New Delhi: Maharashtra Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray is miffed with the Narendra Modi government at the Centre for not invoking its power to give reservation to the Marathas, after the Supreme Court on 5 May struck down the state’s ability to grant such benefits to this powerful community.

The apex court has ruled that the power to include or exclude a community for reservation like the Marathas lay with the President (read, Centre). The President, after consultation with the state’s Governor, may specify such Socially and Economically Backward Classes (SEBC), the court said.

Maharashtra argued that the Centre, therefore, can notify SEBCs for reservation. It has the power to do so under the 102nd amendment, which the Supreme Court has also ratified, it said.

But instead, the Centre has only filed a petition urging the apex court to review its majority judgment that deprives the state of its power, the government said.

Thackeray has sent repeated missives to PM Modi and Governor Bhagat Singh Koshyari to intervene in the Maratha reservation issue.

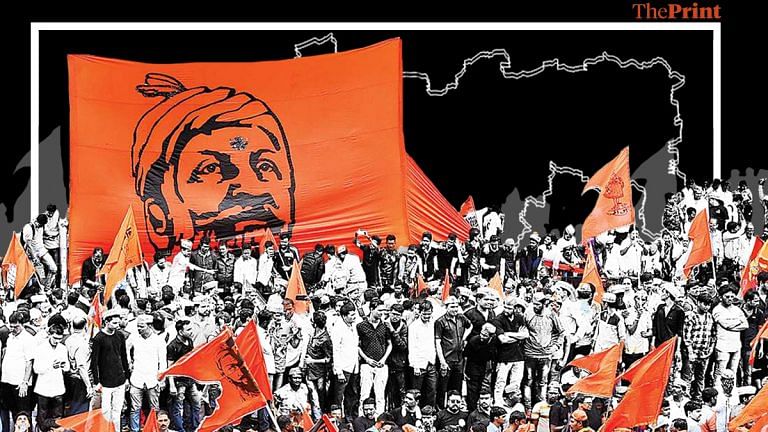

In November 2018, the then BJP-Shiv Sena government accorded reservation to the Marathas via an Act passed in the legislative assembly and council. The Bombay High Court, while upholding the Act, mandated that the quota be 12 per cent in education and 13 per cent in jobs.

This, however, raised the reservation to 64 and 65 per cent, respectively — higher than the 50 per cent ceiling mandated by the Mandal Commission — and brought the matter to the Supreme Court.

The five-judge Constitution Bench ruled early May that there were no “exceptional circumstances” or “extraordinary situation” in Maharashtra that required the state government to exceed the 50 per cent ceiling for the Marathas.

The Bench placed the ball entirely in the Centre’s court on the issue.

Also read: New backward class lists to be drawn, 50% ceiling stays — what SC Maratha quota verdict means

Why is Centre hesitant to use its power?

The judgment has put the Centre in a peculiar position. If it uses its power under the 102nd amendment, it will have to answer similar demands for reservation from other states.

If it doesn’t, it faces a political challenge from the Marathas, who account for 32 per cent of Maharashtra’s population. Other agitating communities in various states will also be up against the Centre.

Political analysts argued that given the challenges thrown by the Covid pandemic, the faltering economy and the farmer agitation, the Centre could not afford to court another controversy by notifying reservations in each state and union territory.

For example, the Patels in BJP-ruled Gujarat — a dominant caste in the state — wanted reservation after the Patidar agitation. The state government in 2016 issued ordinance to provide 10 per cent reservation but this was later struck down by the Gujarat High Court. In the 2017 Assembly polls, BJP did not get the Patel vote.

Same with the Jats in Haryana. After violent protests in February 2016, the state government enacted a law to give 10 per cent reservation to Jats and five other castes in jobs and education. But the Punjab and Haryana High Court put the law in abeyance.

If the Centre now accepts the Maratha demand, everybody will be at its door asking for reservation.

All India Jat Arakshan Sangharsh Samiti chief Yashpal Malik said: “We will soon call a meeting of Jats, Patels and Marathas to request court to strike down reservation in other states that violates the 50 per cent ceiling.”

A senior BJP leader said the Bihar electorate were angry before the 2015 Assembly polls by an in-house remark that “reservation must be debated by those in favour and against”. Lalu Prasad Yadav had weaponised this statement to influence the Yadavs and Other Backward Classes (OBCs), the leader said. “Given all this, the Centre must cautiously tread on the reservation issue.”

Also read: Supreme Court’s flawed verdict on Maratha quota shows why factoring caste history is crucial

Temporary political gain in Maharashtra?

Since politics varies from state to state, the BJP that is in opposition in Maharashtra is now trying to turn the table on the Thackeray government. They want to corner the state government for not providing a strong argument in favour of the Maratha reservation.

BJP leader Kirit Somaiya told ThePrint: “The Uddhav government failed to present the whole report on the 2018 Act before the apex court. This resulted in the court wrongly interpreting the issue. How can the state not put forward its case strongly? The Centre has argued that Article 102 does not curb the state’s power to list backward castes for reservation.”

Another leader added: “Uddhav has jeopardised the interest of the Maratha community which is the backbone of his alliance partner NCP. We shall start our agitation on this.”

The Marathas constitute 32 per cent of the population and is a politically dominant class. They wield influence in agriculture, the sugar industry and education. Out of 18 chief ministers, 12 were from the Maratha community. In the present 182-MLA House, 60 per cent are Marathas.

The BJP camp hopes to exploit the deep divide between the rich and the poor in the Marathwada region. The complexities of the reservation issue can also polarise the OBCs against the Marathas in the party’s favour, the leader said.

What is option before the Centre now?

Rather than wade in politically, the Centre would prefer the court to throw up solutions in other states. There are many PILs pending to quash reservations above the 50 per cent limit. Several states want the Centre to request the Supreme Court to form a larger Bench for these PILs.

Seven states had brought law to introduce reservation above the 50 per cent limit. Except Tamil Nadu (69 per cent) and Andhra Pradesh (66 per cent), the other reservations were struck down by courts.

It now depends on the outcome of the Centre’s review petition for states to introduce reservation above the mandated quota.

BJP Rajya Sabha MP Sushil Modi has argued that the apex court judgment has “created a piquant Constitutional and federal crisis. The state’s power has been withdrawn”.

He added: “The majority judgment fails to appreciate that Article 15 empowers the state to identify SEBC citizens and this power has not been challenged by the 102nd amendment. If the review petition fails to convince the Supreme Court, the central government will have to expeditiously bring a Constitutional amendment to resolve the crisis”.

A central minister told ThePrint: “It all depends on how things move in the Supreme Court. We have requested court to correct anomalies. The second option only arises after the first is exhausted. A Constitutional amendment, however, does not restrict state power in choosing a backward community for reservation.”

Also read: SC fair to strike down Maratha quota law. Left to politicians, reservation would become meaningless