We were traveling out to the small town of Tus, Ali went on, because it was there that Ferdowsi was buried. Jalaludin Rumi might be famous across the West; his verses about giving himself up to the “Beloved” and flinging away holy books lent themselves perfectly to secular distortion. But it was Ferdowsi who had, in the eleventh century, given the entire culture an identity and a voice.

His sixty- thousand- couplet epic, the Shahnameh, which those in the West called The Book of Kings, had hymned a new Farsi into being, over the thirty years it took to complete, much as Shakespeare had sent more than fifteen hundred words and phrases into modern English. We drew up at last at a marble edifice, at the far end of a quiet, formal garden in which couples dressed as for a restaurant in Paris were strolling around and posing for photos. We stepped into the chamber where the poet was buried, and Ali pointed out scenes from the epic poem rendered along the walls in friezes, while two romancing lovers pored over verses that warned of the capricious ways of Fate. Then our driver slipped into the space behind us.

He walked up to the sepulcher in which Ferdowsi’s body was said to rest, and placed his hand on the cold stone. He took off his baseball cap and set it against his heart. Without preamble, in a rich and sonorous baritone, he proceeded to deliver a long sequence of verses from the poem that turns history into myth and vice versa. Everything stopped. For what seemed like minutes we stood rapt. I have made the world through a paradise of words. No one has done that but me. Huge palaces and monuments will fall into disrepair, but I have made a palace out of words that shall never fade. Through this, I have immortalized Iran. As Ali concluded his translation, the driver put on his cap once more and offered me a reassuring smile. “I didn’t know if I could sing again,” he explained, in perfect English.

Also read:

“Seven months ago I was diagnosed with cancer of the throat. My doctor advised me not to sing. But when I come here, I have to try. For Ferdowsi. For Iran.”

A paradise of words: the driver’s incantation might have been expressing the single most urgent impulse that had drawn me here. After years of travel, I’d begun to wonder what kind of paradise can ever be found in a world of unceasing conflict— and whether the very search for it might not simply aggravate our differences. And the natural place to embark upon such an inquiry— should we discard the notion of heaven entirely?— seemed to be the culture that had given us both our word for paradise and some of our most soulful images of it.

The old Iranian term “Paradaijah” had been brought into Greek by Xenophon, when he’d served as a mercenary in Persia; and for centuries Persians, as most residents of Iran were then known, had cultivated detailed and ravishing visions of paradise in their walled gardens, as emblems of— enticements towards— the higher garden that awaits the fortunate. The Magi who had traveled to Bethlehem to pay their respects to the infant Jesus were often said to have come from Iran. So, too, the very word “magic” and the notion of a star shining above an auspicious birth.

The water- softened courtyards that had bewitched me one candlelit evening in the Alhambra, the landscaped gardens depicting paradise around a marble tomb that had transfixed Hiroko and me on our honeymoon, at the Taj Mahal: all, I’d read, had been inspired by Persia. But what gave particular power to the world’s largest theocracy right now was that so many competing visions of paradise seemed to be crisscrossing every hour here, with furious intensity.

After overthrowing the Shah and his Westward- facing regime in 1979, the ayatollahs who took over maintained that paradise awaits only those who give themselves to sacrifice and self- denial. The vast space in southern Tehran known as “Zahra’s Paradise” was one of the largest cemeteries on earth— home to one and a half million dead bodies— and fast- track entry to heaven was said to be the privilege of martyrs. Yet many of Iran’s citizens were still known for the remarkably refined and sensuous versions of an earthly paradise they fashioned behind closed doors.

The turbaned clerics, as they saw it, were ruthless politicians pursuing worldly ends under the guise of religion; the only pleasures that could be enjoyed in such a system lay in romance and intoxicants, the latest luxuries from abroad. And both secular and religious souls, confoundingly, continued to turn for support to the Sufi poems that Iranian schoolchildren, to this day, learn by heart. Those mystical verses traffic in the language of the everyday— roses and nightingales and wine— if only to evoke a far deeper romance with the divine.

Turning wordlessly in circles, Islamic dervishes incarnate a truth beyond doctrine and analysis. Find a heaven within, Rumi had written— it came back to me now as Ali, the driver and I sat on a platform in the sun, munching on chicken with barberries— and you enter a garden in which “one leaf is worth more than all of Paradise.”

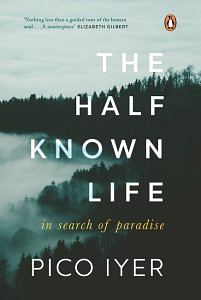

This excerpt from Pico Iyer’s ‘The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.

This excerpt from Pico Iyer’s ‘The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise’ has been published with permission from Penguin Random House India.