Nehru, whom Gandhi once affectionately called as “our Englishman” was a believer in ‘freedom at all costs’ philosophy in his younger days. He had disagreements with Gandhi when the latter insisted on the purity of both means and ends. As the freedom movement reached its goal, Nehru included Partition also as one of the costs. He tried to give a philosophical twist to it in a speech in August 1947, saying “Division is better than a union of unwilling hearts”. He also claimed that “great events were underway” and some of that greatness fell on men like him and Jinnah. So did the other leaders, the “tired old men, hungry for power”, as Ram Manohar Lohia put it.

In 1956, Nehru told Michael Brecher, his biographer, that the Congress leadership agreed to Partition because they found that as the only solution to end violence. They were also not agreeable to the Cabinet Mission Plan, which could have ensured a united India, but left the central government weak. In 1960, he confessed to British journalist Leonard Mosley that they were “tired of arguing with Jinnah and considered that Partition was most likely to be a temporary arrangement”.

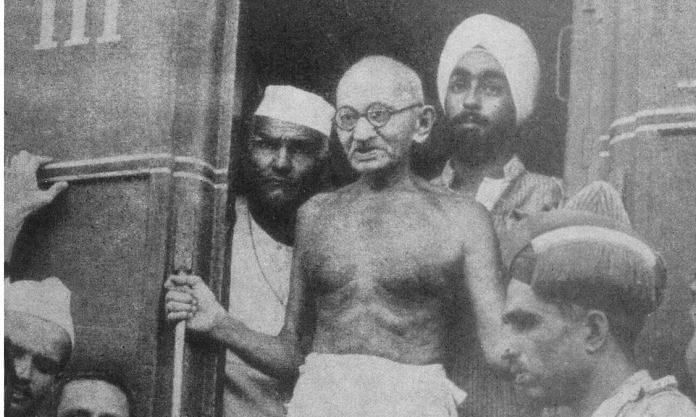

Gandhi was a shattered man when Partition was announced. “My life’s work seems to be over. I hope God will spare me further humiliation,” he bemoaned, pleading in agony, “I shall perhaps not be alive to witness it but should the evil I apprehended overtake India and her Independence be imperilled, let posterity know what agony this old soul went through thinking of it. Let it not be said that Gandhi was a party to India’s vivisection.”

Also read: ‘Gandhi did not stop here at all’—Why people in Dandi don’t say he walked that route

Gandhi may not be fully absolved of the sequence of events that had ended in the tragic Partition of the country, but it would be unfair to put the entire blame on one man who represented many lofty ideals and inspired generations. Gandhi was like a mystic and a metaphysical idealist.

During the final years of Partition, many foreign correspondents used to visit Gandhi at his Ashram in Wardha. For most of them, it was unbelievable that the great freedom movement of India was being run from that “snake-infested backwater”.

“Wardha had few charms. The water was polluted. Malaria was widespread, and the sticky, oppressive heat killed many people annually”, wrote an American journalist.

Sitting in the mud and thatch hut, “a cross between a third-rate raunch and a refugee camp” was the frail old man Gandhi, shaking up the mighty British Empire. He probably belonged to a different time and space. In 1929, Jinnah called Gandhi’s policies “utterly unsuited to modern times and the realities we have to face in India”. Those words proved more prophetic after Congress accepted the June 3rd Plan. The Congress leaders had not only rejected Gandhi’s life idea of united India but also his life ideal of moral politics.

Gandhi was a man of convictions. Once he offered to Viceroy Linlithgow that he could go and speak to Hitler. He wrote an open letter “To Every Briton” in July 1940 asking them not to fight Hitler and Mussolini and let them have what they wanted. “Britons should lie down and die as heroes of non-violence and then the war would be over”, he advised.

He gave a similar advise to the Bengali Hindus to “die fearlessly” at the hands of their neighbors without fighting back. “There will be no tears but only joy if tomorrow I get the news that all three of you (have been) killed”, he told a trio of his Bengali followers who were going to the region on a mercy mission.

Also read: ‘Not all inheritances from Partition are traumatic.’ Some stories are ‘celebrations’ too

He urged the women of Noakhali to remember “the incomparable power of Sita”. He advised them to commit suicide rather than submit to the Muslim hooligans; they should “learn how to die before a hair of their head could be injured”. They could “suffocate themselves or… bite their tongues to end their lives”. If such methods were difficult, they should drink poison, he advised. “His idea was not an idle idea. He meant all he said”, reads Gandhi’s own transcript of his comments.

His Saint-like innocence was misunderstood by many and many found inconsistency in his words and deeds. But Gandhi had his explanation for that. “My aim is not to be consistent with my previous statements on a given question, but to be consistent with truth as it may present itself to me at a given moment. The result is that I have grown from truth to truth”, he confessed.

Gandhi was an enigma to many in his life time. He continues to evoke strong sentiments and resentment even to this day. His Bhakts elevate him to a super human moral pedestal while his critics evaluate him from a contemporary religio-political lens. Gandhi probably lived somewhere in between these two levels.

“More than anything, though, my fascination with India had to do with Mahatma Gandhi. Along with (Abraham) Lincoln, (Martin Luther) King and (Nelson) Mandela, Gandhi had profoundly influenced my thinking. As a young man, I’d studied his writings and found him giving voice to some of my deepest instincts,” former US President Barak Obama stated in his memoir, A Promised Land. “His notion of ‘satyagraha’, or devotion to truth, and the power of non-violent resistance to stir the conscience; his insistence on our common humanity and the essential oneness of all religions; and his belief in every society’s obligation, through its political, economic and social arrangements, to recognise the equal worth and dignity of all people – each of these ideas resonated with me. Gandhi’s actions had stirred me even more than his words; he’d put his beliefs to the test by risking his life, going to prison, and throwing himself fully into the struggles of his people,” he wrote.

M.S. Golwalkar, the Sarsanghachalak of the RSS, who was wrongfully imprisoned by the Nehru government after Gandhi’s murder, said in 1949, “If Gandhism is ‘reactionary’ in that it wants to revive the highest human values, we have no objection to be bracketed with Gandhiji as ‘reactionaries’.”

Probably India did not deserve a Gandhi at that time. He was perhaps ahead of his times. Gokhale, whom Gandhi declared as his ‘political guru’ in 1915, was right in describing Gandhi on different occasions as “Indomitable…, made of the stuff of which great heroes and martyrs are made, immortal, a more exalted spirit has never moved on this earth”.

This excerpt from ‘Partitioned Freedom’ by Ram Madhav has been published with permission from Prabhat Prakashan Pvt Ltd.

This excerpt from ‘Partitioned Freedom’ by Ram Madhav has been published with permission from Prabhat Prakashan Pvt Ltd.