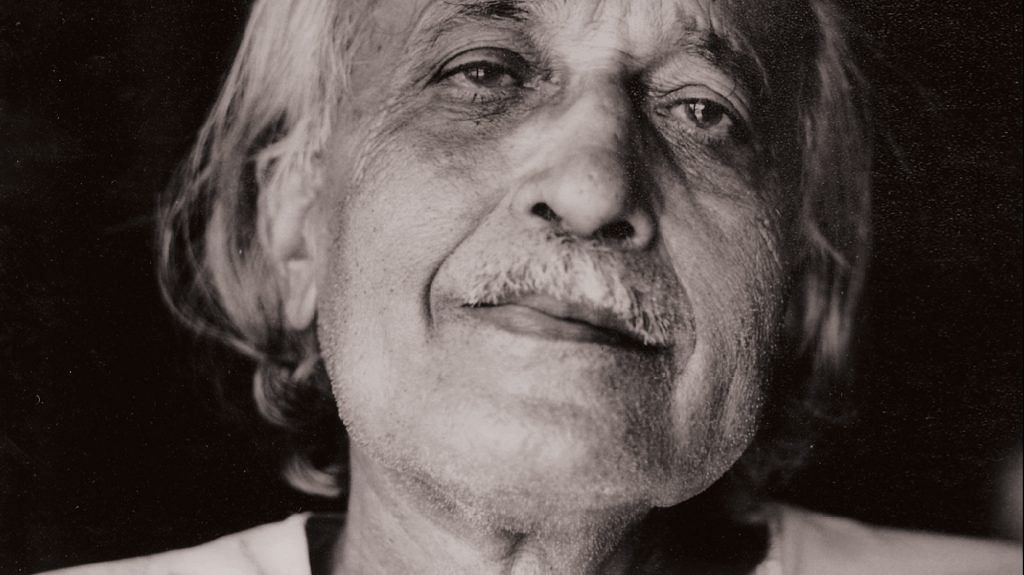

Tata inspired hundreds of talented men and women in the generations that followed him. Much has been written about him by many of them. My focus here is on a few such individuals whom I personally got to know well in later years.

Prabhashankar Rao Padukone (1923-2014, Ramananda Rao’s son, Tata’s old mentor, got to know Tata well. He was a boy during the days Tata stayed in their home. He was a widely read man, deeply interested in music, both Indian and western classical. Padukone was also a well-known Kannada humorist. His collection of essays, Telibanda Yelegalu (Leaves That Floated By) contains some very touching accounts of how Tata mentored him. I was fortunate to hang out with him in New York City for a few days in 1989 when Padukone was chaperoning Tata around. His wife, Vrinda Padukone (née Mundkur), was a childhood friend of Amma’s. Of the same vintage was H.Y. Sharada Prasad (1924-2008), a firebrand student leader in Mysore during the 1942 Quit India movement. He was a Nehruvian idealist who later became an official in the inner circles of the Nehru–Gandhi dynasty. Sharada Prasad admired Tata greatly. Tata was very fond of him and his wife Kamalamma, and stayed in their official residence near Lodi Gardens when he was in Delhi. Later, when I visited Delhi for work, their home became my refuge too. Although Tata was vehemently opposed to Indira Gandhi, his friendship with Sharada Prasad, who was her key advisor, never frayed.

Also read: Hindi Diwas sees big protests by pro-Kannada groups, politicians & film stars also join in

In one instance, when Tata took Sharada Prasad’s two boys, Ravi and Sanjeeva, for a walk in the Lodi Gardens, a perfect stranger stopped them and asked Tata if the boys were his grandchildren. Without batting an eye, Tata had replied, ‘No, but they are indeed grand children!’ Another eminent cultural figure who was similarly inspired by Tata was the Ramon Magsaysay Award winner, K.V. Subbanna (1932-2005). His contributions to Kannada literature, theatre and the performing arts, all the while based in the little village of Heggodu deep in the Western Ghats, are well-known. Subbanna was a rationalist like Tata, but unlike Tata, he was also a socialist. However, their shared interests and bonds of affection ensured that these ideological differences mattered little. I remember Subbanna’s visits to Puttur during my school days. I have visited Heggodu with Tata in my boyhood and have continued that tradition over the years to watch with admiration how Subbanna’s son (and my friend), K.V. Akshara, is expanding his father’s cultural quests in multiple dimensions.

Tata was also an inspiration to three other next-generation stars of Kannada literature, theatre and culture: U.R. Ananthamurthy, Girish Karnad and B.V. Karanth. It was only after I got to know them well later that I realised how profound Tata’s influence had been on them during their formative years. And how much they stood in genuine awe of Tata’s pioneering intellectual and personal explorations despite their ideological differences with him.

Among the trio, Tata was personally very fond of Ananthamurthy (1932-2014). When Tata was in Mysore, he would always drop in for a cup of coffee with Murthy. Basking in Tata’s reflected glory, Prathibha and I too have benefited much from Ananthamurthy’s incredible affection and charming erudition. Although B.V. Karanth made a brilliant film based on Tata’s famous novel Chomana Dudi, Tata had not liked the film. B.V. Karanth, a warm, good-hearted man and a true genius of Kannada theatre, in contrast to Tata, was somewhat undisciplined and often unpunctual. I suspect Tata’s dislike of that outstanding movie had more to do with B.V. Karanth’s disorganised persona. B.V. Karanth had once confessed to me that he was ‘scared of’ Tata.

Because Tata was a jack of all trades who dabbled in anything that took his fancy, some of his prolific intellectual output tended to be mediocre. Since Tata did not like B.V. Karanth’s film, he set out to make a better movie based on another acclaimed novel of his, Kudiyara Koosu. Prathibha and I spent a couple of days on the sets when this movie, titled Maleya Makkalu, was filmed in a very scenic forested landscape in the Western Ghats. Although the scenery was grand and the movie starred the popular Kannada actress Kalpana, the movie was a rather amateurish effort compared to Chomana Dudi. Tata’s film failed the test of critical appreciation, and at the box office. Another writer of the Ananthamurthy–Karnad–Karanth generation was poet K.V. Puttappa’s (Kuvempu) son Poornachandra Tejaswi (1938-2007). He was a leading Kannada writer who genuinely shared Tata’s wider interests in nature and photography.

Because of my own interest in the same topics, I got to know Tejaswi fairly well in the 1980s. Tata met him a few years later, and from the word go, they got along really well. Tejasvi later told me it was his eternal regret that he did not reach out and get to know Tata much earlier. Tata’s wide range of interests, passion and frankness had greatly impressed Tejaswi.

Also read: Alur Venkata Rao — one of the first Kannadigas who gave a call for unified Karnataka

Kannada pride and cultural connections

The South Kanara that Tata grew up in was a part of the Madras Presidency. The present-day Karnataka region had been historically fragmented and administered separately by various powers. Under colonial rule, the Kannada-speaking regions were partitioned among the presidencies of Madras and Bombay and the colonially supervised princely states of Hyderabad under the Nizam and Mysore under the Wodeyars. In all these units, except Mysore, the Kannada language was suppressed and Kannadigas were discriminated against in educational and employment opportunities. Consequently, there was a deep groundswell across the entire region to unify all Kannada-speaking people through ‘Karnataka Ekikarana’ (unification).

The idea of Ekikarana took birth in the mid-nineteenth century, building on the foundations laid by pioneers like ‘Deputy’ Channabasappa, Ra. Ha. Deshpande and other passionate men. The superstructure of the movement rose in the early twentieth century. The spirit of Karnataka Ekikarana was captured emotively by Huilgol Narayana Rao’s aspirational song titled ‘Udayavagali Namma Cheluva Kannada Nadu’ (may our beautiful Kannada land rise again). It was sung melodiously at the Congress party’s 39th national session at Belagavi (1924), presided over by Mahatma Gandhi. The singer was an eleven-year-old schoolgirl, Gangubai Hangal, who later attained legendary fame as a Hindustani vocalist.

Tata’s love for Kannada drew inspiration from senior leaders of the Ekikarana movement like Mudaveedu Krishna Rao and Aluru Venkata Rao. Tata and his brother K.R. Karanth were both drawn into the Karnataka Ekikarana movement even before the 1930s. I think Tata’s elder brother saw it as a movement for political and economic emancipation of Kannadigas, while Tata felt strongly about the cultural subjugation that Kannadigas faced, under the state-sponsored dominance of the Tamil, Marathi and Urdu linguistic minorities in all regions except the princely state of Mysore.

After Independence, K.R. Karanth was a prominent leader of the Ekikarana movement, along with his contemporaries like Ranga Rao Diwakar (a member of Jawaharlal Nehru’s cabinet in Delhi). Tata aggressively canvassed for the idea of Ekikarana within his own

literary and cultural domains. Tata’s pride in Kannada was not merely of the parochial kind, content to rejoice in the past glories of Karnataka. Tata was a true modernist who saw and appreciated the progress that could be achieved through science, technology and economic development. His intense belief was that Kannadigas could not be a part of such overall progress without their linguistic and cultural emancipation. Tata’s views on the unification of Karnataka were at odds with some writers of the princely Mysore state whose loyalty to the king dampened their enthusiasm for the unification. As a little boy, I witnessed the Kannada Sahitya Sammelana at Mysore in 1955, which Tata had presided over. He spoke eloquently in favour of Ekikarana to thunderous applause from Kannadigas from all over the region, muting any discordant voices.

The popular struggle for Ekikarana finally bore fruit in 1956 with the formation of the greater Mysore State (comprising of princely Mysore and other Kannada-speaking regions) which was later renamed Karnataka in 1973. The movement has been documented in several accounts, with H.S. Gopala Rao’s scholarly work being the most comprehensive.

An important segment in Tata’s intellectual quest was his deep interest in the popularisation of science. It was driven by a desire to make new knowledge readily accessible to Kannadigas. For him the love of Kannada and Karnataka was not just about marching in the streets, shouting slogans and glorifying the past. It was about working hard now to ensure the best ideas and things in the world reached Kannadigas most effectively.