Boston: The stage looks all set for the 1941 general election, and the 1941 Cricket World Cup is just months away. India will complete 100 years of Independence in 1969.

Confused? Don’t be. The years might seem all over the place, but it’s only because India, like much of the rest of the world, follows the Gregorian calendar. However, few know about the ‘Indian National Calendar’ that has existed since 1957, which begins three months into the conventional year and ends in March as well.

In the world of the Saka samvat, or the Indian National Calendar, there are 12 months, and the names are all different. ThePrint tells you all about it.

A problem of plenty

When India got Independence, there was no uniformity in time reckoning. Simply put, India had too many calendars.

Jawaharlal Nehru, the country’s first Prime Minister, observed that the numerous calendars were a natural consequence of India’s political and cultural history.

While Muslims followed the Hijri calendar for observing Islamic festivals, the majority of the country’s Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains followed a Hindu calendar, or panchangam. These almanacs were uniquely crafted for each locality, and there were about 30 of them.

Thanks to India’s tryst with the British, however, the Gregorian calendar retained primacy, despite being an unscientific instrument that is not completely in sync with the solar year.

This led to the state of calendars in India to become confused.

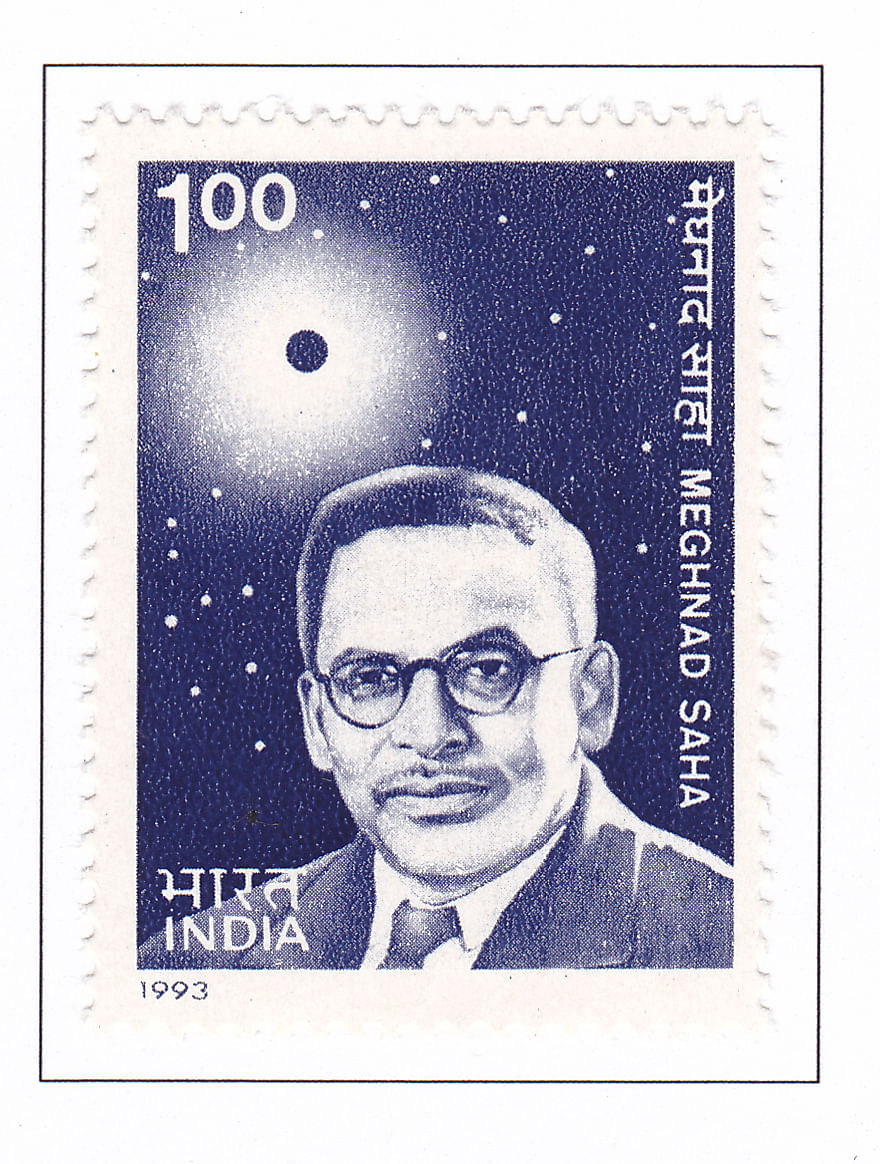

To bring uniformity and accuracy to time-reckoning, in 1952, the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research constituted a calendar reform committee under astrophysicist Meghnad Saha.

Saha’s astronomical challenge

Saha realised at once the enormity of the task at hand: To untangle the Gordian Knot of different Indian calendars was — both literally and figuratively — an astronomical challenge.

“Astronomy [is] the first of all sciences,” Saha wrote in India’s Calendar Confusions, a paper published in the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada in June 1953. “[And the] oldest of astronomical problems is the calendar.”

The calendar reform committee studied all the different calendars in India and went deep into the history of calendar-making and time-reckoning.

Reforms for the Islamic (Hijri) calendar had already been proposed by scientists at Osmania University. In the 1950s, the UN almost took up a proposal to abandon the Gregorian calendar in favour of the World Calendar, a reform that suggests a year with four equal quarters that remains the same forever (for example, 1 March will always fall on the same day).

However, it was not adopted in light of the several objections, many of them religious, raised.

With these efforts underway, the committee confined itself to examining different systems of calendars used by the Hindu, Buddhist and Jain communities.

Also read: Uranus remains mysterious but now we know why it spins on its side

Inconsistencies and inaccuracies

In examining the various panchangam calendars of India, Saha and his committee found discrepancies of two kinds.

First, there were problems due to inconsistencies, which primarily arose due to conventions.

The convention of almanac-makers at the time was to calculate specific moments for each locality. Additionally, a day was defined with respect to the rising and setting times of the sun and the moon. A consequence of this was that a specific moment may not occur on the same day in all places. As a result, the same auspicious moment was sometimes observed on different days in different places.

Second, there were problems due to inaccuracies, born of errors in observation.

Almost all panchangam calendars were published by following rules laid out in the Surya Siddhanta, an astronomical treatise written around 500 AD. The length of a year, as measured by the Surya Siddhanta, was 365.258756 days.

However, Saha observed that the actual length of a year was 365.242196 days. The Surya Siddhanta year was longer than the tropical year by 0.01656 days.

This error had accumulated over the span of 1,450 years to amount to 24 days. Thus, the Hindu calendar months had undergone a shift in seasons. The consequences of this 24-day shift were evident to Saha.

Traditionally, those following the solar calendar observed the year’s beginning on the Vernal Equinox (first day of the astronomical spring in the Northern Hemisphere, which can fall on 19, 20 or 21 March).

However, Saha saw that a sizeable population observed their regional New Year’s Day on or around 14 April — exactly 24 days after the Vernal Equinox.

A national symbol is born

Having diagnosed the problems facing the different calendars in India, Saha and the committee created a new, scientifically accurate, all-India National Calendar: The Saka calendar.

The Saka calendar marked its new year on the Vernal Equinox. Its months, which began from Chaitra and ended with Phalguna, were either 31 or 30 days long. It used the Saka era to count years.

Along with the Saka calendar, Saha and the committee made recommendations regarding how different local almanac makers should make calendric calculations. They also laid out the precise dates on which certain religious festivals ought to be observed.

“[The] National Calendar,” Saha wrote in India’s Calendar Confusions, “[will] prove not only a boon but also a great unifying factor in our country.”

The Government of India officially started using the Indian National Calendar on 1 Chaitra 1897, or 22 March 1957.

Today, the Government continues to use this calendar along with the Gregorian calendar for official purposes.

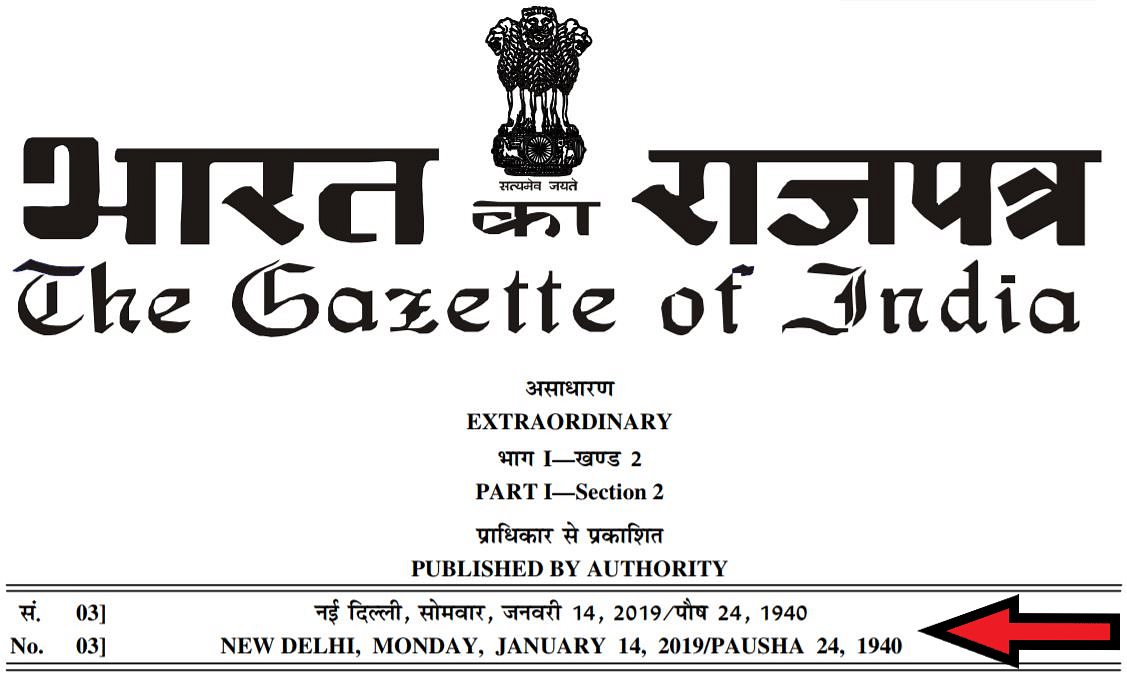

However, the use of the Indian National Calendar seems to be restricted to such entities as the Gazette of India, and All India Radio.

Nehru was aware of the possibility that the Indian National Calendar may not find the universal adoption it set out to achieve.

“It is always difficult to change a calendar to which people are used,” Nehru wrote in the PM’s message that accompanied the report of the calendar reform committee. “But the attempt has to be made even though it may not be as complete as desired.”

Saha recognised this possibility too. “It is a simple lesson of history that only dictators and religious leaders wield the power to impose such measures of reform,” he wrote in India’s Calendar Confusions.

“The mere enactment of an all-Indian National Calendar is not sufficient, for it may become a dead letter. There [should be] a living organisation to work out details, [and] to carry on a persistent educational propaganda program.”

Also read: It’s all in the stars: Indian astrological texts are full of queer predictions for mortals

Abhinav Srinivasan lives in Boston and works in the tech industry. You can follow him on Twitter @thexfactorial.

The Saka Samvat year for the general election and the Cricket World Cup was earlier erroneously mentioned as 1940. It should be 1941 and has been updated.