In August 1965, having tasted blood in Kutch, the Pakistan Army sent in thousands of soldiers in twos and threes into Kashmir, expecting to wrest it from India through guile. The soldiers were dressed in civvies (in fact, in pherans). Pakistan had assumed that the people of Kashmir would help the infiltrators launch a popular uprising against ‘Indian rule’. The plan, named Operation Gibraltar, failed spectacularly because the local people, far from helping them, helped the Indian Army to locate and capture the infiltrators.

Moreover, to Pakistan’s shock, the Indian troops crossed the ceasefire line and captured the Haji Pir Pass, through which the Pakistan Army had been sending the infiltrators. Panic ensued as the Pakistanis wondered whether the Indian forces would advance further, try to take Muzaffarabad, or even attempt to take back the entire chunk of territory in Jammu and Kashmir that Pakistan had seized in 1947. Pakistani troops, so full of bravado when they start their mischief, quickly panic when they meet their match, as they did at Haji Pir and would do so repeatedly in 1965 and 1971.

To relieve pressure on their forces in Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir (POK), the Pakistan Army launched an all-out attack on 1 September against the Indian forces in the Chhamb–Jaurian region. The aim of Operation Grand Slam was to capture the Akhnoor bridge that straddled the fastflowing river Chenab. I had served in that area before and knew it well. Seizing the Akhnoor bridge would lead to cutting off the many Indian Army formations stationed in western Jammu and Kashmir. Furthermore, after capturing the Akhnoor bridge, the Pakistani forces would almost certainly move toward Jammu and cut off the Srinagar–Jammu highway. Their artillery fire would make any Indian movement on this road impossible. We would be able to get through only in small numbers, moving at night. The Kashmir valley as well as Ladakh would, for all practical purposes, be cut off from Jammu and the rest of India.

Also read: How India beat Pakistan to gain control of the world’s highest battlefield 34 years ago

The Pakistani attack in the Chhamb–Jaurian sector came as a surprise to us, for Pakistan had not declared war—even though Operation Gibraltar was akin to waging war upon us. But that could be, and was, denied by the Pakistanis, because its men were dressed in civvies and could therefore be, and were, portrayed as locals. Inexplicably, however, when the Pakistanis were close to capturing the bridge with their overwhelming superiority in numbers and firepower, they changed their commander and delayed their advance by twenty-four hours. (Their new commander was General Yahya Khan, who would later become the president of Pakistan.)

The delay and the resultant confusion among the Pakistani officers gave the Indian Army the time it needed to rush reinforcements to Akhnoor. By the time the Pakistani troops resumed the attack, it was too late. The Indian troops held on to Akhnoor, tenaciously at first, but with increasing confidence with every passing day.

It was there that we were asked, after we had failed to capture and hold on to the Ichhogil bridgeheads, to take up a defensive position at Asal Uttar.

The first to face the rolling, rumbling Pakistani Goliath comprising a hundred Pattons (among other tanks) were 1/9 Gurkha Rifles which, having none of the material needed to prepare their defences nor weapons with which to take on the Pattons, were swept aside. Also swept aside was the front battalion of 62 Mountain Brigade. 4 Mountain Division was equipped to fight in the Himalayas, not in the plains of Punjab, and so had only light weapons that were of little use against heavy armour. Even if they had heavier weapons, those would have been of little use to them. They had not received training to handle them.

Expecting the war, the army HQ had ordered the reversion of all instructors to their respective units only two or three weeks earlier, so the unit firing teams were ready. They only needed the right equipment, which was procured for them on the evening of 7 September, barely hours before the Pakistani attack began. The crews were subjected quickly to practice drills so that their actions became second nature to them. They knew that often in war you get only one chance to fire. If you don’t seize the chance, you die. Though greatly under-strength, the 4 Grenadiers were ready for battle.

Also read: This day 50 years ago, an incident along India-Pakistan border proved Partition’s futility

We too had deployed tanks of various makes at several places all over the front, including on our flanks. While we knew that the Pattons were coming, we had no idea of exactly when to expect them. The brigade commander had impressed upon the troops that there could be a lot of confusion because of the dust and smoke, and that the identification of the tanks would be difficult. It was imperative that they fired only when they were 100 per cent certain that the tanks they were targeting belonged to the enemy. If they had any doubt, they must desist from firing. Under these instructions, the troops waited with bated breath until the last moment, which meant that they fired at very close range. That not only took the enemy by surprise—they were expecting the dhoti-clad, ‘demoralised’ Indians to have fled from the area—but also made for more effective and deadly targeting.

Our other troops were also in highly vulnerable positions—especially the 4 Mountain Division HQ behind a fork a little ahead of Valtoha, our brigade with one battalion on the western road, and 62 Mountain Brigade with one battalion on the eastern road. Major (later major general) Yati Pratap of the 1st JSW course, who was then sparrow, neighbouring brigade, understood my predicament as an officer on ‘temporary duty’, and gave me all the support and advice I needed.

The Pakistanis, having probed the fields on our flanks and realising that they would not be able to make much progress there because of tall sugarcane crops, decided to try the direct road-axis, expecting that we would reveal our locations by firing at their tanks from a long distance (which would be the normal reaction of defenders).

But what happened that day was otherwise. A troop of four Pattons advanced along the road in a single file, unaware of our exact location. The tanks indulged in some long-range firing, which caused no damage to our troops or equipment. Well-dug-in, 4 Grenadiers held back their fire until our troops were sure that they were indeed enemy tanks, and felt confident that they were well within the desired range. Then they opened fire, getting the first tank. Jubilation! More jubilation followed quickly. For the tanks continued to advance, as if unable to stop. The second and the third tanks were also knocked out. The crews of the tanks pushed open their hatches to escape—including those in the fourth tank, which had not been hit at all and was therefore in almost brand-new condition. This pattern was repeated several times: The Pakistani tanks kept advancing down the road in fours, the Grenadiers got some of them with their 106 mm recoilless guns and artillery fire, and the tank crews kept running away.

Also read: Kargil shows Pakistan’s magnificent obsession of getting even with India

All of a sudden, there was a lull in the fighting. There were no more tanks. Had they called it a day? We watched the road. A squadron of 3 Cavalry joined us that afternoon, and waited too. The Pakistanis made one more attempt and failed. We waited for them to return. They did not.

Later, the commander and I went over to the ‘invincible’ Pattons to take a look at them. Quite a few of them had been damaged and abandoned. Our boys brought out of the tanks some radio equipment along with instruction books still wrapped in polythene bags, unopened. I forwarded the documents to the regimental HQ the same night.

After eating some food, we curled up in the trenches, sans blankets or mattresses, elbows under our heads, to snatch a few hours of sleep. I was dead tired, but it took me some time to fall asleep. My mind was agitated, remembering odd events from the crowded day and wondering about what the morrow might bring. That the Pattons were going to return was certain. Would they return at the same time as today, after breakfast? Might they come earlier, say, just before dawn, when we would be at our most vulnerable? Couldn’t they return earlier still, during the night? They had nightvision, after all. We did not. We would be like sitting ducks for them if they came in the night.

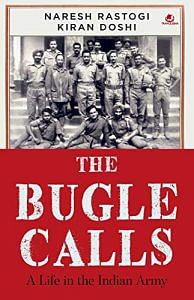

This excerpt from The Bugle Calls: A Life in the Indian Army by Lt Col Naresh Rastogi (retd) and Kiran Doshi has been published with permission from Westland Publications.