New Delhi: Seventy-two years ago, just after India and Pakistan got their independence, the month of October 1947 witnessed massive diplomatic and military activity in New Delhi, Karachi (then capital of Pakistan) and Srinagar, the summer capital of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir.

Both India and Pakistan were angling to assimilate Jammu and Kashmir into their respective territories, but Maharaja Hari Singh, the Hindu ruler of the Muslim-majority princely state, was not committing to either side. At the same time, there were anti-Maharaja protests, primarily in Poonch and Srinagar.

Standstill agreement

The Indian Independence Act of 1947 had put forth the legal basis for the departure of the British from the subcontinent, and guaranteed Partition. To make the transfer of power smooth, a standstill agreement was formulated on 3 June 1947 by the British Indian government, so that “all the administrative arrangements that existed between the British crown and the princely state would continue unaltered between the signatory dominions (India and Pakistan) and the state, until new arrangements were made”.

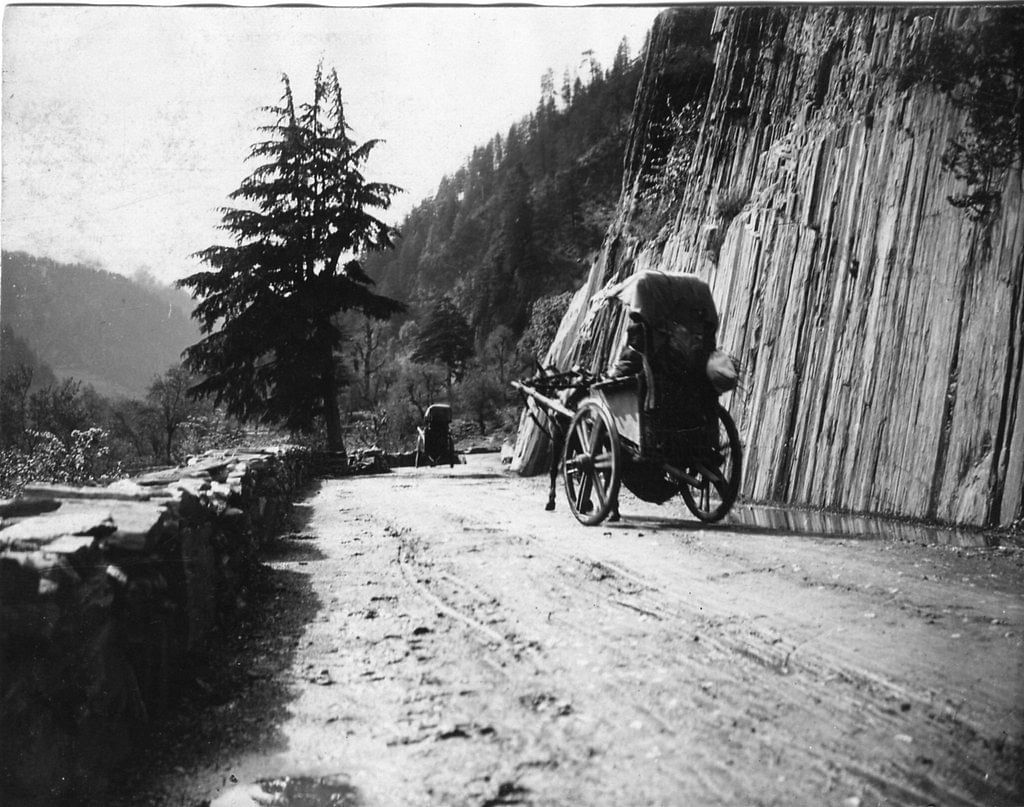

Geographically, Jammu and Kashmir was closer to the areas that would become part of Pakistan — western Punjab and the North-West Frontier Province. It had multiple transient points, such as the only railway line connecting to Jammu via Sialkot, the Sialkot-Jammu road and the Srinagar-Muzaffarabad Jhelum Valley road, through which most of the trade in petrol, kerosene, flour, sugar etc. took place.

On 12 August 1947, J&K sought a standstill agreement with both India and Pakistan, stating: “Jammu and Kashmir government would welcome standstill agreement with Union of India/Pakistan on all matters on which there exists arrangements with the outgoing British India government.”

Pakistan accepted the offer and sent a communication to J&K prime minister Janak Singh on 15 August 1947.

India, however, refused to sign the agreement, instead asking the Maharaja to send his representative to Delhi for further discussions. “Government of India would be glad if you or some other minister duly authorised in this behalf could fly to Delhi for negotiating Standstill Agreement between Kashmir Government and India dominion. Early action desirable to maintain intact existing agreements and administrative arrangements,” it stated, according to. But no J&K representative visited Delhi for negotiations.

The Dogras and Sheikh Abdullah

The princely state of J&K had been brought under British paramountcy in 1846 via the Treaty of Amritsar, signed between the East India Company and Maharaja Gulab Singh, the founder of the royal Dogra dynasty, who paid 7.5 million Nanakshahi rupees and bought the Kashmir Valley and the Ladakh Wizarat (comprising Baltistan, Kargil and Leh), and added it to Jammu, which was already under his rule. Gilgit Wizarat (including Gilgit and Pamiri areas) was conquered later in the war through the Dogras’ war against the Sikhs.

Dogra kings ruled the state of Jammu and Kashmir with an iron fist, with Muslim subjects having fewer rights than Hindus.

Kashmiri author P.N. Bazaz wrote in the book Inside Kashmir: “Speaking generally and from the bourgeois point of view, the Dogra rule has been a Hindu Raj. Muslims have not been treated fairly, by which I mean as fairly as the Hindus. Firstly, because, contrary to all professions of treating all classes equally, it must be candidly admitted that Muslims were dealt with harshly in certain respects only because they were Muslims.”

There were multiple uprisings against the Dogras, mostly notably in 1865, 1924 and 1931.

But after 1931, there was a major shift in the anti-establishment sentiment, headed by a small group of Left-wing Muslim intellectuals under the name of the Reading Room Party, which was a precursor to Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah’s Muslim Conference, which in turn would go on to become the National Conference, according to Birth of a Tragedy 1947 by Alastair Lamb.

Abdullah’s movement for better governance and his mass appeal made him an easy target for the Maharaja, who got him arrested repeatedly between 1931 and 1947.

Also read: Pakistan’s desperation will keep Kashmir simmering as a diplomatic challenge for India

The accession issue

The British departure from India had two major impacts on Jammu and Kashmir.

One, the Maharaja had lost his guarantor, the British, who could not come to his aid to quell any uprising or aggression, as had happened in 1931.

Two, Hari Singh could not keep an eye on the porous border of Kashmir in case of any external aggression.

In his book United States of India and Pakistan, William Norman Brown labels the Maharaja’s position after 15 August as “precarious”.

“He disliked becoming part of India, which was being democratised, or Pakistan, which was Muslim… He thought of independence,” Brown writes.

There was huge pressure on the Maharaja because of the anti-establishment sentiment among the people, fuelled by the fact that Sheikh Abdullah was behind bars, despite repeated requests by Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel and the Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, to release him.

Meanwhile, the fact that J&K’s standstill agreement with India was in limbo was interpreted by Pakistan to mean that the state would eventually accede to Pakistan.

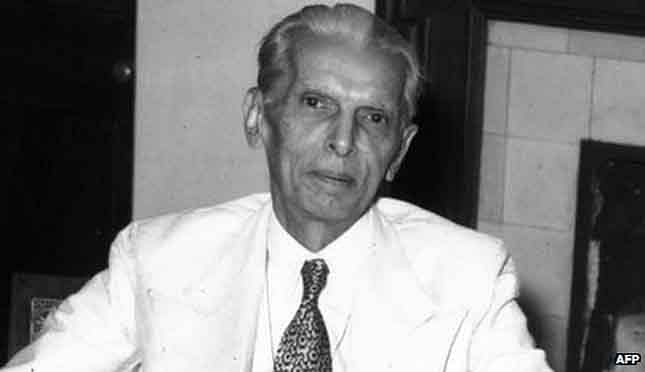

Pakistan Governor General Mohammad Ali Jinnah sent his private secretary Khurshid Hasan Khurshid to Srinagar to assure the Maharaja about signing an instrument of accession with Pakistan. “His highness was told that he is a sovereign that alone has power to give accession; that he need consult nobody; that he should not care about Sheikh Abdullah or National Conference…” Jinnah’s letter, handed over by Khurshid to the Maharaja, states.

However, within 12 days of signing the standstill agreement with Jammu and Kashmir, Pakistan wrote a warning note to the Maharaja, on 24 August: “The time has come for Maharaja of Kashmir that he must take his choice and choose Pakistan. Should Kashmir fail to join Pakistan, the gravest possible trouble will inevitably ensue.”

This warning alarmed the Maharaja, and charges and counter-charges were exchanged between Pakistan and J&K.

On the other hand, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi wanted Kashmir to join India. Nehru’s Kashmiri roots and friendship with Sheikh Abdullah made him push for it. However, because of the complications with Hyderabad, which wanted to join Pakistan, the government’s focus was on the Nizam.

According to historian Rajmohan Gandhi: “Vallabhbhai (Patel)’s lukewarmness about Kashmir had lasted until September 13, 1947.” In a letter that morning to Baldev Singh, India’s first defence minister, Patel had indicated that ‘if (Kashmir) decides to join the other Dominion”, he would accept the fact.

The tribal invasion

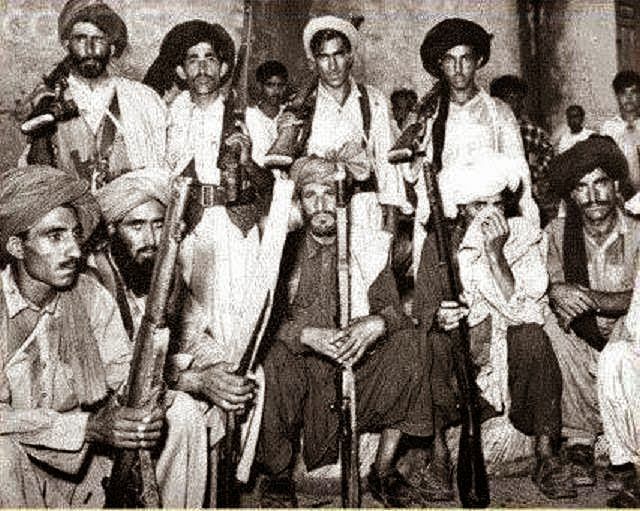

In June 1947, about 60,000 ex-army men (mostly from Poonch) had started a no-tax campaign against the Maharaja. The campaign later turned into a secessionist movement following 14 and 15 August, when Poonch Muslims hoisted Pakistani flags. The Maharaja imposed martial law in Poonch, which further angered the Muslims there. With ammunition and personal support provided by the tribals of Pakistan’s NWFP, the situation got more complex, according to Victoria Schofield’s book Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War.

On 4 September 1947, General Henry Lawrence Scott, commander of the Jammu and Kashmir state forces, complained about multiple covert incursions from Pakistan and asked the Maharaja’s government to raise this issue with Pakistan. The same day, the J&K PM Janak Singh officially complained to Pakistan and asked for “prompt actions”.

Meanwhile, Pakistan also levelled similar charges on the Jammu and Kashmir administration, about incursions by Jammu Hindus into Sialkot.

Weary of all this, Maharaja Hari Singh released Sheikh Abdullah, who, in his first very first public meeting, reiterated that “the demand of the Kashmiri is freedom”. He also took a jibe at Jinnah, saying: “How can Mr Jinnah or the Muslim League tell us to accede to Pakistan? They have always opposed us in every struggle. Even in our present struggle (Quit Kashmir), he (Jinnah) carried on propaganda against us and went on saying that there is no struggle of any kind in the state. He even called us goondas.”

In early October, the Maharaja complained to Pakistan’s foreign ministry about the infiltration by tribals hundreds of kilometres inside the border in the Jammu region. Pakistan denied the allegation, but called the Maharaja’s attention to “terror and atrocities perpetrated by J&K forces against the Muslim population of Poonch” — atrocities which, it suggested, were provoking “spontaneous reactions both within J&K and from ethnic and religious kin across the border”.

Not much is known about the violence in Jammu and Poonch at this time, except for a couple of reports in British publications The Times and The Spectator. The Times stated: “2,37,000 Muslims were systematically exterminated — unless they escaped to Pakistan along the border — by the forces of the Dogra State headed by the Maharaja in person and aided by Hindus and Sikhs.”

A young lawyer and landowner from Poonch, Sardar Ibrahim Khan, a member of the Jammu & Kashmir Legislature who had been a legal officer under the Maharaja, emerged as the head of the Poonch liberation movement. He united the different factions in Poonch and held contact with some of the key figures of Pakistan’s Muslim League, including prime minister Liaquat Ali Khan. He was instrumental in establishing an “Azad Kashmir” government in Rawalpindi.

As relations froze, Pakistan suspected that Maharaja Hari Singh would accede to India. Also, given Sheikh Abdullah’s animosity towards the Muslim League, Pakistan took the decision to seize Kashmir by force. Due to the geo-strategic location of the state, Pakistan feared that if Kashmir went to India, Pakistan would cease to be militarily and politically viable. According to an academic paper titled ‘India-Pakistan Relation Past Present and Future’ by Dr Sanjay Kumar, Pakistan brigadier-in-charge in Kashmir Major General Akbar Khan said: “Kashmir’s accession to Pakistan was not simply a matter of desirability but of absolute necessity for its separate existence.”

Also read: Bakarwal nomads return to the plains as business dries up due to Kashmir shutdown

‘Operation Gulmarg’

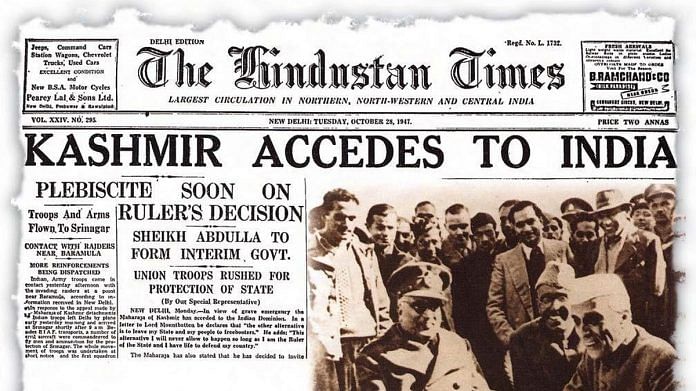

Pakistan launched ‘Operation Gulmarg’ by mobilising tribals from the NWFP on 22 October 1947. About 2,000 tribesmen, fully armed with modern weapons and under the direct control of Pakistan Army generals, entered Muzaffarabad in motor-buses and on foot.

As the invaders captured Uri and Baramulla with minimal resistance from the Maharaja’s forces, the fall of Srinagar looked imminent. On 24 October, Maharaja Hari Singh appealed to India for military assistance to stop the aggression.

The request was considered on 25 October in a meeting of India’s Defence Committee, headed by Mountbatten and including Nehru, Patel, Baldev Singh, minister without portfolio Gopalaswami Ayyangar, and the British commanders-in-chief of the army, air force and navy. The committee concluded that “the most immediate necessity was to rush arms and ammunition already requested by the Kashmir government, which would enable the local populace in Srinagar to put up some defence against the raiders”, according to Lt Gen. K.K. Nanda’s book War with No Gains.

However, according to Jyoti Bhusan Das Gupta’s book Jammu and Kashmir, Mountbatten warned that “it would be dangerous to send in any troops unless Kashmir had first offered to accede”, arguing that it would result in an India-Pakistan war. He suggested the accession should be considered as provisional, and “when law and order had been re-established in Kashmir, a plebiscite should be held as regards Kashmir’s future”.

The Defence Committee sent V.P. Menon, secretary of the Ministry of the States, to Srinagar to “make an on-the-spot study” the same day. He returned to New Delhi the next day with his impressions, and suggested sending troops to Kashmir, pointing out the “supreme necessity to save Kashmir from raiders”.

In the meantime, the new prime minister of J&K, Mehr Chand Mahajan, warned: “We have decided by 25th evening to go to India if we get a plane or else to Pakistan to surrender.”

Menon was then flown to Jammu to advise the Maharaja about the government’s view, and that’s when the Maharaja finally signed the Instrument of Accession on 26 October, and Menon returned to Delhi with Mahajan.

The Instrument of Accession

The Instrument of Accession guaranteed limited access to India in Jammu and Kashmir—on matters of defence, communications and foreign affairs.

• In Clause 4, the Maharaja declared the accession of the state to India.

• Clause 5 declared that terms of the instrument were invariable, and cannot be changed by amending any law/act etc. without the acceptance of the J&K legislature by a supplementary instrument.

• Clause 6 declared that the Union of India didn’t have any power to make laws in the state in terms of land acquisition, and also specifically mentioned the Union could not purchase land in Jammu and Kashmir, unless the law demanded so.

• Clause 7 enumerated that the Maharaja didn’t have to accept the future Indian Constitution and the government of India could not force the Maharaja to do so.

• Clause 8 stated in clear terms that “nothing in this instrument affects the sovereignty” of Maharaja, while Clause 9 made it explicitly clear that he was signing that document on behalf of the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Therefore, it is clear that the government of India had acknowledged the Maharaja as a legal representative of the people of Jammu and Kashmir.

Aftermath

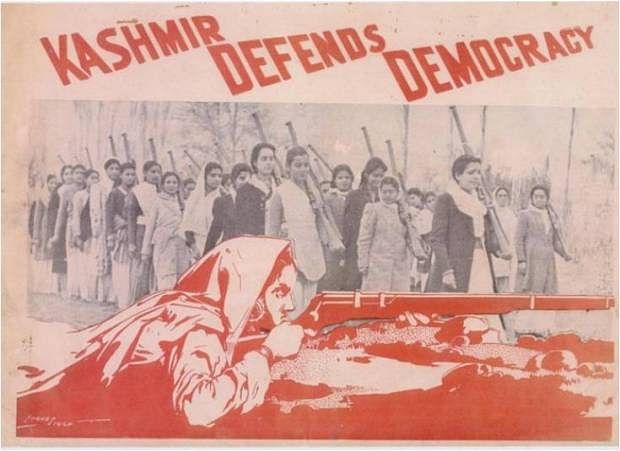

The Indian Army was finally airlifted to Srinagar to repel the tribal invasion. Militias recruited by Sheikh Abdullah were trained by the army.

On 1 January 1948, Nehru formally took the Jammu and Kashmir issue to the United Nations Security Council (‘India-Pakistan; the History of Unsolved Conflicts’ by M. Ahmad Mir).

During the course of 1948, Pakistan claimed the war in Jammu and Kashmir was between the Indian Army and the “soldiers of Azad Kashmir”. By May 1948, the Indian Army was prevailing in the fighting, and making gains towards the Poonch-West Punjab border. Pakistan then openly mobilised its troops to assist the “Azad Kashmir Army”.

On 13 August 1948, the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan passed a resolution providing for a ceasefire; the withdrawal of Pakistani troops and tribal militia, followed by an Indian withdrawal; and a plebiscite.

However, following the ceasefire, neither side pulled back their armies, and the plebiscite never took place.

Also read: New study predicts impact of India-Pakistan nuclear war — over 100 million dead

We Kashmir Never Accpet india or pakistain ..

We kashmir Consider India or pakistain Is not a party of Our kashmiri nation

Dont Dream For Bothside

We kashmiri N=know How to defen and development our JK Nation From Terissim

A very good article capturing the facts of those times. Few important facts to note.

1) Pakistan seeing Kashmir as an issue of defense and strategic geopolitical advantages.

2) Pakistan’s attempt to compel the Maharaja to accede and denouncing the popular leader Sheikh Abdullah reflects Pakistani imperialism.

3) Pakistan never cared for people but only for land and unfortunately it is still the case after decades. Iron fist approach and Oppression of minorities including Muslim minorities such as Shia, Ahmedia, Baloch etc. reflecting the ideology of Pakistani leaders.

4) Unfortunately, Pundit Nehru was largely blamed in India for current Kashmiri crisis, these facts are an eye opener for Indians.

5) Sir Mount Batton, Nehru and Gandhi had one thing in common, they respected Kashmiri people, their beliefs and their representative Sheikh Abdullah. They had the choice of compelling the Hindu Maharaja but the chose Secular and Democratic values over other material advantages.

6) India insisted and demanded the release of Sheikh Abdullah.

7) Dogras ruled the region with iron fist and oppressed Muslims similar to any other Muslim rulers who oppressed majority Hindus in rest of India. It’s not religion but rulers using religion are their instrument to control the people.

8) Kashmiri crisis is very complex and tactics applied by all parties involved, made it even worse.

9) Abolition of Article 370 may not be inline with the clauses of Accession but the clauses on Accession only implies the sovereignty of the Maharaja not the people of Kashmir, but India made sure Article 370 represents Kashmiri Assembly as the Government instead of the Maharaja (or may be crown prince).

10) The Article 370 delivered no value to a common Kashmiri but prevented any economic growth in the region by limiting access to the Union Government.

11) Given the facts and as Mahatma Gandhi envisioned, India is the Testimony that Jinnah was fundamentally wrong and secular country can always be better than an Islamic/Hindu nation.

Those who are questioning the abrogation of article 370.which was temporary, should also answer that the Privilege Purses agreed to the princes of former state rulers at the of singining of instruments of acceccesion with government of India. And these were not temporary. Why these purses were withdrawn by Indira. Was not this act too illegal?

The Instrument of Accession signed by the Maharaja with its own unique clauses was thought to be an all but temporary agreement between J&K and India but just as other princely states namely, Hyderabad and Travancore had their own clauses which were included in their Instruments of Accession which in due course got diluted and these princely states completely adhered to the constitution of India so does the J&K accession clauses too. In this sense, the present revocation of Article 370 is exactly under the Constitution of India and it is high time Kashmiris accepted the fact that they are legitimate citizens of India and disown the external influences indoctrinating them and strive to lead a peaceful and successful life. The whole Indian nation will support them in this regards.

Excellent primer. The crux of this problem lies in identifying whether it is a territorial issue or an ethnicity issue. India is not ambiguous about it and treats it as former. It is Pakistan that is playing fuzzy, and therefore the solution needs to come from Pakistan. It should withdraw all its troops from PoK, and let PoK issue visas to Indians as an independent, sovereign nation, allowing them to visit the beautiful Gilgit-Baltistan areas. Once that happens, India will be compelled to let Kashmir valley merge with the TRULY AZAD KASHMIR. Till then India is doing what every government in the world does – protect its territory by putting boots on the ground.

The complex history of the state – part of it enumerated so well in this column – requires that it be dealt with with a light touch, not a battering ram.

Independence act of 1947 isnt independent of GOI Act 1935.

Kashmir agitation led by kashmiri muslims of kashmir was against Hindu Maharaja nit against establishment per se.

Present imbroglio is based on same .to honour the seperatehood of kashmiri muslim hegemony and majoratarionism.

The aetucle is bringing out selective references of the events to push a pro kashmiri muslim narrative thus undermining the sovereignty and integrity of Secular democratic India.

India cant allow a de facto muslim state to run onthe soil of secular democratic India.

It needs to be demolushed.