New Delhi: Humans likely produced and consumed beer and blue cheese as far back as 2,700 years ago in Europe, researchers have found in a first that sheds light on the eating habits of our prehistoric ancestors.

For the study, researchers from Eurac Research Institute for Mummy Studies in Italy and Museum of Natural History Vienna analysed faecal samples found in the ancient salt mines at the Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut Cultural Landscape, a UNESCO World Heritage in Austria. The findings were published in the journal Current Biology Wednesday.

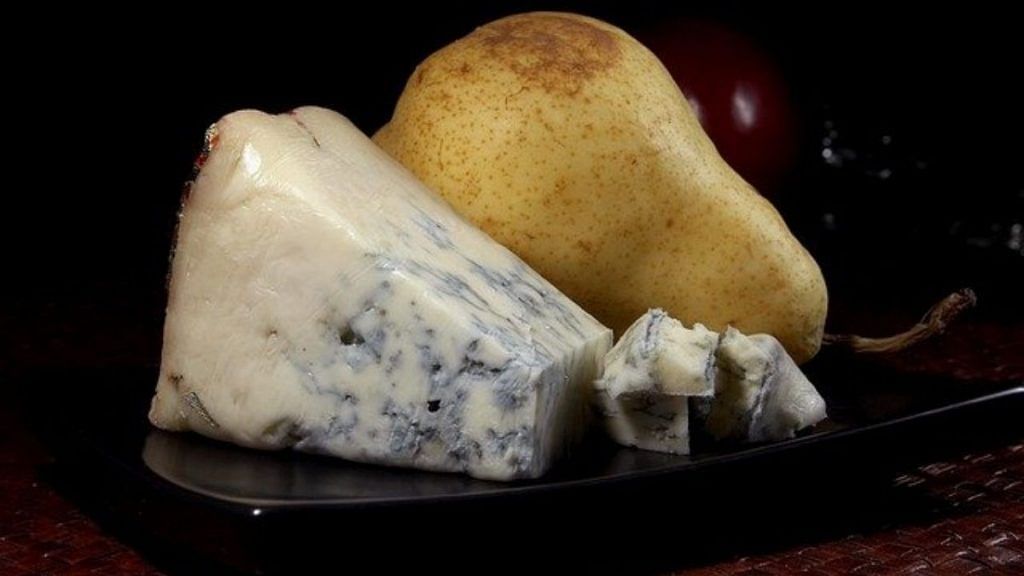

This is the first evidence that blue cheese was being produced in the Iron Age, which is defined as roughly the period between 1200 BCE and about 500 BCE.

Human faeces usually tends to decompose quickly, hardly ever leaving any trace behind. However, salt mines often provide perfect conditions to preserve organic matter for thousands of years.

In faecal samples or paleofeces from these mines in the Hallstatt-Dachstein/Salzkammergut Cultural Landscape, researchers found the presence of two fungal species used in the production of blue cheese and beer. They analysed microbes, DNA, and proteins that were present in the samples.

The study allowed the team to get information about the ancient microbes that inhabited the guts and helped them reconstruct the diet of the people who once lived in the area.

“Genome-wide analysis indicates that both fungi were involved in food fermentation and provide the first molecular evidence for blue cheese and beer consumption during Iron Age Europe,” said Frank Maixner of the Eurac Research Institute for Mummy Studies in Italy, in a statement.

Also read: Microfossils suggest our ancestors interacted with some early humans in Thar Desert, study says

Highly-fibrous, carbohydrate-rich diet

Researchers found evidence of bran and glumes of different cereals as one of the most prevalent plant fragments. This highly fibrous, carbohydrate-rich diet was supplemented with proteins from broad beans and occasionally with fruits, nuts, or animal food products, according to the team.

The ancient miners had gut microbes that resembled those of modern individuals whose diets are mainly composed of unprocessed food, fresh fruits and vegetables.

The findings suggest that the Western gut microbes shifted more recently than earlier thought as eating habits and lifestyles changed.

However, the biggest surprise for the team was an abundance of DNA of two fungi — Penicillium roqueforti and Saccharomyces cerevisiae — which are used in the production of beer and blue cheese.

“The Hallstatt miners seem to have intentionally applied food fermentation technologies with microorganisms which are still nowadays used in the food industry,” Maixner said.

“These results shed substantial new light on the life of the prehistoric salt miners in Hallstatt and allow an understanding of ancient culinary practices in general on a whole new level,” said study author Kerstin Kowarik of the Museum of Natural History Vienna, in a statement.

“It is becoming increasingly clear that not only were prehistoric culinary practices sophisticated, but also that complex processed foodstuffs as well as the technique of fermentation have held a prominent role in our early food history,” she added.

(Edited by Rachel John)

Also read: How we feel temperature and touch: Research that won US scientists Nobel Prize in medicine