Nehru was only shown Plan Balkan before he went to bed that night. What he read horrified him. According to Plan Balkan, India would not be partitioned into two countries but vivisected in to dozens of countries; each province would have the right to secede; each Princely State the right to become independent.

At about midnight, Krishna Menon’s bedroom door burst open to admit Nehru, beside himself with rage and consternation. Menon was kept up until four o’clock that morning, while a distraught Nehru paced the floor, tearing the document verbally to shreds. But why, asks Philip Zeigler, was it ever imagined that Nehru would ever accept the original plan, when the new one gave him so much angst? There are so many versions of the story that the truth remains in question even today.

In Zeigler’s telling of the tale, VP’s role is so minimal as to be expunged altogether. The credit is given, instead, to Mountbatten’s resilient nature, which saw him shedding “only a most cursory tear for all the spilt milk around him, before he settled down to seeking a new and more satisfactory solution.”

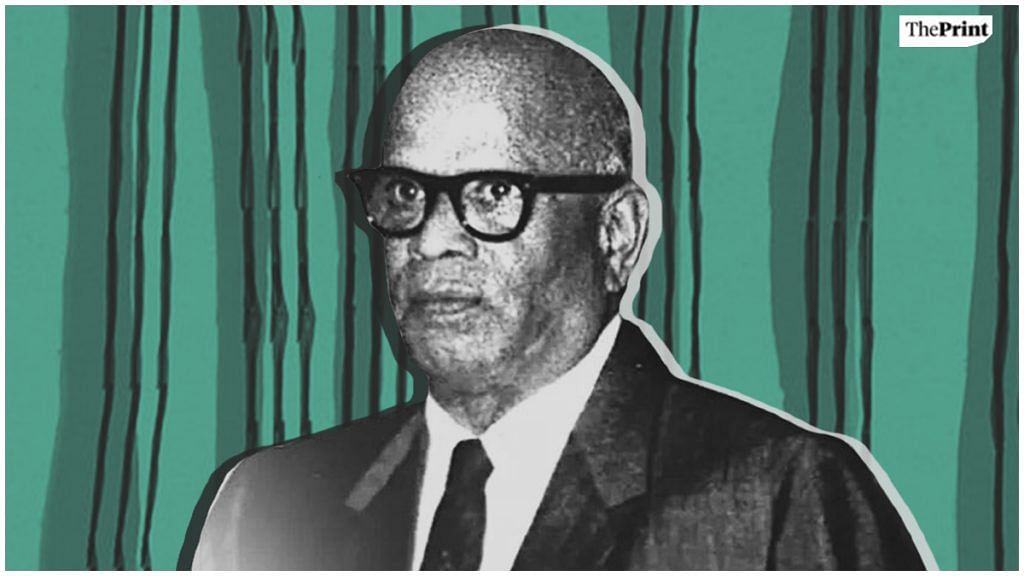

As Mountbatten’s authorised biographer, Zeigler’s account has done much to solidify a version put about by the Viceroy himself. In any interview, recording or archival source, to which he has lent either his voice or his words, Mountbatten insisted that India’s freedom could not have been gained without his “hunch”, and without coming up with an alternative Plan on his own. In the process, V.P. Menon’s part in this drama—not least of which is his role in presenting a successful alternative plan for India’s future—has been relegated to a footnote in history. The reality was very different.

Also read: The private lives of the Mountbattens — Open marriage, flings and paedophilia

In his official narrative, V.P. Menon tactfully suggests that Mountbatten showed Nehru the revised Plan Balkan because he had seen for himself the advantages of the V.P. Menon Plan. That, he suggests, was the rationale behind the “hunch”. He is not wrong. However, the Viceroy had put his Constitutional Advisor in a disastrous position. Nehru, always highly strung, had predictably lost his temper at seeing a wholly different Plan to the one that had been discussed with him just that morning. By not allowing VP to mention Plan Balkan’s existence, and by giving Nehru the wrong idea from the start, Mountbatten had trapped his Constitutional Advisor in such a position as to portray him as an untrustworthy liar. His reaction at the moment was laconically termed the “Nehru bombshell” by the Viceroy, and others, including Ismay, who referred to Jawaharlal’s reaction in vivid terms, saying that the future Prime Minister had “blown up” in fury. Mountbatten received an incendiary missive from Nehru on the morning of 11 May.

The Balkan Plan was frightening in its implications for India, wrote Nehru. “The present proposals virtually scrap the Constituent Assembly … and deprive the Assembly of its essential character …” he wrote.

Having dispatched this to Mountbatten to read over breakfast, Nehru sent for VP. Completely unaware that Mountbatten had showed the Prime Minister the revised version of Plan Balkan, VP arrived at Viceregal Lodge at 8 am, and was promptly blindsided by Jawaharlal, who stormed around the study.

The whole approach of this Plan was wrong, Nehru raged—how could anyone cut India to pieces like this? “How can you blame Panditji, tell me?” VP asked Hodson, years later, his voice quietly resigned. “How could he believe that his Constitutional Advisor had never seen this Plan? How could he believe that when an alternative Plan was being argued, that same Constitutional Advisor had not said a word? You tell me, Harry, what would anyone think? I had to stand there and listen to him.” When he could finally get a word in edgewise, VP tried to calm Nehru down. “But I did not know the Plan (Balkan) had been shown to him, so whatever I was saying sounded unreal. And he knew it was unreal.” VP was saved from further embarrassment only by the insistent ringing of the telephone in the hall. It was from Viceregal Lodge. Mountbatten wanted to see VP at once.

“When I got to Viceregal Lodge, Lady Mountbatten was there, in the study, holding her husband’s hand. I could see from their faces that this was disaster.” Still, Mountbatten tried to brazen it out. He wasn’t sorry he had shown the plan to Jawaharlal, he said. Imagine what would have happened had he gone ahead with the conference of 17 May anyway! The question was, how did one now retrieve this situation? “I told him, ‘Sir, you have never listened to me before, but I beg of you to please listen to me now.’”

Also read: Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel: The man who shaped India

VP repeated his Plan, modifying it according to what he had heard from both Mountbatten and Nehru. He now urged the Viceroy to think about Partition seriously, because it was the only way to ensure both the early demission of power, and as a result, obtain Congress approval. The only obstacle, as always, was Jinnah. Would he accept a mutilated version of his dream? “I reminded Lord Mountbatten that he himself had gained the impression that Jinnah was reconciled to the idea of partition of the Punjab and Bengal. Whereas the Plan approved by His Majesty’s Government would break up the country into several units, my Plan would retain the essential unity of India, while allowing those areas to secede which did not choose to remain part of it.” There was nothing else Mountbatten could do, at least not in the face of the stingingly eloquent letter Nehru had just sent him. Nehru was summoned for a mid-morning meeting, to which he arrived, still protesting violently. Mountbatten heard him out patiently, then signalled to VP.

“We explained to him how our new Plan would meet his objections,” VP remembered. “But I could not tell him that Sardar approved of the bulk of it—especially Partition—because Panditji might have thought that I was hiding things from him.” Nehru listened suspiciously, but at last commented that though it sounded fine to him, he couldn’t commit his colleagues to the Plan without their approval. However, he said, he wanted to see it in writing. All right, Mountbatten said, a draft would be ready for him to see by 6 pm. It was at this point that a qualm struck VP.

It was already lunchtime—1.30 pm or thereabouts, he would recall. Nehru was leaving for Delhi at 7 pm that very evening. That left VP with precisely four hours in which to produce a draft compelling and comprehensive enough to determine the future of India, and to change the history of South Asia forever. “I know people have said of me that VP always had the Plan ready,” he told Hodson, years later. “But at that time, what did I have? I had nothing. I had a few notes and some essential points scribbled on some sheets of paper.” VP had worked under immense pressure before, but this was something else. India’s political future had been decided in a matter of three hectic hours, between 7 am and 10.30 am that morning. “But to put it in writing, Harry—that is another task all together!”

Also read: Nehru was pursuing a Kashmir solution with Pakistani support, but Cold War came in the way

VP collared C. Ganesan, his friend and stenographer and disappeared in the direction of Government House. He had not yet eaten breakfast; he didn’t have time to think of lunch. He also forgot his wife. Kanakam had come up to Simla as well, and was staying with him at Government House. These were days in which hatemail used to arrive for VP. He never spoke of their contents, and merely dismissed what must have been death-threats as “threatening” letters. None of them survive, and must certainly have been destroyed by him on the spot. However, it is likely that Kanakam felt that it was necessary to keep an eye on “Menokie” as she affectionately called her husband. She preferred that he inform her of any changes in his schedule or his whereabouts, which he invariably did. More than that, VP was beginning to suffer from a slight but persistent cough and Kanakam kept a stern eye on his daily routine. She took care of his lunches, and if he was working late at office, a tiffin would always be delivered, along with a little note to remind him to take his medications. She also knew of the letters, though she took them in her stride and in his absence, quite equably opened, read and disposed of them as she thought fit. With the chaos of the morning, though, VP had forgotten—for the first time—to call Kanakam to let her know that he had been held up at work.

By the time he reached home, armed with packets of cigarettes and accompanied by Ganesan, Kanakam was, as VP politely called it, in “a great huff.” “I didn’t know whether to pacify her, or to sit down and write this draft.” Would he like to eat? inquired Kanakam frostily. “I said I couldn’t eat, I was not hungry.” Fine, his wife retorted, if he was not going to eat, she wouldn’t eat either. “And then she went into her room and went to sleep.” However, there was no time to waste worrying about Kanakam’s temper. VP sat down and began dictating from his notes. By 6o’clock that evening, he had chain-smoked his way through nearly every packet of cigarettes he had bought, he had a splitting migraine and he was nearly faint with hunger and exhaustion. However, in his hand, VP held a draft—the first official draft of the terms of India’s independence, and of the future of South Asia: the Menon Plan. There was no time to think of the enormity of what he had done. All he could think, as he stood there, was that “it read passably well, except for the grammar.”

Later that evening, an exhausted VP took himself and Kanakam up to Viceregal Lodge to dine with the Mountbattens. The viceregal couple were in an ebullient mood—Mountbatten was laughing and had regained his buoyancy and Edwina swept in and kissed the reticent Kanakam on both cheeks. “The first thing he said to me was, ‘VP, Nehru has accepted this plan, subject of course, to the acceptance of the Working Committee, his colleagues and so on.’” This was excellent news, but VP needed, as he always did, the Sardar to sign off on it.