It was around this time that Dr Ambedkar’s deification began. Mahar sadhus, or ascetics, of different sects (Kabirpanth, Nathpanth, etc.) had been brought together by one of Ambedkar’s associates who sought to prevail upon them to actively engage in social work, rather than just wander around begging from the community. At first, they agreed that they would spread awareness about the Mahad Satyagraha. But then a bizarre debate erupted between them, consuming all of their focus and attention. Dr Ambedkar, most certainly, was an avatar of God—but which god? One sadhu asserted that Ambedkar was obviously Rudra, since they had the same demeanour. But another countered that Rudra could not manifest in full form into the body of an untouchable. After an animated debate, consensus slowly emerged that Ambedkar was an incarnation of half-Rudra, although a couple of sadhus remained unsatisfied even with this cunning solution. Later, when all of this was recounted to Ambedkar, at first he burst out laughing at the absurdity of it. But then his face changed and he grew serious, telling everyone around him that it was with baroque theological preoccupations such as this that Brahmans had poisoned the Indian mind.

A crowded photo of Ambedkar with the volunteers of the Samata Sainik Dal taken in 1928 is perhaps evidence of at least one of the benefits of his metamorphosis into a mortal god in the eyes of many in his community. The picture shows some 400 sainiks, looking disciplined and remarkably well organized. He would have no trouble recruiting manpower for any of his future pursuits. Still, Ambedkar had little patience with being worshipped. He was not a humble man, but he was the furthest thing from egotistical or in need of flattery. Above all, he was rational, practical and earnest—qualities at complete odds with being regarded as divine.

The futility of it aggravated Ambedkar, who felt, and often bluntly told his worshippers, that it would be far better if they sloughed off their slavish mentality and even their belief in gods, and focused, instead, on social work for others and on their own self-respect.

Throughout Ambedkar’s life, for the entire time that he was Hindu, his thoughts and actions on various aspects of religion and spirituality remained indecisive and even ambiguous. It was only after Ambedkar had become sure that he would convert to Buddhism, something that seems to have crystallized for him right around 1947-48, that his variegated views on religion, and spiritual thought and practice became much more clear, decisive and confident—although still not fully consistent until around the official conversion itself, another eight or nine years further along.

In 1948, Ambedkar published a unique and fascinating book polemically exploring the origins of untouchability in ancient India, intimately interlacing those origins with the religious and social struggle between Hinduism and Buddhism. He dedicated that book to the untouchable saint Chokhamela (as well as Nandanar and Ravidas), indicating that by that time, Ambedkar had become fully at ease with acknowledging the positive religious and even social contribution that saint-poets such as Chokhamela had made. But that was twenty years ahead in time from what we are discussing now. In January 1928, a meeting of the depressed classes was held in Trimbak, a town near Nashik, where the Trimbakeshwar Shiva temple is located. The meeting was convened to contemplate the ways and means to construct a temple to Chokhamela for use by the untouchables. Ambedkar was asked to preside—a clear strategic mistake on the part of those who sought to build the temple. Ambedkar prevailed upon the group to forego building the temple, arguing that it would be a far more apt memorial to this great saint to use their resources of time, money and energy towards social causes instead. At this period in his life, Ambedkar could not actually see that untouchable saints such as Chokhamela had contributed anything substantial to the social sphere, despite their eloquent advocacy for the equality of all devotees. He was reading all of the available literature on the Bhakti Movement, on Chokhamela, on Tukaram, on Dnyaneshwar and about his father’s own Kabirpanth tradition—his obsessive book-collecting had by no means ebbed in late 1920s’ Bombay—and across all of these various devotion-based movements, he could discern only the advocacy of equality of believers, as opposed to the more radical and relevant demand of social equality as such. It was also not lost upon him how easily any such Hindu-based spiritual movement, howsoever egalitarian, could be assimilated into the overpowering paradigm of Brahmanical Hinduism, thus working against social emancipation instead of towards it.

This latter threat loomed large in Ambedkar’s mind throughout this era, where temple-entry satyagrahas were taking centre stage, even dislodging the unambiguously civil-rights-based struggle for untouchables’ equal access to public water sources, exemplified by Mahad. The status of temples as public-versus-private was always more opaque an issue than that of water sources, schools or roads. And the British government was generally averse to interfering in religious matters unless they could see a practical benefit to themselves. Constantly weighing heavy on Ambedkar’s mind, too, was just how viciously violent temple-entry campaigns always were. Hindus never shied away from spilling blood when it came to upholding the ‘purity’ of their temples. The Parvati temple satyagraha in Pune in October 1929 was a good example of this.

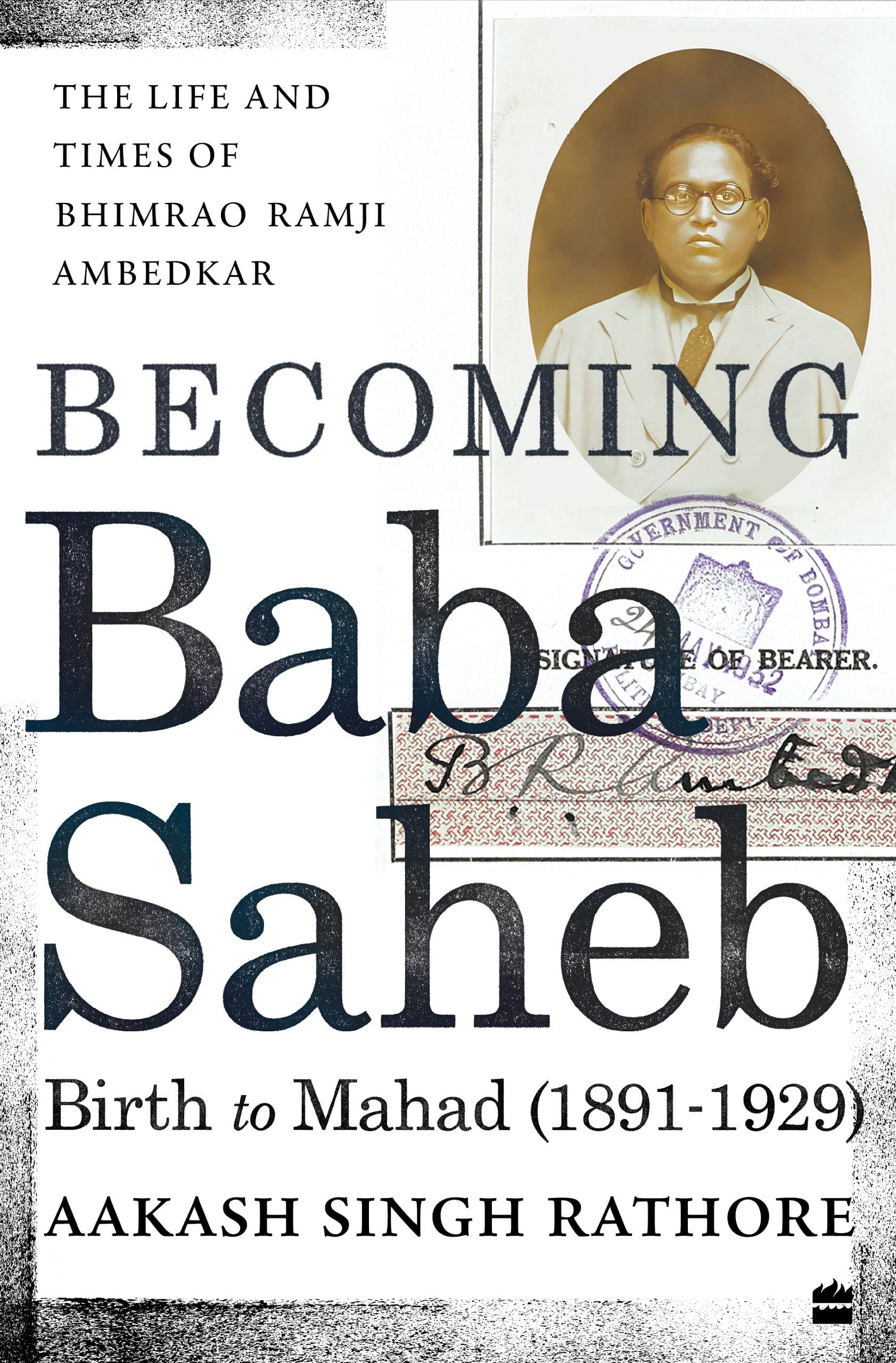

This excerpt from Becoming Babasaheb: The Life and Times of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (Volume I) by Aakash Singh Rathore has been published with permission from Harper Collins India.

This excerpt from Becoming Babasaheb: The Life and Times of Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar (Volume I) by Aakash Singh Rathore has been published with permission from Harper Collins India.