The role of the midday meal and other incentivization programmes in enhancing GER and helping arrest dropout rates is now accepted wisdom. But it also had another benefit– it bridged the gap between the GERs for girls and boys. It also brought in those who were least likely to attend school –girls from poor and backward regions and from marginalized sections of society.

Dropout rates for girls are higher than for boys at all levels all across India, except in Kerala. Unsurprisingly, therefore, female literacy lags behind male literacy. Keeping girls in school, however, is the greatest force multiplier for improving development outcomes. Education among girls is the most significant variable correlated with low fertility rates worldwide. It also results in a higher female labour force participation rate (LFPR).

Moreover, if and when an educated girl does become a parent, her own children will almost certainly be as educated as she is. It produces a virtuous cycle of fewer newborns, who have access to better basic health services, better education and higher per capita income.

When M.G. Ramachandran relaunched the midday meal scheme in Tamil Nadu, he explicitly mentioned provision of nutrition for women and girls as an important consideration when he answered critics who had accused him of spending beyond the state’s means. In a single generation, that policy paid back many times over.

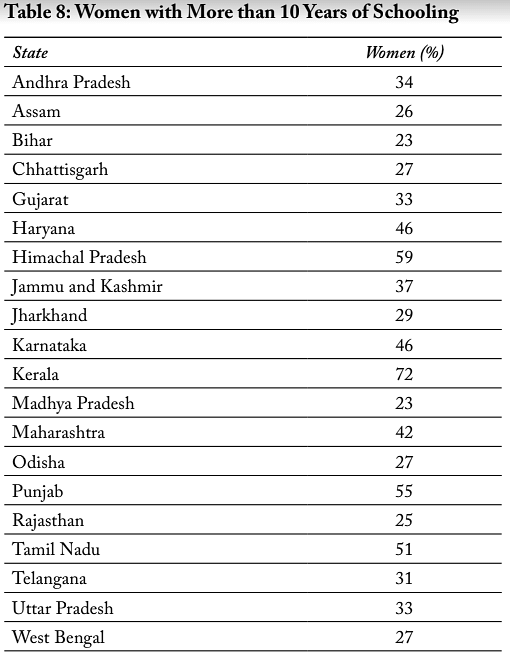

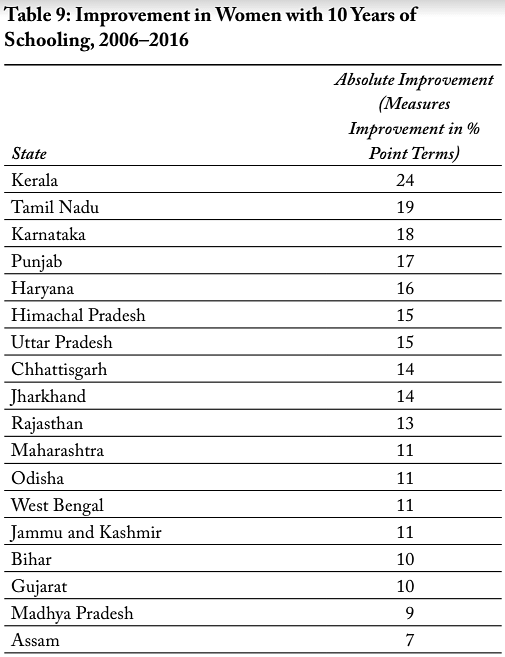

A measure of success in girls’ education – which is a good proxy for education in general – is the percentage of women who received ten or more years of schooling. NFHS-4 data suggests that Kerala leads in this metric, followed by Himachal Pradesh, Punjab and Tamil Nadu (see Table 8). But, as with overall literacy, this metric again measures the number of educated women in the overall population. Younger women making greater progress is a more reliable indicator of more recent gains. So, if we look at the improvements in the percentage of women who had over ten years of schooling between 2006 and 2016, predictably, southern India leads (see Table 9).

An important question for policymakers, given the context, is this: over and beyond the basic midday meal scheme and establishment of a school network that children can access, what makes girls stay in school?

International Institute for Population Sciences, 2017

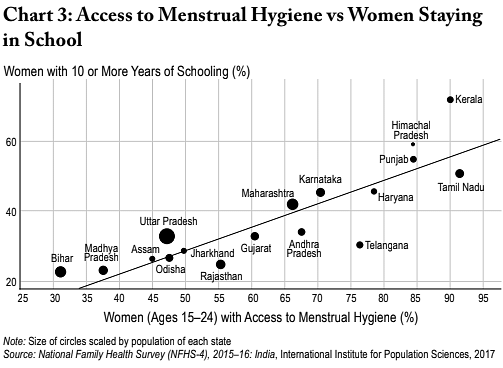

It turns out that girls often drop out of school in the higher secondary stages because of concerns over menstrual hygiene, availability of toilets in school, etc.

International Institute for Population Sciences, 2017

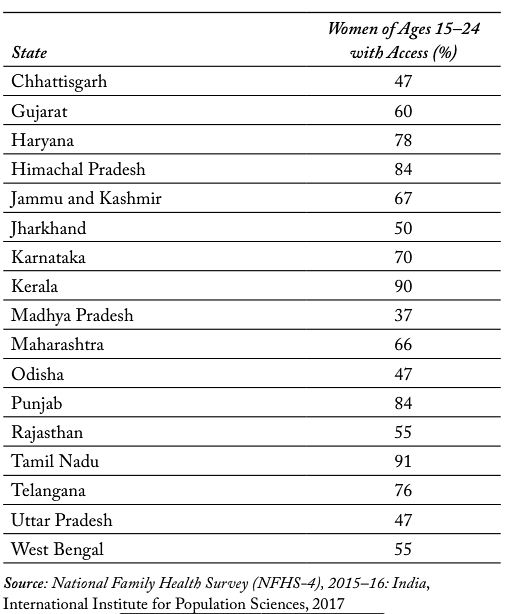

States where girls and women have greater access to menstrual hygiene are, generally, also states where they stay longer in school (Chart 3).

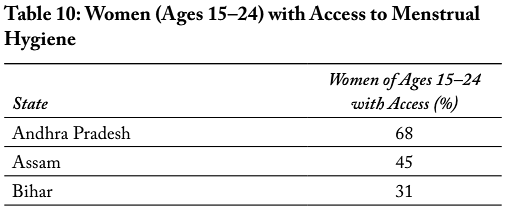

Southern India leads when it comes to the metric of availability and access to menstrual hygiene for women in the 15–24 age group, just as it leads in the improvement in percentage of girls with ten years of schooling (see Table 10). This buttresses its GER in higher secondary education and improvement in literacy of younger populations as well.

International Institute for Population Sciences, 2017

This excerpt from South vs North: ‘India’s Great Divide’ written by Nilakantan RS has been published with permission from Juggernaut.

This excerpt from South vs North: ‘India’s Great Divide’ written by Nilakantan RS has been published with permission from Juggernaut.