Bengaluru: The explosive eruption of the Hunga Tonga volcano last Saturday was the biggest volcanic event recoded anywhere in the world in over three decades, say experts. For the volcano itself, it was a once-in-a-thousand-years event.

Situated in the Kingdom of Tonga in the Pacific Islands, the volcano has sunk under the ocean; its vent (opening) was already submerged before the eruption.

The eruption produced an ash cloud 260-km wide and rising up nearly 39km into the sky, by early estimates. Within the cloud were electric storms that produced up to 400,000 lightning strikes in three hours.

The volcanic eruption also triggered a tsunami causing waves over a metre high across the Pacific Islands, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, as well as the west coast of North and South America. This was the first instance of a volcanic eruption causing an ocean-wide tsunami in the Pacific instead of an earthquake. The tsunami waves were also unusual in their characteristics, stumping experts.

A massive shockwave followed the eruption and was observed from space in stunning satellite imagery. The wave was recorded in seismometers around the globe — including in distant Alaska, over 9,000km away.

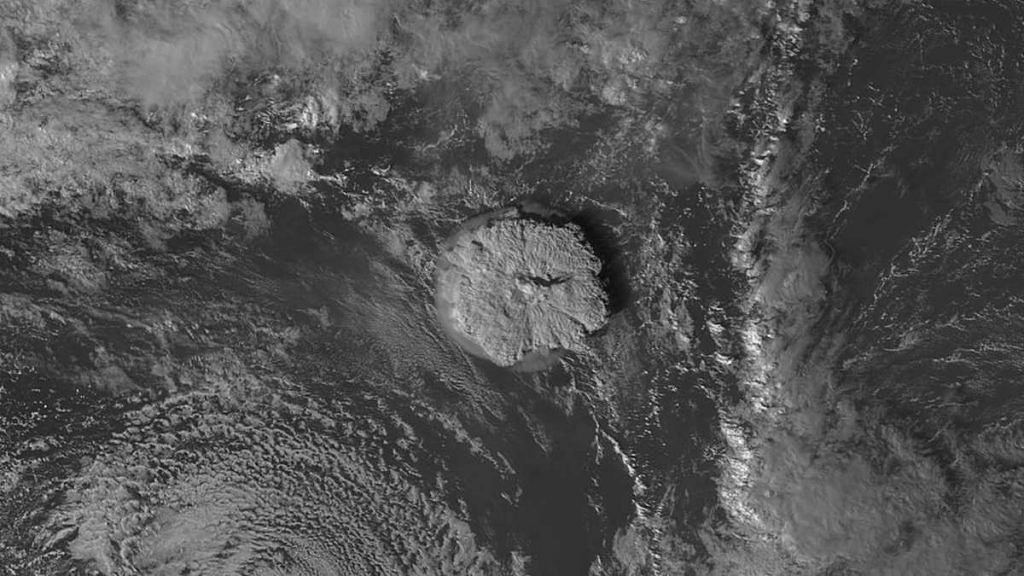

Here is a sequence of @planet imagery leading up the massive eruption in #Tonga (images 1–3), & post-eruption (image 4).

Hunga Tonga & Hunga Ha'apai were 2 separate islands that connected from the growth of the volcano between them ~7 yrs ago. They are now disconnected again. pic.twitter.com/gnijplvteE

— Dr. Tanya Harrison (@tanyaofmars) January 18, 2022

This fallout, expectedly, has been serious.

The eruption has downed an undersea communication cable that it is estimated will take two weeks to fix, leaving citizens of Tonga in a communications blackout. Some domestic telephone lines have been restored, but the thick ash deposit from the explosion is making it difficult for planes carrying aid to land.

Three people are reported to have died — one in Tonga and two off the coast of Peru from 2-metre-high tsunami waves. Tonga and other Pacific Islands, including Fiji, also experienced 2-metre-high waves that destroyed settlements and houses. The coastlines of some islands have been submerged, while multiple uninhabited islands in Tonga have gone completely under.

The ash deposit from the eruption is expected to cause environmental damage for a few years. After blocking out the sun in Tonga, the cloud has since started to disperse, moving over Australia and into the Indian Ocean, but no global climate impact is expected.

The eruption Saturday has been the most powerful eruption since that of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines in 1991. What caused the sinking of the volcano is still unclear. Because the volcano is remote, and is now underwater, performing observations close-up has been difficult for volcanologists.

The eruption event itself is still ongoing and more eruptions cannot be ruled out, experts say.

Also Read: Shaken by 18,000 quakes in over a week, Iceland braces for 800-year dormant volcano to erupt

Unfamiliar eruption

The now-submerged volcano is located between the two islands of Hunga Tonga and Hunga Ha’apai in the Kingdom of Tonga. The region sits on top of the Ring of Fire, a tectonically active horseshoe-shaped region that runs along the east of Australia and NZ, along South-East Asia and Japan, along the Bering strait, and down the west coast of the Americas. These regions produce the majority of volcanism and earthquakes on the planet due to tectonic plates interacting with each other.

Tonga sits on top of a fault or intersection, where the Pacific plate is sinking under the Australian plate. This process, known as subduction, causes warm water in the sinking plate to rise up and mix with magma, making it viscous. This traps a lot of the heated water as bubbles, building up pressure, and leading to eruptive events.

It is still unclear what triggered an explosion of this magnitude, but superheated magma at over 1,000 degrees C rising up to come in contact with shallow oceanic water at 20 degrees C intensified it.

“Adding water to the mix in this way makes the explosion more violent,” explained Dr Janine Krippner, volcanologist at the Smithsonian Global Volcanism Program. “When hot magma interacts with water it flashes to steam rapidly, adding more fuel to the eruption so to speak.”

However, the scale of the eruption and its impact is very large for this volcano, say researchers.

“We honestly don’t know what exactly happened during this massive blast. The magma clearly interacted violently with sea water and that released an enormous amount of energy, that’s what we do know,” added Krippner.

What caused the volcano itself to sink is also unclear, but the vent was already underwater before Saturday’s eruption.

This has made both understanding the eruption and follow-up observations of the volcano very difficult even as the volcano continues to spew material as a part of the ongoing eruption event.

Volcanologists also say that the amount of material released by the volcano is surprisingly little compared to the scale of the blast.

Shockwave seen from space

The explosive eruption produced a shockwave that was clearly observable on satellite images. This shockwave travelled across the globe at the speed of sound, and was recorded around the world as both a pressure wave and an acoustic signal.

Most instruments globally recorded the shockwave twice, one from the direction closest to Tonga, and the other from the opposite direction, due to the part of the wave emanating from the other side of Tonga.

In Germany two main air pressure waves from the #Tonga eruption could be detection: The first wave traveled from north to south, while the second wave moved from south to north. The reason might be explained by the animation below, where I visualized an outgoing circular wave… pic.twitter.com/B57uRyy3ik

— StefFun (@StefFun) January 16, 2022

The accompanying sonic boom was recorded in many places, and reached Alaska, over 9,300 km away, after seven hours.

Wow this is terrifying, the type of sonic boom you hope you never hear. That is a staggering pressure spike. [NSFW language]

Hoping everyone in the vicinity of the Tonga volcanic eruption is staying safe

shared from Facebook by @WhiteHaTterz pic.twitter.com/Yb8eGNohXN

— Chris Combs (@DrChrisCombs) January 15, 2022

It travelled around the world twice, converging in Algeria before radiating to Tonga and back again.

Tallest ash column

The eruption also produced possibly the tallest-known ash column of an eruptive volcano. When activity began on 20 December, the ash being emitted from the vent climbed up 16km into the atmosphere. On 14 January, after the eruption, the ash column rose up a further 10km.

Some early calculations show that the ultimate height the ash reached directly from the volcano was 39km. If this number is confirmed, this is the highest that a cloud from a volcano has reached.

Volcanic emissions can inject large amounts of sulphur dioxide (SO2) into the atmosphere, which can act as a global coolant. In the stratosphere above 10km, the gas reacts with water and turns to sulphuric acid aerosols in the atmosphere, which in turn block incoming solar radiation. This can cause earth to cool.

Initial data suggests that the amount of SO2 released is not enough to cause any significant impact on global climate. However, it is still unclear if more eruptions might occur, causing an increase in SO2 concentrations.

As the ash cloud disperses higher up in the atmosphere, it is being converted into sulphuric acid aerosols. The winds blew the ash over Australia, causing spectacular sunrises on Monday morning. It is now moving over the Indian Ocean.

Ash fall from volcanic eruptions can cause extensive environmental damage and crop failure.

Currently, in Tonga and on other Pacific Islands, there is a thick layer of ash deposited on everything. This ash mixes with soil, making it more acidic. The ash can also lead to acid rain, which could damage crops.

Mysterious Pacific-wide tsunami: ‘A damn scary event’

The eruption led to the very first recorded tsunami in the Pacific caused by a volcanic explosion, Krippner said.

Typically, tsunamis are triggered by earthquakes more than they are by volcanoes. The ones that do follow volcanoes occur because of the collapse of the volcano, which deposits large amounts of material into the ocean, displacing water.

However, it appears as if the movement of water in this instance was triggered directly by the force of the explosion itself instead of a collapse. What exactly caused the tsunami — whether it was the displacement of the sea floor or the impact of the ash falling back on water or the shockwave moving the water — is yet to be understood.

Japanese authorities stated that the tsunami that occurred at their coast from the volcano did not have characteristics similar to a regular tsunami, and they couldn’t explain how it was generated.

“There are several ways to trigger a tsunami during an eruption, they all need to displace a large amount of water,” explained Krippner. “We can see that a lot of land mass was removed, but we can’t say for certain how yet.”

“This is the first instance that we have witnessed of a volcanic eruption triggering a Pacific-wide tsunami,” she added. “This is a damn scary event!”

The waves from the tsunami reached a height of 2 metres in Tonga and other Pacific Islands, wiping away some settlements and houses. The tsunami radiated across the Pacific, hitting the coasts of Australia, New Zealand, and Japan with waves over a metre high. It also hit the west coast of the Americas, causing flooding in North America. It caused more damage in South America with the coasts of Chile, Ecuador, and Peru experiencing high waves.

Record electric storm

The volcano set off a powerful electric storm in the ash cloud.

Electric storms generate lightning strikes, which are common in volcanic eruptions when ash is climbing up into the skies. Particles of dust and ash rub against each other producing static electricity, isolating positive and negative charges, and discharging lightning.

As the ash climbs even higher into the colder parts of the atmosphere, particles start to rub against ice crystals, amplifying the effect. When an eruptive event is intensified because of contact with water, the ash produced is even finer, leading to more particles causing more electric discharges.

Tonga’s lightning flashes were detected by the Global Lightning Detection network (GLD360), and it recorded the expected hundred to thousands of flashes a day. But, at the peak of the January event, it detected 200,000 discharges an hour.

Some hourly statistics from this latest #HungaTongaHungaHaapai #HungaTonga #Volcano Eruption.

Peak hourly rate was 200,000 discharges between 0500 and 0600 UTC!

Just absolutely amazing. https://t.co/mDVFfAHd6B pic.twitter.com/W5IdO2TES5

— Chris Vagasky (@COweatherman) January 15, 2022

Over 400,000 lightning events were ultimately recorded in a matter of three hours. The strikes also hit the unoccupied ground and waters in the area.

This is the most incredible #lightning loop that I have ever put together. #HongaTongaHungaHaapai #HungaTonga #Volcano eruption today with nearly 400k lightning events in just a few hours! pic.twitter.com/xqW70NLeVd

— Chris Vagasky (@COweatherman) January 15, 2022

Human impact

The event has left approximately 100,000 Tongan citizens to deal with hazards and destruction. A distress call was detected from the low-lying islands of Fonoifua and Mango.

So far, authorities have stated that two Tongan nationals and one British national have died on Tonga from the volcano and tsunami. Two people died off the coast of Peru from 2m high waves. An oil spill that occurred off the coast of Peru was also blamed on large waves.

The ash from the event has caused damage to infrastructure and thick deposits have made it difficult for recue and aid planes to land in Tonga. Experts fear that ash inhalation may also lead to health issues, including lung damage and skin irritation.

Communications across the Tongan islands are yet to be restored fully, and an undersea line that got damaged is expected to take two weeks to get fixed, authorities say.

The causes and effects of this intense eruption are yet to be completely understood, owing in large part to the volcano being underwater. In general, underwater volcanoes are more inaccessible and less well studied.

Despite the activity continuing to steadily decline in Tonga, volcanologists and local authorities are continuing to monitor the ongoing eruption without ruling out another, albeit smaller scale, explosive event.

(Edited by Asavari Singh)

Also Read: Lightning killed over 100 people in a day in Bihar & UP. This is how the phenomenon occurs