15 December 1971

On this day, the end of the war was already in sight, but by no means certain. This is always a difficult period in wartime; nobody wants to be potentially the last man to die in any conflict, and good soldierly leadership is crucial, at junior commander levels particularly, to prevent understandable hesitancy from setting in.

The previous night, the night of 14/15 December, elements of the Pakistan Army remaining in Dacca moved out of their quarters in Dacca Cantonment and into buildings of Dacca University, inside the town. Several squadrons, including 28 Squadron, were tasked to flush them out from the air, in an operation code-named Operation Street-Fighting. The name was (probably intentionally) ironic; the operation was specifically intended to spare the Indian Army from having to undertake house-to-house street fighting.

From the morning of 15 December, IAF squadrons mounted multiple missions. Dacca University was in the middle of the city and had tall buildings around it. IAF pilots actually flew right between the taller buildings, going in at such low altitudes they were often below the topmost floors. Wing Commander Bishnoi wrote, again: ‘It was a great experience flying at 1000 km/h thru these narrow corridors and having people actually looking down at us from the windows above … We made two passes each and struck hard, delivering rockets without compliments to the Pakistani Army housed there. A total of 1,280 57 mm rockets were fired into Dacca University buildings by the “First Supersonics” on that day.’

In addition to Wing Commander Bishnoi’s 28 Squadron, a total of forty sorties were mounted by the Indian Air Force, against Pakistani troops holed up in the university buildings. By the evening of the fifteenth, the top brass of the Pakistan Army had abandoned the university and had shifted to the Intercontinental Hotel, the most prominent hotel in the city at the time, which as previously mentioned, the Government of India had declared a safe haven. It was, of course, intended for third-country nationals and other neutrals, but Pakistani senior officers and civil servants had already begun forcing their way in.

Also read: Why my Pakistani grandfather Col Ali went back to Dhaka to apologise for 1971

Indian Army troops, spearheaded by the paratroopers dropped at Tangail, were already within fifteen to twenty kilometres of Dacca. Apart from the thrusts towards Dacca from three different directions, Indian troops had also started to land in other parts of the country, including an amphibious landing by the Indian Navy at Cox’s Bazaar, in the extreme southeastern corner of Bangladesh. The landing of Indian troops here was mainly in response to reports that Pakistani troops were attempting to escape to Burma through that town.

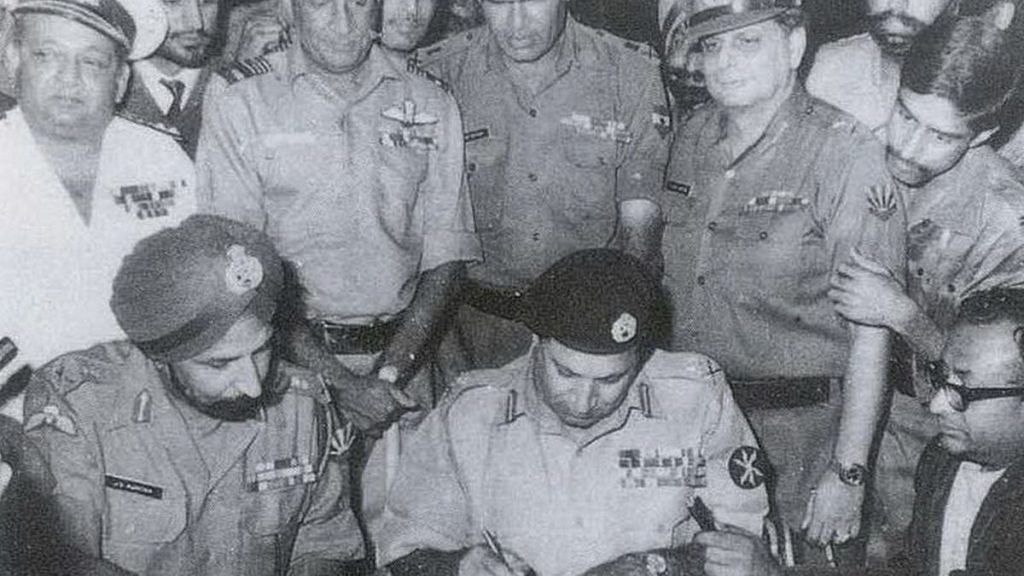

Back in Dacca, the Pakistani Army commander in East Pakistan, Lieutenant General A.A.K. Niazi, informed the US Consul General that he was willing to accept a ceasefire and transfer of power. Again, he attempted to represent this as a ceasefire and a safe conduct for Pakistani forces and their supporters, rather than as surrender.

This ceasefire offer was passed to Washington, and then relayed to New Delhi by the US government through its embassy in New Delhi. In reply, the Indian government rejected the conditional ceasefire, and reiterated the demand for ‘the unconditional surrender of all forces in East Pakistan’. This was a bold but calculated move; there was already mounting pressure on India on the floor of the UN to stop fighting, and its military and civilian leadership were only too conscious that if it agreed to a ceasefire rather than a surrender, there was every prospect that the military victory would be frittered away in political negotiations.

Also read: Operation Eagle — The 1971 mission by RAW and Tibetan SFF that has no official record

The Indian Army chief, General Sam Manekshaw, continued to broadcast radio messages addressed to Lieutenant General Niazi, setting out terms to stop the fighting and surrender to Indian troops. His broadcast warned that he knew of escape plans by senior Pakistani officials and named the ships and aircraft that had been earmarked for escape, demonstrating the completeness of the intelligence he possessed.

He promised that following surrender, all uniformed Pakistani personnel would be treated in accordance with the Geneva Convention, including provision of medical treatment to the sick and wounded and burial for the dead. In point of fact, the Indian Army was already doing this; Pakistani troops had been leaving behind their dead and wounded while falling back, and the Indian Army was already taking care of substantial numbers of Pakistani wounded and dead.