Anyone who expressed dissent—even when the grounds of their dissent were valid—were thrown in jail. Countless others were detained without reason. Members of the Jamaat-e-Islami and RSS were arrested. There was a young boy, fifteen years of age, by the name Bhavani Shankarudu. My last writ petition in Emergency cases was filed on his behalf. He later became a leader of the Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh. One day, after arguing a habeas corpus case in the court of Justices Sambasiva Rao and Gangadhara Rao, I came out and lit a cigarette. This was soon after the Supreme Court ruled that the MISA was valid law. Bhavani Shankarudu was produced in court. When the judges asked him who his lawyer was, the young boy said, ‘Kannabiran.’ He must have been instructed to do this in jail. The judges immediately said, ‘Kannabiran has just left the court hall, call him back.’ I went back in. Taking one look at the boy who had not yet grown a moustache, I said to the judges, ‘If the law says that a boy like this poses a threat to internal security, it is a useless law.’ The government pleader stood up and stated to the bench, even before he was asked his opinion, that these detentions should simply be confirmed in light of the Supreme Court judgment in the MISA case, and that there was no need to argue the cases. I turned to him with a repartee, ‘I don’t think you have become a judge yet.’ I would be quick to respond in every situation like this before me in courts. While I was still there, VIRASAM leader K.V. Ramana Reddy was brought to the court. He delivered a good speech which he ended with, ‘Long live even bourgeois democracy.’

This spate of arbitrary and indefinite arrests reduced the families of several detenus to penury. Pattipati Venkateswarlu is an example. He was a young lawyer who was beginning to build a secure practice—how would his family support itself during his incarceration? I called for files pertaining to all the cases Venkateswarlu was handling, and asked his clerk Venkata Rao to inform all his clients that I would be taking care of their briefs. Every client had to first deposit their fees with his wife, Venkataseshamma, and then come to me. Only after she confirmed that she had received the fees would I argue the case in court. This was only one such instance.

Justice Thota Lakshmaiah wrote a long judgment praising the Emergency, perhaps in the hope that by that token he would be elevated to the Supreme Court. Justice T.L.N. Reddy, then a district and sessions judge, wrote a judgment eulogizing the Emergency. What this points to is merely the fact that the intelligentsia that ought to have put social transformation at the forefront supported authoritarianism in pursuit of personal gain instead. This trend was in full public view.

V. Rama Rao, of the Jana Sangh (who later joined the Bharatiya Janata Party [BJP] and served as the governor of Sikkim), is a close friend of mine. He and CPI(M) leader Omkar filed a special writ petition. They were members of the Andhra Pradesh Legislative Council and the Andhra Pradesh Legislative Assembly respectively. ‘Our involvement, as elected representatives, in the work of the Assembly cannot be construed as a threat to internal security. We attend the Assembly sessions to fulfil our public responsibility.’ I argued for two days. It was before the bench of Justice Avula Sambasiva Rao. He asked how they should be sent. The petitioners suggested that they could be sent with an escort and after the session transported back to jail. The petition was struck down.

Advocate M.V. Ramamurthy’s petition was even more unusual. He asserted that he had the right to have intimate relations with his wife. The Emergency had not struck down that right. Therefore, he argued that his right to sexual intimacy must be protected, and he must be permitted to be with his wife at intervals. When he filed this petition he was around sixty years old. He was a humorous person. This petition came before Justice P. Chennakesava Reddy. Vadari Venkataramaiah was the amicus curiae. Although his petition was also dismissed, it generated a lot of debate.

I got acquainted with M.V. Ramamurthy through Emergency cases. Although we had differences of opinion on various matters, he was a very friendly and warm person, and a great conversationalist. The reason why the court struck down the petition was that it saw the right to intimacy as a private right, the protection of which was not the responsibility of the state.

Shaikh Meera, a secondary grade teacher in Bardipur village, Nizamabad district, detained in September 1976 under the MISA, petitioned the court seeking to be classified under Class B, rather than Class C, which was for prisoners, not detenus. The case came up before a bench consisting of Justice Ramachandra Raju and Justice A. Raghuvir. The public prosecutor opposed this on the grounds that in light of the Supreme Court judgment, the actions of the state could not be questioned under the Emergency, and that this matter should be resolved by the petitioner making a representation to the government. The court ruled in favour of Shaikh Meera and held that he should be treated as a detenu in Class B.

Detenus who secured release were rearrested in fresh cases. Jana Sangh leader Burra Subbarayudu was rearrested before he reached home after securing release from the court, and held in the police station. There were no lawyers to represent him. Advocate Babul Reddy, whose name he mentioned, was unwilling to represent him, so I did. In the process of detenus raining petitions on the courts, the latter became places of political assembly. Since it was no longer possible to debate politics outside, courts now became the sites of such debates. People poured into them. As I walked from one court to another, a crowd would follow me. As I kept arguing cases, the case of senior advocate from Guntur, Jupudi Yagna Narayana, was posted before the bench of Justice Chinnappa Reddy and Justice Jeevan Reddy. I had visited him and Gouthu Latchanna in Osmania General Hospital.

When detenus were unwell, they got admitted in hospitals outside. This also gave them an opportunity to meet their family and friends and breathe some fresh air. I had a MISA case hearing that was coming up before the full bench of Justice Kuppuswamy, Justice A.V. Krishna Rao and Justice Ramachandra Raju at the same time that Yagna Narayana’s case was to be heard. I asked him if he would argue his case himself. He was ready to do it, and said the law would be struck down by the evening. He felt, rather innocently, that since his case was to be heard by two progressive judges, they would definitely strike the MISA down. I cautioned him that what would be struck down was not the law but his writ petition. ‘Your assessment of persons, judges and the court are erroneous. It matters little whose bench it is. Striking down the law is something that will not happen,’ I said to him. To take a decision of that kind, one needs extraordinary courage, and a very high ethical standard. That is rare in our country. The next day Yagna Narayana’s writ petition was struck down. Progressive judges, without a thought, dismissed writ

petitions of detenus from the Jamaat-e-Islami and the RSS. The question that was

decided in these cases was: ‘Whom is the right to free speech for?’ Not ‘why a right

to free speech’.

Ranga Reddy of the Jana Sangh told me a very interesting story. Naxalite leader Neelam Ramachandraiah was arrested and shot dead by the police in November 1975. The police fabricated a story of an encounter. Since Neelam Ramachandraiah had earlier been a member of the legislative council, the leader of the assembly, Chief Minister Jalagam Vengal Rao, proposed a condolence resolution. Ranga Reddy objected: ‘You ordered his killing, and you are proposing a condolence?’

Also read: Mussoorie’s deforestation was shocking. Officials tried to hide it on Indira Gandhi’s visit

The derogation of due process

In arguing about how arrests did not follow due process, I always stressed on the ways in which they derogated constitutional guarantees. However, even the Supreme Court ruled that in the matter of the deprivation of personal liberty, no basic feature of the Constitution was violated. The same court that ruled that in the matter of property there could be no law that altered the basic structure of the Constitution also ruled that personal liberty cannot be interpreted with reference to the basic structure doctrine. The basis of this interpretation was that since it is the state and the Constitution that confer rights, the same may be withdrawn. I am of the opinion that it is a grave error to interpret fundamental rights in this manner—any ruler, state, government or Constitution only confirms, respects and guarantees protection of the inherent rights of persons. Let us take the social contract theory in political philosophy. People enter into a conditional contract to vest certain authority in the ruler and government. A feminist philosopher has persuasively argued that the social contract is in fact a contract between men. This is an argument I agree with.

With the Emergency, even the welfare provisions of the Constitution were adversely affected. The Emergency case came up in the Supreme Court. Even when I argued a case in the Andhra Pradesh High Court before a full bench, Justice Ramachandra Reddy said, ‘If you file a petition that the police have shot and killed a boy in the street, it is not possible to admit it.’ The attorney general of India, Niren De, said the same thing to Justice H.R. Khanna in the Supreme Court—that the right to life could be suspended during the Emergency. Justice Bhagwati was also on that bench. One judge wrote that the government was looking after detenus like a mother looked after her children. Justice Y.V. Chandrachud said that he had ‘lofty faith’ in the government. The Andhra Pradesh High Court full bench passed a judgment supporting the Emergency. Even today, I am surprised when I read that judgment. If we look at Article 51A, which sets out the Fundamental Duties that purportedly derive from the values of the freedom struggle, these are values that apply uniformly to all: to the chief justice, to me and to the chief justice’s stenographer. Justice H.R. Khanna was the lone dissenter who took a very principled stand on the Emergency and resigned. I have not come across another judge like him. In Andhra Pradesh, the court ruled in favour of preventive detention. The Supreme Court also cited the Andhra Pradesh decision favourably. Justice Bhagwati was part of this.

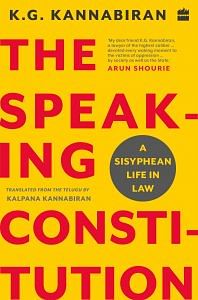

This excerpt from K.G. Kannabiran’s The Speaking Constitution, translated by Kalapana Kannabiran, has been published with permission from Harper Collins.

This excerpt from K.G. Kannabiran’s The Speaking Constitution, translated by Kalapana Kannabiran, has been published with permission from Harper Collins.