to our eternal gratitude. Or, we had the option of waiting in line for 15 years.

Fifteen years of reform have changed all that. In fact, our children today would find these stories of man-made, self-inflicted scarcities and atrocities entirely unbelievable.

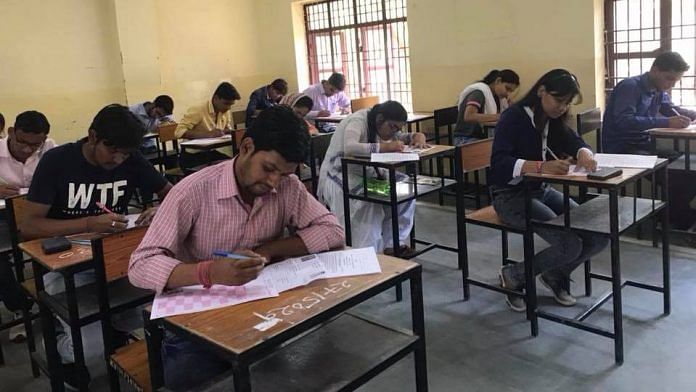

As incredible as, hopefully, their children would find stories of today’s even more cruel, self-inflicted atrocities. A total of 4, 000 seats in all our IITs, just around 1, 500 in all our IIMs, a mere 50 MBBS seats per year in AIIMS, a ridiculous total of 235 for graduate diploma and post-graduates put together at the National Institute for Design, only 480 students at National Law School, and so on. That is why today’s spectacle of a mere three to four per cent of all eligible applicants making it to these institutions, of 90-percenters failing to find decent courses in Delhi University colleges, is today’s equivalent of the pre-1991 fifteen-year wait for scooters, gas connections, telephones.

The anger you see on the streets of your cities, the bitterness that motivates normally pampered and softie medical students to endure hunger strikes to rival Medha Patkar’s, comes out of this frustration. And here is my central point. If the economic crisis, the near default of 1991, which arose from two years of totally disastrous economic management under V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar gave Finance Minister Manmohan Singh the opportunity to turn that 15-year wait for basic necessities of transport, household fuel and communication into a situation of unlimited plenty, his own colleagues’ crude push for OBC reservations brings an opportunity to similarly rejuvenate higher education.

Also read: Doing the ‘Right’ thing

Why do people like Arjun Singh (and the Mandalite chieftains who still reap the harvest of votes at the expense of the Congress) think OBC quota is such a potent weapon to slay whichever demons that are out to get them? Why should a step that will, at best, get two to three thousand (only that many, you can count again) OBCs into these institutions bring them so much political gain, whether in terms of votes or sheer revenge on a rival, or fate? Because this handful of seats in these institutions is today’s equivalent of Krishan Kant’s LPG coupons. Here is something the politician denied you in the first place. And here is something he can give you: his generous largesse if you give him your external gratitude and, of course, vote.

Would it have been the same way in 1977 if LPG was available off the shelf? Would it be the case now if India had, instead of 5, 000, some 50, 000 IIT seats? Or 10, 000 in the IIMs, 500 at AIIMS in Delhi, another two lakh in medical colleges elsewhere instead of 18, 000? This artificial scarcity is not just the mother of today’s frustration. It is actually a festering national crisis. Since higher education seemed to concern so few, it was on nobody’s political radar screen. Even the most ideologically pro-active HRD ministers like Murli Manohar Joshi and Arjun Singh would never have seen any need to focus on it. But this self-destructive quota crisis which Arjun Singh has walked his party into changes all that. Suddenly, higher education comes to political centrestage, breaking out of a time warp where the political discourse was confined to Sarva Siksha Abhiyan and mid-day meals.

The total government control over higher education has produced a scandalous state of self-denial and man-made scarcity. We believe our advantage in the global marketplace comes from our superiority in technology, mathematics, sciences. Can we do that on the back of 5, 000 IIT graduates per year? It might be sobering to look at some global comparisons.

The MIT alone takes as many undergraduates per year (4,000) as all of our IITs. Harvard Business School alone takes 900 students every year and Harvard Law takes 1, 800 ‘ almost 400 per cent of our NLSUI of Bangalore. Is that how a modernising, growing India, its economy driven by the engine of services and manufacturing, is going to find its rightful place in this globalising world?

But how can you compare our situation with America’s? We have a per capita income of $700, they have $22, 000 per year, so the argument will, predictably, go. Similar arguments were used to keep gas connections, scooters, cars and telephones in short supply for nearly four decades after Independence. And what happened when you opened up? The tax payer did not have to spend a paisa more. And today we are acknowledged to be a rising global power in car manufacturing, the second fastest growing telecom market, and coupon books for MPs’ LPG quota went out of print years ago.

But there are areas where they still remain. An MP can still give you a coupon or a letter for admitting your child to a Kendriya Vidayalaya. Please go and stand outside the HRD minister’s house next month and you will find hordes of ordinary people waiting for help in getting their children some reasonable education unmindful of the signboard that firmly tells those seeking Kendriya Vidayala admissions not to crowd the entrance.

Why would the minister now use a part of his hoard (particularly after the education cess) to build a couple of hundred more Kendriya and Narvodaya Vidyalayas, to expand and build new IITs and IIMs? He won’t because he will then lose the power of the coupon and the quota. And his bureaucrats won’t allow it because this is by far the most important area of our economy they can still fully control. The power of keeping an IIM director waiting for weeks for his joint secretary’s clearance to attend a prestigious foreign conference is heady. More institutions, more seats, private investments all add up to the loss of that power.

This is the last ‘ but perhaps the most destructive ‘ relic of the licence quota raj. The quota crisis, and the fortuitous arrival of higher education on the political centrestage is in many ways similar to the other crisis that led to India mortgaging its gold to escape payment defaults. Finance Minister Manmohan Singh managed to convert that crisis into an opportunity that changed our lives. Can he similarly in today’s crisis in higher education do the same for our children? Surely, this situation is no less daunting in its risks and complexities. But the rewards of expansion, opening up, private investment, genuine administrative and intellectual freedoms in a society that lays such a premium on education and scholarship will be no less significant.

Also read: Ears wide shut